Project Description

3. Sayı

Stars

DİPLOMAT – OCAK 2005

3. Sayı

Diplomat

Ocak 2005

For everybody, a new year brings with it fresh hopes.

For the people of Turkey, 2005 also means a new place in Europe and a new Turkish lira.

For the DİPLOMAT team, the turn of the year brings with it many hopes. VVe hope that the diplomatic and foreign community will continue to read our magazine with interest. We hope to go on irnproving and broadening its content And naturally we hope that the number of new subscribers will go on mounting.

Many readers have received the first three issues of DİPLOMAT free of charge. From now on we are obliged to begin reducing the nurnber of free copies. A subscription will ensure that you receive your copy in the months to come.

This month we caught up vvith the Ambassador of India, H. E. M r Aloke Sen, on the eve of his departure for a new ambassadorial posting in Phnom-Penh. We aiso opened our pages to H.E. Dr Tamer Gazioğlu, ambassador of the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus. Ambassador Gazioğlu contributes an İnteresting commentary on recent developments surrounding the isiand.

Our travel pages feature an eye-opening toıır of distant Ecuador and, closer to home, a gazetteer of the rich archaeological sites of the Aegean province of Aydın. From the world of art, DİPLOMAT presents Nazan Günay, a young woman juggling with coiour in her striking abstract paintings.

News and pictures of Internationa! activity and diplomatic life are a regular feature of the magazine, în this context I would like to thank ali those embassies which have sent us Information about their activities. Ali contributions and suggestions from the embassies will be as welcome in 2005 as they were in 2004.

Happy New Year!

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current opinion

Dating games

by Bernard KENNEDY

The procession of key dates which epitomises Turkey-EU relations is to continue in 2005. Leaders of Turkish public opinion enthused about the EU Council’s conclusions