Project Description

13. Sayı

Mural

DİPLOMAT – KASIM 2005

13. Sayı

Diplomat

Kasım 2005

DIPLOMAT IS one year old.

The first edition of DIPLOMAT came out in November 2004. Now it is 2005. During this period, eighteen ambassadors and two resident representatives of international organizations have agreed to give interviews or contribute articles. Meanwhile, the magazine has proved its quality and trustworthiness. Well satisfied with these results, the DIPLOMAT team is now working with greater motivation than ever to enrich the content of future editions.

The subject of our interview this month is Georgian Ambassador Grigoi MGAL0BLISHVIL1, one of Ankara’s youngest ambassadors. The ambassador speaks of the reforms which have been carried out in his country in the last year. He also dwells on relations between Georgia and its neighbour Turkey, including of course, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline. The pipeline is itself the topic of our ‘Speaking Out’ section, which was contributed by Mr. David Winter, BTC Project Manager Turkey.

The embassies established in Ankara in the early years of the Republic are today among the most pleasant parts of the city. One such embassy is the Embassy of Poland, situated right opposite Kugulu Park in the Kavakhdere district. We are sure you will read our article about the building and its grounds with interest.

Turning to art, we feature a sculptress for the first time. Known for her abstract works, Vildan ÇETiNTA§ is at the same time an academic at Gazi University. A separate article focuses on the recently-opened Ministry of Foreign Affairs Art Gallery. The MFA has undertaken a pioneering role within the Turkish bureaucracy in fostering interest in the arts by opening a gallery on its premises. A new exhibition opens every month, and we strongly recommend foreign diplomats visiting the Ministry on business not to leave without taking a look,

The New Year is approaching, and we will all soon be-exchanging Christmas and New; Year cards. Why not send handsome UNICEF cards – and lend a helping hand?

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Interview

Ambassador Grigol Mgaloblishvili: More projects to come

By Bernard KENNEDY

At 32, Ambassador Grigol Mgaloblishvili of Georgia is one of Ankara’s youngest ambassadors but also one of those who are most familiar with Turkey. He first came to Istanbul as an exchange student and later worked in the capital as an interpreter. Joining the Foreign Ministry in 1995, he visited Ankara several times and took diplomatic courses at the Middle East Technical University. Between 1998 and 2001, he successively held the posts of first secretary and counsellor at the Georgian Embassy here. After further study in Oxford, he rose to become director of the Europe and EU Integration Department at the Ministry in Tbilisi. He was appointed ambassador in 2004, in the wake of momentous events in his home country. Those events, Georgia’s relations with Turkey and its other neighbours and, of course, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline project, were among the main themes of our interview.

Q We are approaching the second anniversary of the Rose Revolution on November 23. In what ways has Georgia changed for the better?

A There have been so many changes; it’s impossible to list them all. Corruption has gone down significantly. We have simplified tax procedures and cut the number of taxes. Customs is working much more efficiently. In order to tackle the root causes of corruption, the bureaucracy has been downsized but the salaries of public servants have been raised 6-8 times. As a result, state institutions function more efficiently. Police officers are getting salaries of about US$400 a month, which is ten times what they were receiving before. At the same time, we have eliminated checkpoints. With the change of regime, the budget tripled instantly from 1.2bn lari to over 3bn lari. The increase in the budget is in itself a sign of how much of the Georgian economy was in shadow and how much the administration has improved. We are also working on reforms in education, the judiciary, local government…

Q How has the economy performed?

A GDP growth was nearly 7% in 2004. We have kept inflation well within single digits even though the budget has tripled – and despite the large cash inflow because of the privatisation process. The most visible change has been the huge infrastructure works which have been taking place all over the country during the past year. No infrastructure work had been done for fifteen years. Today, visitors to Tbilisi say they cannot recognise it any more. In addition to our own resources, the US is to provide almost US$300m for rehabilitating regional infrastructure and promoting private sector development through the Millenium Challenge Corporation. Turkish companies are among those involved in infrastructure works. To give an example, TAV is constructing two new international airports in Tbilisi and Batumi. We also signed an energy barter accord with Turkey just a few months ago.

Q What about politics?

A The main test for new democracies or countries going through transitional periods is elections. Since the Presidential elections in early 2004, we have also held general and by-elections in the Parliament. All these elections have been evaluated as fair and transparent by all international observers, including Organisation for Security and Organisation in Europe and other institutions. Rigged elections have become a thing of the past.

Q How much have the changes affected the Foreign Ministry?

A The whole system has changed, and this is reflected in the foreign service too. In general, a relatively younger generation took over the running of the country – people with more credibility and perhaps a better education. In the Foreign Ministry, career diplomats now have more opportunities for promotion.

Q What does the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline mean for Georgia?

A This is an extremely important project not just for Georgia or the participating countries but for the whole of Europe. It has been a great success thanks to the efforts of the participating countries and the oil companies as well as outside support. When I was in Turkey before, I heard a lot of pessimistic statements to the effect that the project was just political and did not make economic sense. But with today’s oil prices you don’t need to be an expert to realise that it has an extremely important economic dimension as well.

Georgia will receive revenues of US$60-70m per year in transit fees, or US$2bn during the lifetime of the project. This is from Azeri oil alone, and we are now also receiving very positive signals from Kazakhstan. Meanwhile, the construction work has also created side-benefits such as employment and business opportunities. Much more importantly, the pipeline means a diversification of energy routes, an improvement in energy security, the development of regional cooperation and a new place on the world map.

Q This is not the only infrastructure project involving Georgia and Turkey, is it?

A Many projects which have been discussed for a long time are now starting to be implemented. We believe that we can complete the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline by the end of the next year, to deliver Shah Deniz Gas to Erzurum. This too is crucial for energy diversification of supply because now we have only one supplier. Feasibility studies for the Kars-Tbilisi or Kars-Baku railroad are being conducted with funds allocated by the Turkish government. There have been two trilateral ministerial meetings, and there is a big potential for Kazakhstan to join as well. As has been proved in the case of Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan, we think this will be not just a political project but also an economically viable one. We are discussing opening a new border gate and modernising the Sarp border gate. Another very important issue is the joint use of Batumi Airport for neighbouring regions of Turkey. A fibre-optic cable connection is about to start operating.

Q Are there any improvements in trade between the two countries?

A We have always had very good political relations with Turkey but security considerations and corruption made it difficult for Turkish companies to enter the Georgian market. Now it takes only 3-4 minutes to cross the border through the new “green corridor”. During the last six months we have had no complaints of delays from transporters crossing Georgia from Turkey. As of the beginning of next year, the prime ministers of the two countries have announced that citizens of the two countries will be able to travel to one another’s territory for 90 days without having to obtain a visa. Next year, the Black Sea road will shorten the journey from Trabzon to Batumi to just one-and-a-half hours. All these things will benefit trade. We are contemplating a bilateral trade volume of US$2bn within three years. There are still a lot of things to be done to liberalise our trade relations. We are working intensively towards a free trade agreement or a preferential trade agreement, and an agreement on the avoidance of double taxation. We hope that we will be able to sign both of these agreements by the end of this year, for the benefit of business people and all our citizens.

Q What are you selling to Turkey?

A We are selling goods like fertilisers, chemicals, wood products and iron and steel. But we are especially focusing on agriculture. Most of the agricultural products in Georgia are organic and we believe that they can compete in any market. Among processed agricultural products, wine is a major item. Georgian wine is not just a simple commodity but a part of our national identity. We believe that it will gain its place in the Turkish market, especially if we take into consideration the increase in tourists coming to Turkey from CIS countries – Georgian wine is one of the most popular in this area.

Q What is the state of cultural relations between Georgia and Turkey?

A During the Soviet period the doors between the two states were locked for almost 70 years. This was followed by a period of turmoil. By developing our cultural relations we are getting to know each other as neighbouring countries should. There is great potential. We share the same geography and have a common cultural heritage as well. There are a lot of significant Georgian monuments in Turkey and a lot of Ottoman monuments in Georgia. We have recently just started to cooperate to take care of these historical moments. This will help us to publicise our cultural connections not just in Turkey and Georgia but worldwide. We have a rich mutual agenda of festivals and exhibitions in the two countries. We frequently hold exhibitions at our embassy as well. As part of our efforts to introduce Georgia’s rich, unique culture to Turkey we have opened free Georgian language courses within the Embassy and the numbers of people who applied was well beyond our expectations.

Q Are there any problems in your relations with Turkey?

A No, we have no political difficulties. Although we are neighbours and it’s not an easy region, Turkey and Georgia have set a good example of how relatively smaller and larger countries can cooperate in a very constructive way.

Q What about your relations with other neighbouring countries?

A It’s a part of our foreign policy to have good, constructive relations with all our neighbours without any exception. We are doing our best. We have strategic cooperation and very close relations with Azerbaijan. We have good, constructive, very beneficial partnership with Armenia. We are taking steps to normalise our relations with Russia. Firstly, we now have a clear timetable that by the end of 2008 there will be no Russian military bases in Georgia. This is not just the will of current administration, but the political will of Georgian nation. Secondly, we are aiming to elaborate the expediency of the sole presence of Russian peace-keepers and make the Russian involvement more constructive than it is today, in order to solve frozen conflicts more efficiently. Our Parliament has just adopted a resolution concerning the CIS peace-keeping forces to the effect that if Georgia does not see any progress or if peace-keepers do not function in an effective way our parliament will ask our executive bodies to start negotiations on ending the peace-keeping mission. I am sure that a strong, united prosperous Georgia will benefit Russia much more than a Georgia which has unresolved conflicts on its soil, so we expect the Russia side to be more constructive in the conflict resolution process because both sides will benefit. This is not a new idea. President Saakashvili said in his inaugural speech that we should forget all of those old disputes and start our relations from a new page.

Q But you also have US forces on your territory…

A No. We have some training programmes. We had a very successful train-and-equip programme for three years. Now we have started a new phase. US instructors are training our military forces. Both the US and Turkey are assisting Georgia in building up its armed forces. When one neighbouring country assists another neighbouring country in building up its armed forces, it means that there is full trust between the two states. Likewise, if the US is training our forces to NATO standards, this shows that the US wants to see a strong, stable, democratic Georgia, within the Euro-Atlantic structures of security.

Georgia is a small state, but it is contributing significantly to international peace-keeping operations such as Afghanistan, Kosovo and Iraq. International terrorism is a threat to all of us and when any area becomes a breeding ground for international terrorism all parties should be united and tackle this problem. I should add that the same applies to Abkhazia and southern Ossetia too, because they are just criminal enclaves and it’s very easy for them to become centres for smuggling drugs and weapons and other kinds of trafficking and all kind of illegal activity. So these uncontrolled territories are not just an internal problem of Georgia but it has a negative effect on the whole region – and the effects may reach beyond the region. All parties should work together to overcome this problem. Above all, all states and political groups should avoid double standards when they approach such sensitive issues.

Q Where do you stand on the Karabakh dispute?

A We are for the stability of the southern Caucasus. We support the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Azerbaijan. This approach is the main pillar of our relations with any other state. At the same time we are for the peaceful resolution of all conflicts.

Human angle

Humanism and the economic order

by Prof. Dr. Özer OZANKAYA

The root cause of the complicated situation to which humanity is exposed today is the insistence on continuing to implement capitalism as the sovereign order, if necessary by force, even though it is outdated.

The years since the weakening and collapse of the Soviet Union have shown that the failure of socialism does not mean the victory of capitalism. In a one-polar world atmosphere, the military and political power of the political West, driven by the monopolist capitalist classes, continues to divide peoples and provoke local and civil conflicts, and even to occupy whole countries in order to seize their natural resources. Nations are scattered, poverty spreads, people are killed en masse or deprived of their homelands. Iraq is the most evident and ugliest example. With the exception of a limited “white” population, four-fifths of humanity is caught up in these whirlpools.

Yet at times when the nations of the Western countries have faced world economic crisis or the competition of the communist block, or have fallen into internal social-justice conflicts resembling internal wars among themselves, the elite statesmen to whom they have turned for salvation have themselves been harshly critical of capitalism, speaking of the necessity to reform it, and bringing about changes that have taken concrete form in the concept of the welfare state.

Churchill’s appeal

By forgetting the past, nobody can be dignified or free, either today or in the future. Nobody can prepare for what is to come by ignoring history. It is therefore very beneficial to remember the words of Winston Churchill – a deeply conservative statesman – when describing the situation into which capitalism dragged England in the 1920s. This article will also recall the words of another highly conservative politician, General De Gaulle, explaining how capitalism channelled France towards the brink of civil war, the observations of the renowned American sociologist Robert L. Heilbroner and the evaluations made by a group of economists from Cambridge University.

Criticising the Conservative Party, from which he temporarily resigned, Churchill argued that:

“The Conservative Party is a party of great vested interests bounded together in a formidable confederation: corruption at home, aggression to cover it up abroad; the trickery of tariff juggleries, the tyranny of a party machine; sentiment by the basketful, patriotism by the imperial points; dear food for the millions, cheap labor for the millionaire… The greatest damage to the British Empire and the British people are not to be found among the enormous fleets and the Armies of the European continent. Nor in the solemn problems of Hindustan. It is not the yellow peril nor the black peril. No, it is here in our midst, close at home. Close at hand in the vast growing cities of England and Scotland and in the dwindling and cramped villages of our denuded countryside. It is there you will find the seeds of imperial ruin and decay. The unnatural gap between rich and poor; the divorce of the people from the land; the want of proper discipline and training in our youth; the exploitation of our boy-labor; the physical degeneration which seems to follow swiftly on our civilized poverty; the consequent insecurity in the means of subsistence and employment which breaks the hearts of many a sober, hard-working men; the absence of any established minimum standard of life and comfort among the workers; and at the other end, the swift increase of vulgar and joyless luxury. They are the enemies of Britain. Beware lest they shutter the foundations of her power.”

De Gaulle: Respect

In the France of the 1950s, General de Gaulle described the deep depression in his country as follows:

“One day the machine was invented and capital married her. And this couple dominated the world. Since then many people – the workers in particular – became dependent upon them. Being dependent upon the machines for their works and upon the bosses for their jobs, they feel morally degraded and materially threatened. And here is the outcome: class warfare! It is everywhere: in the workshops, in the fields, in the offices, in the streets, in the depth of eyes and hearts! It poisons human relations, terrifies governments, destroys unity of nations, causes wars. Because what lies behind the great shocks which the world has been undergoing is indeed this very social problem so often underlined but never solved. What provides the separatists in our country with such hopeless occupations is again this same social problem so often underlined but never solved. However much the free nations may oil their propaganda machine, no matter whether they arm themselves to the point of their own ruin, the sword of Damocles will hang over their heads for as long as each individual is not accorded a due place in society and the portion and dignity due to it!”

To these citations, we should add the following words of President Roosevelt, who accepted the need for the state to take on economic responsibilities in the United States of the 1930s, and gave life to the ‘New Deal’ policy: “I see one third of my nation ill-housed, ill-clad and ill-nourished!”

Scientific criticism

In the 1980s, Kirk F. Koerner of Cambridge University argued, in the introduction to a book entitled ‘Liberalism and Its Critiques’, that since the time of Machiavelli, the Western world had ceased to be oriented primarily by the endeavour to achieve wisdom and virtue and had instead come to seek after pleasure for the sake of pleasure. Values such as wisdom and virtue had ceased to be ends in themselves and been transformed into mere means at the service of happiness, pleasure and material gains, However, apart from failing to provide happiness and satisfaction, this trend had proved to be demeaning and degrading for mankind. Liberalism was the policy of politically inexperienced groups and, if fully applied, left no room for political compromise.

In the 1960s, in his book, “The Limits of American Capitalism”, American sociologist Robert L. Heilbroner argued that:

“The explosive enlargement and development of organized science and scientific technology at our time is apt to change irreversibly the capitalist social order, for they can render outmoded its basic operation mechanisms. They can cause such social problems that can only be dealt with through extra-market control mechanisms: transport, nuclear energy, drug addiction, traffic regulations, environment issues, the needs of mega-cities …necessitate increasingly direct interventions in economic sphere through common regulations and constraints. The incursion of technology has pushed the frontiers of work … into a spectrum of jobs whose common denominator is that they require public action and public funds for their initiation and support.

“When we try to imagine the implications of automation, genetic engineering, nuclear energy … the scale of these actions and controls becomes clearer. With the high welfare level reached in the developed part of the world, material needs are no more efficient stimulants for human behavior: who would wish within such conditions to be the rich man’s servant at any price? Therefore the market stimuli are no longer met readily with obedient responses.

“All efforts to raise money-making to the level of a positive virtue have failed, whereas science and its technical application is the burning idea of the twentieth century.

“The altruism of science, its ‘purity’, the awesome vistas it opens and venerable path it has followed have won from all groups that passionate interest and conviction that is so egregiously lacking to capitalism as a way of life.”

Transcending the West

The above were largely concerned with overcoming the troubles of Western societies alone. In international society, however, the dominant principle should be that “All humanity is a body and all nations are the organs of this body. If there is an illness in one of them, this will affect the whole body and prevent it from functioning in a healthy way.”

The states of the Political West have, in fact, agreed not to make wars among themselves. They have created joint political, economic, monetary, defence and security organisations and are cooperating in jointly exploiting the world and the labour of illegal and foreign workers in their own countries. In this way they have arguably alleviated their own problems. However, the rapid growth of international transportation and interaction – a basic and indispensable element of the new scientific and technologic atmosphere pointed out by Heilbroner – has not stopped. In other words, no state or society can deem itself secure and free to do whatever it wants. As the founder of the Republic of Turkey, Atatürk said: “The structures based on the captivity of the nations are dedicated to destruction everywhere.” Atatürk’s dictum “Peace at home, peace abroad” is still valid.

Atatürk cited many good examples for humanity of both the scientific and artistic dimensions of politics can be fulfilled. One of these is the implementation of the “democratic economy” principle. Thus, he proved that societies can be protected from the destructions of the fiction of the socialist doctrine envisaging a “society abstracted from the individuals” and the fiction of the capitalist doctrine foreseeing an “individual living alone”.

Argentinean Political Scientist Blanco Villalta made the same assessment when he wrote that “Atatürk… contributed a political plan which has wide possibilities for the future of man:… a political system of an economic and social character, in which the direction of the economy is the fundamental responsibility of the state which intervenes as far as is necessary and useful, and no further; and a people which is absolutely free to elect its rulers, free to adopt its own ideas, free in conscious, and possessing the right of choice.”

Arts:

Vildan Çetintaş: A life of sculpture

by Sibel DORSAN

“It is difficult to be a woman, in Turkey or in the world in general. To be a woman artist is more difficult. To be a woman sculptor is much more difficult.” These are the words of Associate Professor Vildan Çetintaş of Ankara’s Gazi University. Imperceptibly, our conversation about Çetintaş’s works and her personal inspirations was transforming itself into a survey of artistic education – and of the short history of sculpture in Turkey…

A woman for whom women are also a subject, a sculptor who might have been a painter or a teacher, were it not for fortune and the history of which she has become a part. The themes of Vildan Çetintaş’s work are universal and timeless, yet few artists can be as conscious as she of their coordinates in place and time.

Çetintaş settled in Ankara in 1980. She worked for the Culture and Tourism Ministry in the directorate of the State Painting and Sculpture Museum from 1984 to 1996. Since 1996, she has been teaching sculpture in stone, sculpture in wood, and design at the Vocational Training Faculty of Gazi University, where today she is an assistant professor. Her works have been acquired by the State Fine Arts Gallery in Adana, the Ankara Metropolitan Municipality, Selçuk University and numerous private collections.

Interviewing the artist at her home, I was curious to know what had drawn her into sculpture – an art form which in Turkey has only latterly strayed beyond the bounds of public monuments. At first, it turned out, she had aimed only to be a teacher. But one step into the exuberant world of art education was to lead to another.

The road to the Academy

“After primary and secondary school I went to the teacher training college for primary school teachers in Istanbul. My teachers there recommended the Buca Education Institute for my degree studies, which followed. I was studying to become a painting and music teacher, and at first I was more inclined to specialise in music. It was perhaps when I met Turgut Pura that my life took a different direction. He was a much-loved teacher and the first person to guide me in the direction of sculpture.”

Pura proposed that after graduating from the Institute, Çetintaş should enter the Art Academy examinations and study in the sculpture department. Although already qualified to teach, she was to take the Academy entrance examination in both painting and sculpture, coming seventeenth in painting, and third in sculpture.

The artist went on to tell me one of her abiding memories: “During the exams, the distinguished sculptor Şadi Çalık, later to become my teacher, said to the assistants: ‘That girl over there with the blue eyes. Her drawings show that she is cut out for sculpture. She must also have passed the painting exams, but make sure she doesn’t go over to painting – she must stay in our section.’”

Educational roots

Training at the academy was demanding, requiring physical and emotional strength as well as mental effort. Differing materials were not easy to master. The support and tolerance of the artist’s family helped her through. Yet today she remembers those days fondly as a “wonderful experience.” She recalls the exhibitions which they held in the forecourt of the school, which they nicknamed ‘Hergele Meydanı’ (Allcomers’ Square). Students from all departments would take part, with prizes awarded at the end. They would all exchange views concerning the various works of art.

“One person who influenced me strongly was Rudolf Edwin Belling. Belling put into place the basis of a system which has had a profound affect upon the Academy. His method is still implemented at the Academy, and it was also the theme of my PhD thesis. It is based on the principle ‘practice – and live – what you learn’.”

Rudolf Edwin Belling became the head of the sculpture department of the School of Fine Art (‘Sanayi-i Nefise’) as a result of the university reforms which became effective on May 31, 1933. Established in 1883, the school was the first institution in Turkey to provide training in sculpture. Its restructuring resulted in the theoretical and technical foundation of today’s sculpture workshops.

The Atatürk revival

Çetintaş is not slow to give Atatürk his due. The founder of the Republic, she says, “was a person who understood the social importance of art very well, to the extent that he elevated the country’s culture and art policies to the level of state policy, creating an understanding of art which was not to be changed according to the political tendencies of the various governments.”

For sculpture, this meant a revival. “The Turks have a tradition of sculpture from Central Asia, and they left traces of sculpture in all the territories they passed through on their way to Anatolia, beginning with the Orhon inscriptions which date back to the first half of the eighth century AD. The Shamanist and Buddhist Turks frequently created sculptures, but under the influence of Islam the place of sculpture came to be occupied by architectural and gravestone carving. Whereas the West used sculpture to spread Christianity, and deepen people’s attachment to it, in Islam there were for many years no three-dimensional figural carvings – in other words sculptures – because of Islam’s prohibition of pictorial representation.”

The Ottoman era produced incomparable examples of calligraphy, miniature painting, tezhip, and other kinds of book decoration and handicrafts, and above all of architecture. But sculpture only appeared in the reign of Sultan Abdülaziz, who had a sculpture of himself made, and decorated the gardens of Beylerbeyi Palace with sculptures of animals brought from France. But these works were confined to the palace, and many years were to pass before Turkish society took sculpture to heart.

Aspects of woman

Among the paintings on the walls, Vildan Çetintaş’s figurative and abstract paintings catch the eye. Around the house are beautiful sculptures spanning the whole spectrum from classical to modern, and from figurative to abstract. All are remarkable for the harmony of their carving, and the balances created by their open and closed surfaces, which contain both a simplicity and a richness of artistic interpretation.

Nature and humanity are underlying themes. “There are many clues in nature for those who know how to see,” she says, “In order to be able to see, one needs both to study well and to observe well. That is the way to reach through to the artistic forms hidden in nature.”

Her early works, like her bust of the famous Turkish painter Eşref Üren, are mostly figurative sculptures. For ‘Head of a Woman’ (Kadın Başı), she used her mother as model, ‘Reunion’ (Kavuşma) symbolizes a moment when her husband returned from abroad, and she created ‘Waiting’ (Bekleyiş) while she was pregnant. As her sculpture developed, we see works which are characterized by geometric forms and a semi-abstract figurative style, such as ‘Shepherd’ (Çoban), ‘Dancing on Ice’ (Buzda Dans) and ‘Children Playing’ (Oynayan Çocuklar). A recent Çetintaş exhibition on the theme of ‘Woman’ also included sculptures of birds.

A move towards abstraction

The female form is a theme on which the artist has worked intensely. In some of her sculptures, which present the woman’s body in abstract, cubist forms, we find her seeking to study Anatolian women, who shoulder all the burdens of life, but are also somehow helpless and hunched. The best examples include ‘Woman Has No Name’ (Kadının Adı Yok), ‘Being a Woman’ (Kadınlık), ‘Young Girl’ (Genç Kız), ‘Mother and Child’ (Ana Çocuk), and ‘Nude’ (Çıplak).

Recent works display a clearer shift towards the abstract. “Nowadays there is a return to conceptual art,” Çetintaş observes. “The abstract, in my view, is a form for presenting things which occur in nature and in ideas, and for interrogating the world of the artist’s experience, and for the sculptor to create objects of his or her own.”

At the time of her graduation, the sculptor experimented with the then newly-developed, “concrete plastering technique” for her 1.70 metre ‘Children Playing’. Six personal exhibitions and more than thirty competitive and joint exhibitions later, she is still experimenting – this time with the combined use of marble and bronze.

MFA Gallery: Chic links

By Sibel DORSAN

Artistic events have long helped to consolidate friendships between nations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Ankara has taken the idea a step further by opening an art gallery on its own premises. Originally conceived with the Ministry staff in mind, the gallery is also open to the public.

Ankara has innumerable art venues, but there is always room for one more – especially one located in the sharp, spacious surroundings of a truly modern building. Curiously, it all came about more by “accident” than “design”. This space was not built as a gallery, but as part of the new headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the up-and-coming Balgat district. To display art was the brainwave of Deputy Undersecretary Ambassador Ahmet Erozan.

Perhaps the plain white walls and wide illuminated corridors whispered something into the Ambassador’s ear. For barely weeks after the Ministry moved in, the spotlights had been adjusted and the picture hooks were in place. On May 2 this year, as part of the Ministry’s 86th birthday celebrations, a joint exhibition of works by 33 Ankara-based artists brought the impromptu gallery to life.

Bilateral cinema

“Initially, we aimed to create a warm atmosphere.” states Erozan, pointing to the many meeting halls which open onto the corridors. Exhibitions of art works would provide an ‘ambiance’ in which to forget the stress of an intensive working day. But already the gallery has been taking on other functions. Ministry officials and their colleagues in Ankara’s foreign missions are finding common ground as they tour the exhibitions. Turkish art and artists are being promoted to an international audience. And other countries are seeking a look-in.

A display of photographs of Romanian architecture is just one of the events scheduled for next year. This summer, the terrace was twice turned into an open-air cinema as Russian and Chinese films were screened with the support of the two countries’ embassies. Once the construction of a closed hall, with a capacity of 150 people is completed, it will be possible to hold movie nights and musical performances all year round.

Praise for Gürsöz

Nuri Abaç, Şeref Bigalı, Şefik Bursalı, Turan Erol, Yalçın Gökçebağ, Hayati Misman, Adnan Turani, Osman Zeki Oral… The programme for the first exhibition read like an A-Z of contemporary Turkish painting. Next to grace the walls were the photographs of Levent Bilman. The contrasting and highly original creations of Ercan Gülen and Sıtkı Olçar went on show in October.

If the idea came from Erozan, then most of the hard work has been shouldered by curator Hatice Gürsöz. “Without her, we would never have got this far,” he says. The MFA Gallery may not be the most accessible from city centre streets. But more and more art-lovers may soon be finding their way there. Watch www.mfa.gov.tr > Ministry > cultural events.

World view

Direct democracy: The Libyan experiment

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV

Libya is not only a republic. Officially, it does not call itself a ‘Jumhuriya’. Instead, it is described as a ‘Jamahiriya’, meaning a republic with a system of direct democracy. Not too many non-Libyans are aware that this North African country, conquered several times in the past – and which lost thousands of its citizens, including the legendary hero Omar Mukhtar, as martyrs, to colonialism – has been experimenting since the late 1970s with a governmental policy and practice that enables it to credit its own society as being ahead of a number of Western regimes that have habitually claimed to be the cradle of democracy.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, having escaped from wars, poverty and discrimination in the Old World, rebelled in the New World against the prerogatives of the British king and claimed to have created a system of separation of powers and checks and balances. The British realized the Magna Carta, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and everything else that followed them, including several Labour Party governments. The French and the Russians wrote the achievements of two great revolutions down in the annals of history. The Turks gave up much of the Ottoman past that was dead wood anyway. Former colonial societies like India have presented the world with some new ideas in governance. While Japan gave up its militaristic past, some African peoples found in their ancient past traces of ‘Ujamaa’, or socialisation, and South Africa abandoned the hated system of apartheid. The guiding spirits of Simon Bolivar, José Marti and Zapata may be seen in several corners of Latin America.

The question is: which ideas survived since the American Revolution? What is the character and scope of the consensus of the two leading political parties there? The House of Commons is supreme in Britain, but should the British model be imitated elsewhere? The Blacks of Africa finally placed the crown on their own heads, but where are the jewels of the crown? The Brezhnev Doctrine is dead; what about the Monroe Doctrine?

A different experiment

The Libyan experiment has been different. The First of September Revolution (1969) there triggered many changes. The General People’s Congress held its first meeting in 1976, and “People’s Authority” was declared to have been established in early 1977. Since then, the Libyans claim to have announced the dawn of the era of the masses, or popular direct authority, as the basis of their political system. The man on the street, as much as the elite, believes that that the people exercise their authority through the popular congresses, the people’s committees and other bodies, and ultimately through the General People’s Congress.

Libya conceptualizes sovereignty and democracy in a different way. It has created institutional arrangements to give practical effect to these concepts. These institutions function in their own prescribed way to implement the notions of sovereignty and democracy so conceived. Short answers to these questions should be as follows: The decisions taken and implemented should reflect the sovereign will of the whole people, and not that of any class, clan, fraction or individual; they should be implemented in a way which reflects the sovereign will of the whole, not any part of it. The people, locally and nationally, should participate directly in decision-making and in the implementation of decisions, and should use their right to control the results. Hence, direct rule, not representation.

Principles and practice

The basic principles as to how these objectives can be achieved may be found in M. Al-Qaddafi’s ‘The Green Book’. There are also research and publication centres in Tripoli, led by Dr. R. Budabbus, Dr. Abdullah Osman and Salem Hamza, that have printed various elaborations on the Libyan political system, often referred to as the Third Universal Theory. A number of foreign commentators have erroneously assumed that this theory prescribes state ownership and control. Some of them, like David Blundy and Andrew Lycett, fail to offer concrete and detailed discussion of what goes on at the people’s congresses. Another, Martin Sicker, is entirely one-sided.

I happen to have some first-hand knowledge about the working of those meetings, in which all citizens may participate. I also know that the Libyan leader is at times criticised there. Moreover, there are cases in which his suggestions are turned down by popular vote and the exact opposite is adopted and recommended for legislation. For instance, M. Al-Qaddafi repeatedly suggested the elimination of capital punishment but the people’s congresses decided to maintain it for some crimes, and the latter prevailed.

There exists a group of Libyan and African researchers like Abdul Salam Al-Tunji, M. L, Farhat, A. A. Awan and A. Yeboah, on the other hand, who give information based on the true nature of this unique development.. Some old publications, for instance those of H. Habib, are no longer of any use because they dwell on the period before the major changes that instituted the Jamahiriya. The new ones should help clear out several misconceptions, fed by the prejudices of unfriendly witnesses and by the lack of accounts on the processes that take place on the ground in Libya. There is room for critical interpretations, but facts should also be laid bare. While favourable bias should not blind one to shortcomings, prejudices should not emphasize defects that do not exist.

Authority and participation

The limited space available here does not permit a detailed treatment of the institutions and structure of ‘Sulta el-Shaab’ (People’s Authority) and its twin component ‘Shuraka la Ujara’ (Partners, Not Wage Earners). In the early 1970s, ‘Lijan Shaabiya’ (People’s Committees) emerged all over the country to serve as the means by which the people themselves could exercise direct control over the running of public affairs. This initial step brought a degree of decentralization in the political process, formally subordinated the administrative apparatus to popular wishes, and pointed at the direction of collective decision-making. The 1977 Declaration proclaimed the establishment of direct democracy. According to its wording, the citizens at large, through the General People’s Congress, replaced the Revolutionary Command Council as the highest political authority, and the General People’s Committee, appointed by the General People’s Congress, replaced the Council of Ministers as the highest executive body.

Central in current Libyan political thought is the notion of people’s sovereignty, which (as well expressed by Abdul Fatah Shahada in his book ‘Democracy’) is the “sum total of individual sovereignties.” The assumption is that the latter may be maintained only if the individual has the opportunity to contribute directly, and not through representatives, to the decision-making process. Hence, all Libyan citizens are expected to reflect their views directly – not in one parliament of a few hundred deputies, but in hundreds of congresses utilised by tens of thousands of ordinary citizens. Such a multitude will necessarily exhibit differences of opinion, which will clash and possibly harmonise, as much as possible, through open debate. Committees, elected by such congresses, are accountable only to the people and may be recalled or changed by them, but are expected to execute definite decisions. The Libyan system uses the word ‘elevation’ instead of ‘election’, and avoids the campaigning that characterizes classic political parties and rewards only the well-to-do.

Making policy

‘Al-Mu’tamar al-Shaabi al-Asasiya’, the Basic People’s Congress, is organised on a territorial basis and is the primary institutional vehicle through which the men and women in the street voice their opinions. These congresses have judicial power to issue legislation, draw up economic plans, ratify agreements, formulate public policies, and “elevate” as well as supervise committees. The “non-basic congresses”, on the other hand, integrate the resolutions of the basic ones. There are also vocational congresses, set up in corporations, production units and other institutions. Apart from the local ‘Al-Mu’tamar al-Baladiya’ or the Municipal People’s Congresses, there is the ‘Al-Mu’tamar al-Shaabi al-Amm’, which is the national coordinating organ of all the people’s congresses. All resolutions are thus eventually streamlined into binding public policies.

It would be possible to elaborate further on the structure and application of the system. Even from the above, however, one can deduce, that Libyan society is trying to avoid the subjugation of the majority, and argues that the system of governance in Western societies favours the interests of monopoly capital, whereas and in the former Stalinist models it favours the single-party apparatus. This unique system in Libya has, according to some commentators, some shortcomings, inter alia, in terms of attendance, initiative to speak up, and effective control. Nevertheless, the experiment should arouse interest especially among those studying democratic theory and practice. It merits serious – and not prejudiced – consideration.

Knidos: Where love came first

by İlknur Taş

photos/research: Recep Peker Tanıtkan

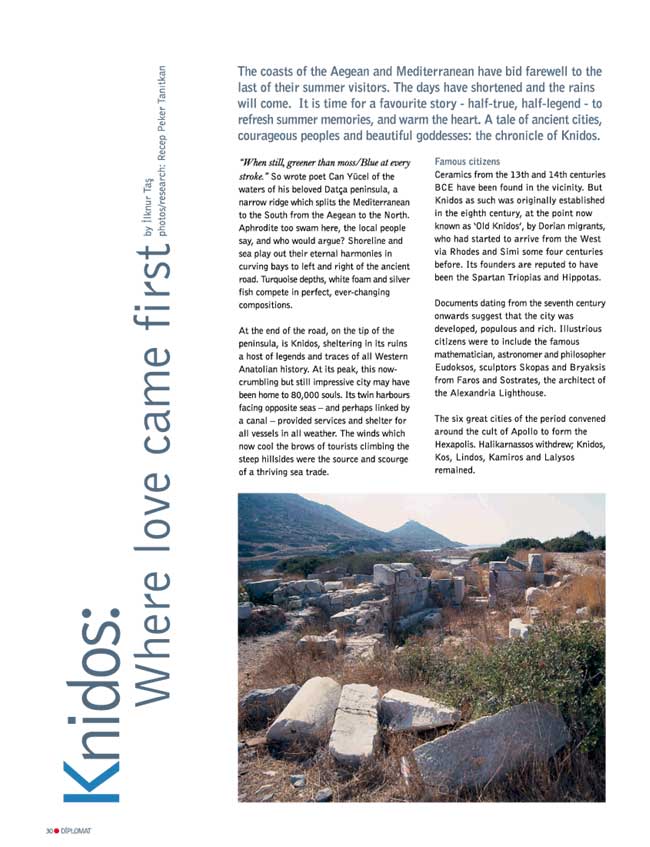

The coasts of the Aegean and Mediterranean have bid farewell to the last of their summer visitors. The days have shortened and the rains will come. It is time for a favourite story – half-true, half-legend – to refresh summer memories, and warm the heart. A tale of ancient cities, courageous peoples and beautiful goddesses: the chronicle of Knidos.

“When still, greener than moss/Blue at every stroke.” So wrote poet Can Yücel of the waters of his beloved Datça peninsula, a narrow ridge which splits the Mediterranean to the South from the Aegean to the North. Aphrodite too swam here, the local people say, and who would argue? Shoreline and sea play out their eternal harmonies in curving bays to left and right of the ancient road. Turquoise depths, white foam and silver fish compete in perfect, ever-changing compositions.

At the end of the road, on the tip of the peninsula, is Knidos, sheltering in its ruins a host of legends and traces of all Western Anatolian history. At its peak, this now-crumbling but still impressive city may have been home to 80,000 souls. Its twin harbours facing opposite seas – and perhaps linked by a canal – provided services and shelter for all vessels in all weather. The winds which now cool the brows of tourists climbing the steep hillsides were the source and scourge of a thriving sea trade.

Famous citizens

Ceramics from the 13th and 14th centuries BCE have been found in the vicinity. But Knidos as such was originally established in the eighth century, at the point now known as ‘Old Knidos’, by Dorian migrants, who had started to arrive from the West via Rhodes and Simi some four centuries before. Its founders are reputed to have been the Spartan Triopias and Hippotas.

Documents dating from the seventh century onwards suggest that the city was developed, populous and rich. Illustrious citizens were to include the famous mathematician, astronomer and philosopher Eudoksos, sculptors Skopas and Bryaksis from Faros and Sostrates, the architect of the Alexandria Lighthouse.

The six great cities of the period convened around the cult of Apollo to form the Hexapolis. Halikarnassos withdrew; Knidos, Kos, Lindos, Kamiros and Lalysos remained.

The lion and the goddess

The first systematic excavations began thanks to Sir Charles Newton, who was working in Bodrum on behalf of the British Museum. Ottoman disinterest enabled the Museum to acquire some of the early findings, including a three-metre sculpture of a lion, which once decorated a tomb. The statue and other Knidos artefacts continue to amaze visitors to London. But the statue of a goddess known as the “naked Aphrodite” and referred to by Roman author Plinius, has yet to be found. Only its copies are extant.

The legend begins in the 4th century BCE, when famous sculptor Praxiteles receives an order from Kos for a statue of the goddess. Praxiteles presents two marble sculptures, of which one shows Aphrodite completely naked. Until then, sculptures of gods had depicted them naked, but goddesses had always been represented with a part of their bodies draped in cloth. The naked Aphrodite merely has one hand over her crotch; the other hand holds a cloth, but she is holding it away from her body. Kos opts for the classic statue, and poorer Knidos offers to buy the naked one. The eye-catching image is placed in the temple, where it can be seen from all directions – even from the decks of ships approaching the harbour.

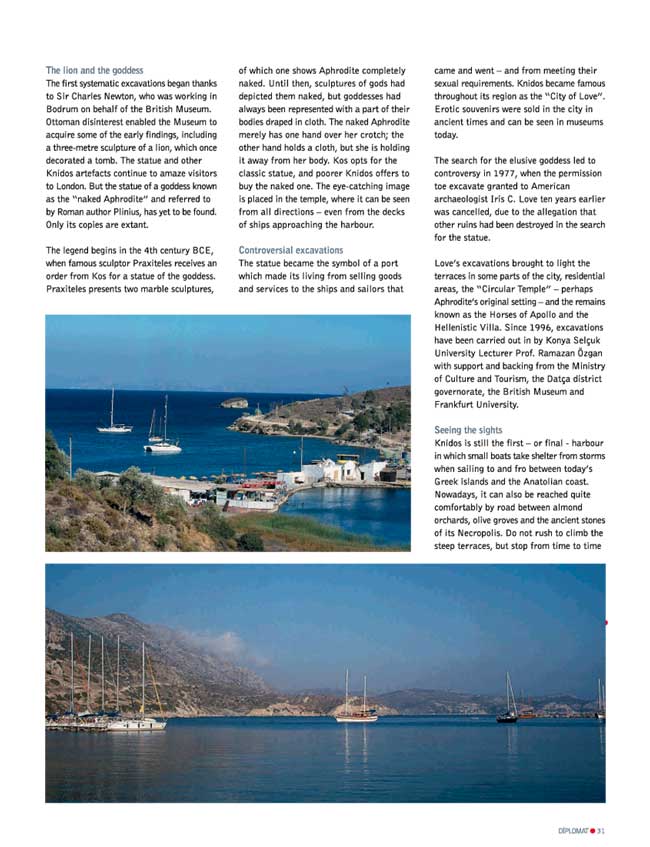

Controversial excavations

The statue became the symbol of a port which made its living from selling goods and services to the ships and sailors that came and went – and from meeting their sexual requirements. Knidos became famous throughout its region as the “City of Love”. Erotic souvenirs were sold in the city in ancient times and can be seen in museums today.

The search for the elusive goddess led to controversy in 1977, when the permission toe excavate granted to American archaeologist Iris C. Love ten years earlier was cancelled, due to the allegation that other ruins had been destroyed in the search for the statue.

Love’s excavations brought to light the terraces in some parts of the city, residential areas, the “Circular Temple” – perhaps Aphrodite’s original setting – and the remains known as the Horses of Apollo and the Hellenistic Villa. Since 1996, excavations have been carried out in by Konya Selçuk University Lecturer Prof. Ramazan Özgan with support and backing from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Datça district governorate, the British Museum and Frankfurt University.

Seeing the sights

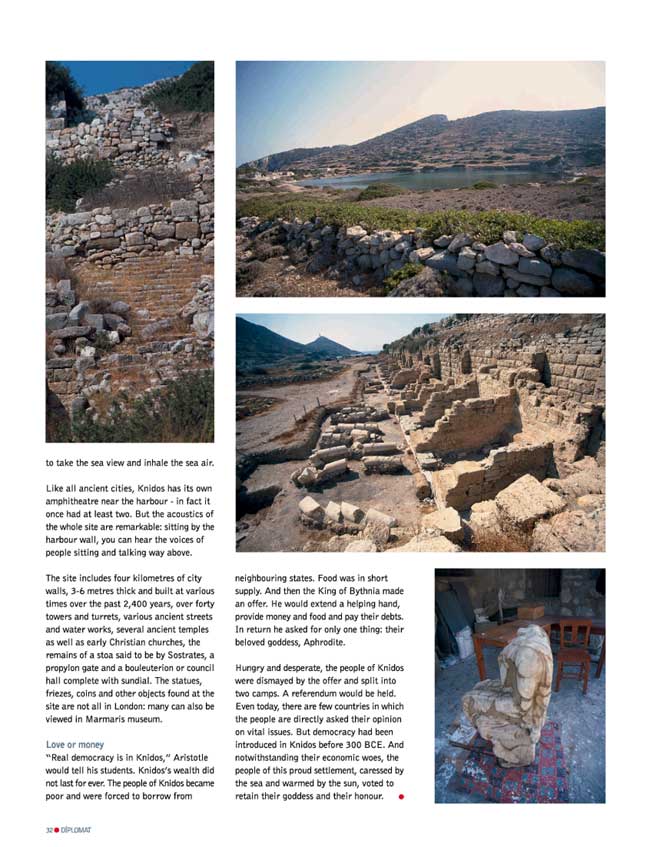

Knidos is still the first – or final – harbour in which small boats take shelter from storms when sailing to and fro between today’s Greek islands and the Anatolian coast. Nowadays, it can also be reached quite comfortably by road between almond orchards, olive groves and the ancient stones of its Necropolis. Do not rush to climb the steep terraces, but stop from time to time to take the sea view and inhale the sea air.

Like all ancient cities, Knidos has its own amphitheatre near the harbour – in fact it once had at least two. But the acoustics of the whole site are remarkable: sitting by the harbour wall, you can hear the voices of people sitting and talking way above.

The site includes four kilometres of city walls, 3-6 metres thick and built at various times over the past 2,400 years, over forty towers and turrets, various ancient streets and water works, several ancient temples as well as early Christian churches, the remains of a stoa said to be by Sostrates, a propylon gate and a bouleuterion or council hall complete with sundial. The statues, friezes, coins and other objects found at the site are not all in London: many can also be viewed in Marmaris museum.

Love or money

“Real democracy is in Knidos,” Aristotle would tell his students. Knidos’s wealth did not last for ever. The people of Knidos became poor and were forced to borrow from neighbouring states. Food was in short supply. And then the King of Bythnia made an offer. He would extend a helping hand, provide money and food and pay their debts. In return he asked for only one thing: their beloved goddess, Aphrodite.

Hungry and desperate, the people of Knidos were dismayed by the offer and split into two camps. A referendum would be held. Even today, there are few countries in which the people are directly asked their opinion on vital issues. But democracy had been introduced in Knidos before 300 BCE. And notwithstanding their economic woes, the people of this proud settlement, caressed by the sea and warmed by the sun, voted to retain their goddess and their honour.

Philately

Atatürk’s first anniversary

by Kaya DORSAN

Having celebrated the 82nd anniversary of its establishment on October 29, the Republic of Turkey commemorated its founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, on November 10, the 67th anniversary of his death.

The anniversary of Atatürk’s death has been marked by the issue of special stamps once every five years since 1953. But the first stamp series issued in memory of Atatürk was printed back in 1938, just after his death, as a mourning series. These stamps were produced by partially overprinting definitive stamps bearing Atatürk’s portrait which were in use in the postal service at the time.

The overprint, made in one day at a printing house in Ankara, carried the date November 21, 1938, written on a horizontal thick black line. This was the day when Atatürk’s body was brought from Istanbul to Ankara and interred at today’s Ethnography Museum.

First miniature sheet

A splendid commemorative series was planned for Atatürk in 1939. The Courvoisier Printing House in Switzerland was commissioned to print a series consisting of a commemorative miniature sheet and eight stamps. However the printing house was only able to deliver the 2 ½, 6 and 12 ½ kuruş stamps in time for November 10. Accordingly, only these three stamps could be issued on the actual anniversary of Atatürk’s death. The other denominations and the miniature sheet were put on sale on January 3, 1940.

The miniature sheet of 100 kuruş was a first in Turkey. Since then, more than 60 miniature sheets have been printed on various themes.

Birth date riddle

The year when Atatürk was born is known as 1881. However, the stamps printed on the first anniversary of his death give his date of birth as 1880. Is this an error? Or is it a calculation mistake made when the Arabic calendar was replaced by the universal calendar?

There are many philatelists in Turkey who collect only the stamps of Atatürk. One of them may have solved this riddle by now.

Speaking Out

David Winter: Engineering for people

As you read this, crude oil from the Caspian Sea basin is making its way across Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey through the newly-built 1,768km Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline. Within a matter of weeks – and less than three-and-a-half years since the partner group sanctioned the construction phase of the project – the oil will arrive at the Ceyhan terminal on the Turkish Mediterranean coast, ready for transportation to world markets. David Winter has been involved with the project since the planning stage, as Technical Compliance and Health & Safety Manager and a member of the Core Management Team. In July of this year he moved from Baku to Ankara to assist with the final completion phase of the project in the capacity of BTC Project Manager Turkey. We asked him to comment on the achievements of the project and their significance for us all.

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline is the first major energy project of the twenty-first century. Initially, it aims to meet just a small fraction of the demand for oil in world markets – albeit enough to justify the technical feasibility. For the countries concerned, the results are very meaningful:

– The association of the three neighbouring countries creates an environment of cooperation and solidarity in every area.

– The project makes a direct contribution to the economies of these countries in the form of transport and operation fees.

– The project also boosts the welfare of local people through the investments made, the use of local firms, the employment of local workers and the local purchase of goods and services.

– The social, environmental, health and safety investments will provide additional benefits to the region. The most important characteristic of these projects is that they have long-term sustainability. Let us not forget that we plan and desire to be neighbours with the local people from any years to come as a result of this BTC project.

Of course, I cannot fail to underline the strategic importance of the project for Turkey in particular. Istanbul is one of the most beautiful cities in the world and currently struggles with a heavy traffic of tankers. As a continuous and reliable transport alternative with a capacity of 50m tons/year, the BTC Project will keep about 360 tankers a year away from the Straits traffic.

The size of the challenge

Negotiating host and intergovernmental agreements and putting in place the financial agreements and negotiating contracts was not easy. However, the implementation of the engineering and construction works was perhaps even more challenging.

Onshore pipelining is recognised as one of the most hazardous of all construction activities. During the construction of BTC, we have had to face up to, manage and mitigate issues relating to health and safety, to communicate with a workforce involving 30 different nationalities, to overcome infrastructure difficulties, to work and install pipe at heights in excess of 2,300 metres and in extremes of temperatures ranging from -40˚C to +40˚C, to install the pipeline under major rivers, and to deal with seismic engineering and construction issues. The project crosses 1,500 watercourses, and 3,000 roads, railways and utility lines. It has driven over 200m km moving pipe, materials, equipment and people.

Man-hours worked are expected to reach 110m at project completion. Turkey accounts for 52m of the total number of man-hours worked to date. In the most active period of the work, the number of personnel employed in the Turkish section of the project reached 12,000. Across the three countries which the pipeline traverses – Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey – we had 21,000 people working at the peak of construction.

We have maximised the number of unskilled or semi-skilled workers from the local people. Today, we can proudly say that all these personnel have been given all kinds of training in their areas of work and many of them have learned a trade.

Health and safety

The BTC project aimed to make a step change in the areas of health, safety and protection of the environment. The goal, simply stated, was “No accidents, no harm to people and no damage to environment”. Participants were trained long before site work commenced. We provided 868,097 hours of health and safety training and assessed operators and drivers before they drove vehicles or operated machinery. We adopted the highest standards for equipment, plant and vehicles, employed risk-reducing technologies such as vacuum lifting, and transported pipes by rail instead of road. In the BTC Turkey project, the frequency of days away from work was four times better than the rate achieved by the International Pipeline and Offshore Contractors Association.

Driving safety training was given to more then 5,000 drivers. Night driving was ruled out, speed limits were reduced, seat-belt use was enforced and a zero tolerance policy was implemented for alcohol and drugs. In 130m km of driving in BTC Turkey, there were 182 road traffic accidents.

Our health and safety know-how has been shared and will continue to be shared with public bodies, communities along the pipeline route and the general public. For example, an interactive video-based community safety awareness programme is about to be launched in Turkish primary schools, and the project’s STD/HIV awareness programme is being disseminated widely. The health and safety programme will continue throughout the operation of the Pipeline.

Security and human rights

Security is primarily the responsibility of host governments. At the same time, the route was directed as far away as possible from areas with known security concerns. The pipeline and related facilities were designed to facilitate protection and surveillance. Risk assessments have been carried out routinely. All people associated with the project have been briefed on security, and on the local culture and traditions. Unarmed guards from local communities protect manned facilities. Security performance is periodically audited by external assessors.

Simultaneously, efforts have been made to ensure respect for human rights and ethical police and military behaviour. The Joint Statement signed by BTC Co and the three host governments in May 2003, emphasising their determination to make the BTC project a model in all respects, made the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights part of the law governing the BTC project. To our knowledge, this is a first. The principles – which were launched by the UK and US governments, NGOs and major extractive industry companies in December 2000 – envisage risk assessments, the reporting of allegations, and human rights training and education. Support has been given to a human rights based theoretical and practical training programme led by Geneva-based Equity International.

Protecting the environment

The pipeline will be safe, silent and unseen. Before any construction work began, an Environmental Impact Assessment was carried out which gathered more than 11,000 pages of information on geological, biological, cultural and social factors over a 500 metre-wide corridor following the whole of the proposed pipeline route. The findings of this study led to refinement of the route and fed into measures to mitigate environmental and social impacts.

The route passes through about 500 settlements, some in economically disadvantaged regions, and areas of great biological importance. For example, 44 of Turkey’s 158 globally threatened plant species occur within the corridor. Besides construction-related mitigation measures, BTC Co formed working partnerships with NGOs, universities, consultancies and local communities to implement a series of Community and Environmental Investment Programmes, with their own staff and budgets (a total of US$12.3m for Turkey). Community investment projects include school and well repairs, waste management and recycling projects, educational activities and longer-term sustainable rural development projects. Environmental projects are studying ecosystems and endangered species and making plans for their conservation and management.

A joint effort

Schedule and cost over-runs are always a possibility with mega projects such as BTC. Many factors come into play from changes in governments to unexpected construction delays due to unforeseen extremes of weather. BTC has experienced these and a number of other unforeseen problems. However, the consequent slippage to schedule completion and resultant cost increase is comparable with industry benchmarked norms for such overruns. The project is deemed to be a success.

This project is above all the product of a joint effort and commitment. Credit goes to all the parties who conceived the BTC project as an idea, who studied its feasibility and believed in it, supported the project and committed themselves to it. Special mention must be made of:

– the countries in which the pipeline route is located, namely Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey;

– the Main Export Pipeline Participants, who made an early commitment to participate in the project, supported it, played an important role in the making of the agreements, and signed them;

– the partners in the BTC Company, consisting of the eleven companies that committed the investment (BP, SOCAR, Unocal, Statoil, TPAO, Eni, Total, Itochu, Inpex, ConocoPhillips and Amerada Hess), and the operating partner BP, which has shown patience and skill, faithfully implementing its golden principles and its concept of health, safety and security, with all the importance it attaches to these issues;

– the lenders, the international finance institutions including organisations such as the EBRD and the IFC. Here, we are talking about some 208 documents and 17,000 signatures, and

– the non-governmental organizations, which have been of great help with their guiding wishes and criticisms in the prevention and/or minimisation of damage to the environment, people and property during the execution of the project and in the implementation of international projects.

Lessons for the future

An important feature of this project is the association of the government and the private sector, and the different dimension this gives to relations. We have conducted this work hand in hand with the authorised units and officials of the State at every level and with the local people in more than 300 settlements in the ten provinces through which the pipeline passes. The State institutions have given us full support. We have learned much from them. The project has taught us that one can achieve everything if one wants it and commits oneself.

We have learned not to make mistakes in regional development, to pay attention to the values of the community, and the responsibilities of living close with the local people. We have seen that one must believe in people and that a correct investment to be made for them does not go unreturned. In addition, this project has awakened in us the excitement for watching developments and generating and implementing projects where needed by acting wisely and with concern.

For me personally, there have been many memorable moments. Just being part of such a great project is in its self memorable. I have seen achievements beyond my wildest dreams in the areas of health and safety, environmental compliance, the delivery of outstanding social commitments – and, above all, the sheer dedication of all those who have played a part in delivering this monumental project.

Course of history

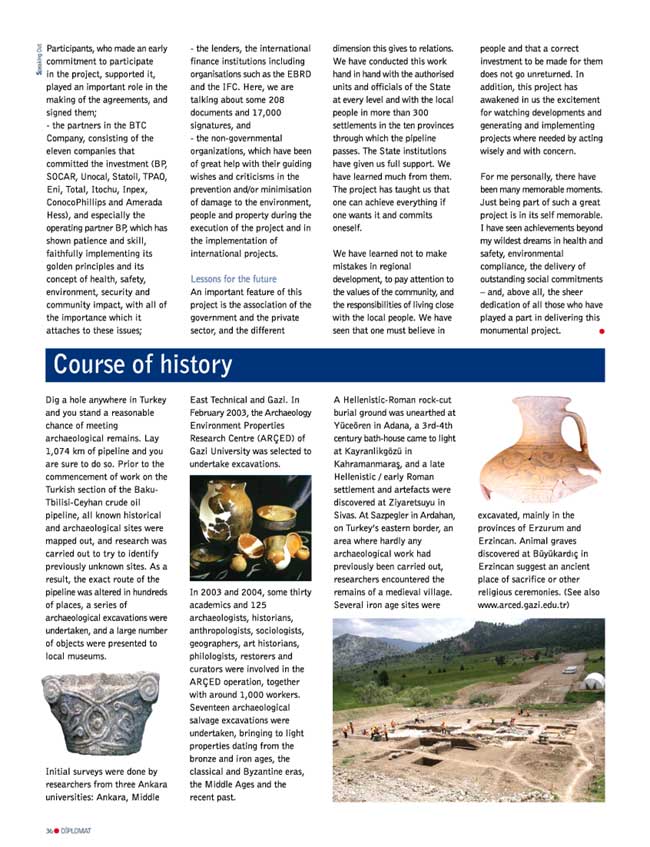

Dig a hole anywhere in Turkey and you stand a reasonable chance of meeting archaeological remains. Lay 1,074 km of pipeline and you are sure to do so. Prior to the commencement of work on the Turkish section of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline, all known historical and archaeological sites were mapped out, and research was carried out to try to identify previously unknown sites. As a result, the exact route of the pipeline was altered in hundreds of places, a series of archaeological excavations were undertaken, and a large number of objects were presented to local museums.

Initial surveys were done by researchers from three Ankara universities: Ankara, Middle East Technical and Gazi. In February 2003, the Archaeology Environment Properties Research Centre (ARÇED) of Gazi University was selected to undertake excavations.

All the work was done in accordance with agreements between the Turkish state pipeline company BOTAŞ (the chief contractor for the Turkish section of the line), the Ministry of Culture and the Centre. It was governed by all relevant international standards and conventions and guided by the Cultural Heritage Management Plan which formed part of the Environmental Impact Assessment for the BTC project.

Rock-graves and cults

In 2003 and 2004, some thirty academics and 125 archaeologists, historians, anthropologists, sociologists, geographers, art historians, philologists, restorers and curators were involved in the ARÇED operation, together with around 1,000 workers. Seventeen archaeological salvage excavations were undertaken in Ardahan, Kars, Erzurum, Erzincan, Sivas, Kahramanmaraş and Adana provinces, bringing to light archaeological and cultural properties dating from the bronze and iron ages, the classical and Byzantine eras, the Mıddle Ages and the recent past.

Most of the sites excavated within the scope of BTC Project yielded archaeologically significant results. A Hellenistic-Roman rock-cut burial ground was unearthed at Yüceören in Adana, a 3rd-4th century bath-house came to light at Kayranlikgözü in Kahramanmaraş, and a late Hellenistic/early Roman settlement and artefacts were discovered at Ziyaretsuyu in Sivas. At Sazpegler in Ardahan, on Turkey’s eastern border, an area where hardly any archaeological work had previously been carried out, researchers encountered the remains of a medieval village. Several iron age sites were excavated, mainly in the provinces of Erzurum and Erzincan. Animal graves discovered at Büyükardıç in Erzincan suggest an ancient place of sacrifice or other religious ceremonies. (See also www.arced.gazi.edu.tr)

Rule of Law

Extradition of offenders

by Murat Demir & İbrahim Yüce

The extradition of suspects or offenders refers to the hand-over of a person, in connection with an offence committed in another country, by a state which is not authorized to try the person to a state which is authorized to do so, so that the offence can be prosecuted or the penalty imposed can be enforced.

The “right of refuge” and the “sovereign rights of states” used to be invoked frequently as grounds for refusing requests for extradition. This approach has now been abandoned and the need for extradition has generally been recognised on a basis of sound legal principles. The legal principles on which the need for extradition is based can be summed up as: “justice” and the “protection of mutual interests”. Extradition makes it possible for a suspect to be tried by his or her natural judge, so that wherever a crime is committed, its perpetrator does not go unpunished. In this way, it acts as a vehicle for making sure that justice is done. In addition, extradition allows states to join forces to prosecute offenders and investigate and prevent crimes. The state which is requested to make the extradition order is able to rid itself of a foreign suspect or offender, and gains a way of providing and protecting order and justice on its own territory.

A little history

Until the 19th century, extradition was an act of government which depended on the condition of reciprocality. In 1833, a law on the extradition of offenders was adopted in Belgium. This law constituted a model for the laws that were subsequently to be adopted by other countries concerning the same issue. Turkey did not adopt specific laws for extradition, but was content to include certain principles in its Penal Code. At the same time, it reached bilateral agreements concerning extradition with a large number of states. Finally, under Law No. 7376 of November 18, 1959, Turkey approved the European Convention on Extradition, which had been adopted by the Council of Europe in 1957, and Turkey became a party to the Convention.

Constitutional prohibition

Currently, the sources of domestic legislation relevant to the extradition of offenders are the final clause of Article 38 of the 1982 Constitution, Article 18 of the Turkish Penal Code, the bilateral agreements on the extradition of offenders reached with various states at various times and the European Convention on Extradition.

Article 38 of the Constitution ends by stating that, “A citizen cannot be returned to a foreign country on account of a crime.” The rule that citizens should not be extradited is an established principle in extradition law. Article 6 (a) of the European Convention also stipulates that parties to the convention shall have the right not to extradite their own citizens.

Exceptional cases

Article 18 of the Penal Code (Law No. 5237) which took effect on June 1, 2005 makes more detailed arrangements for extradition than the relevant article (Article 9) of its predecessor (Law No. 765). The effect has been to ensure parallelism between the Code and the European Convention.

Article 18 sets out a series of exceptions and procedures for the extradition of offenders. The exceptions, in which circumstances the request for extradition cannot be accepted, cover the following cases:

-where the offence on which the request for extradition is based is not an offence under the laws of Turkey;

-where the offence in question is a crime of thought or a political or military crime;

-where the offence has been committed against the security of the Turkish state or to the detriment of the Turkish state, a Turkish citizen or a legal person established in accordance with Turkish law;

-where Turkey has authority to try the offence;

-where the case has been subject to an amnesty or has lapsed due to passage of time;

-where the offender is a Turkish citizen;

-where there are strong grounds for suspicion that the person, if extradited to the state making the request, will be persecuted or punished on account of his or her race, religion, citizenship, appurtenance to a certain social group or political views, or will be subject to torture or mistreatment.

How it works

If a request for extradition is correctly made to Turkey, then the response is given according to the procedures set out in paragraphs 4-8 of Article 18. Upon the receipt by the Turkish authorities of a request for extradition, the criminal (‘ağır ceza’) court in the place in which the person is to be found may decide whether or not the extradition request is acceptable under the terms of Article 18 of the Penal Code and of the international agreements to which Turkey is a party. The same court may also decide to take precautions concerning the person in question or to arrest him or her. The decisions of the court are subject to appeal. If the court decides in favour of extradition, then the Council of Ministers has the discretion to decide whether or not to carry out the order. In the event of extradition, the person may only be tried for the offences on the basis of which the extradition order was given or made to serve the penalty for which he or she has been sentenced.

Bilateral and multilateral accords

The bilateral agreements to which Turkey is a party provide for extradition on a basis of reciprocality by diplomatic means. Generally speaking, the grounds cited in the European Convention on Extradition as justifying the refusal of a request for extradition are also included among the grounds for refusal named in the bilateral accords.

As already noted, Turkey became a party to the Convention in 1959. Article 28 of the Convention states that it takes the place of bilateral accords. If the offence has been committed in the state to which the request for extradition is made, then this state will turn down the request on the basis of Article 7 of the European Convention. In addition, the state receiving the extradition request may refrain from extraditing a person where the offence has been committed in a place which under its own legislation is partially or wholly within its territory or considered a part of it. If the offence has been committed outside the territory both of the state requesting the extradition and of the state from which the extradition is requested, then in principle the request ought to be approved. In such circumstances, however, a request for extradition may be refused if the law of the state receiving the request is conducive to the prosecution of the offence in-country.

Minimum penalty?

Insisting that the offence on the basis of which extradition is requested must be considered an offence in both of the countries concerned, the European Convention differs from the Turkish legislation in specifying, further, that the offence in question must be punishable under the laws of both parties by deprivation of liberty. Where a conviction has occurred or a detention order has been made, the period of punishment must be at least four months. The Convention makes clear that it is up to the authorities in the state receiving the extradition request to determine whether they consider an offence to be political or politically related. Even in the case of ordinary offences – let alone crimes of thought or political or military offences – both the Turkish legislation and the Convention provide for the non-extradition of the suspect where the state receiving the extradition request has substantial grounds to believe that the purpose of the request is to prosecute or punish a person on account of his race, religion, nationality or political opinion.

Making a request

In cases where Turkey requests an extradition, the Prosecutor of the Republic sends to the Ministry of Justice the original or approved copies of the conviction or detention order, accompanied by a report which specifies the date and place of the act which the extradition request relates to and provides information concerning the identity and distinguishing features of the person whose extradition is being requested. These documents are examined by the Ministry’s General Directorate of Penal Affairs. Where deemed appropriate, they are then sent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which carries out its own examination from the point of view of conventions and diplomacy. If the Ministry sees fit, the necessary documents and orders are sent out to the Turkish representative in the country where the person to be extradited is located so that the extradition request can be made.

Urfa Bazaar: Sparkling in the shade

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

Şanlıurfa is a city of mosques and prophets of all religions, of miracles and myths, ‘medrese’ and monasteries, tombs, museums and inns. Its ancient walls forever crumble but are never destroyed; its fish survive the centuries in their breathless medieval pools. Under the gaze of its citadel, prehistoric settlements and traditional dwellings bake in the sun. But today as in the past, the heart of the city throbs in the shade, where a thousand artefacts gleam, within the doorways of its dream bazaar.

If the southeastern city of Şanlıurfa, is an open-air museum, its çarşı or bazaar is its living, working centrepiece. While Urfa’s religious and secular monuments stand ready to be admired, the çarşı is its hands-on exhibition. The walls may be dated to at most a few hundred years, but the exchange of goods and words and symbols which goes on within them is both timeless and new: the product of time and culture, the present fleeting form of the unbroken reproduction of millennia. Colourful carpets and rugs are displayed without discord alongside the most developed electronic apparatus, copper boilers, Adıyaman tobacco and smuggled tea. Western fabrications and Far Eastern fabrics are bought and sold simultaneously.

First-time visitors find themselves in a labyrinth with many doors but no way out – or a film set with entrances and exits on all sides. The market zone is not to be explored easily or in haste; instead, you must wander lost from hall to hall and arch to arch, to become familiar with the many routes – the many ways to earn a living.

Moments in history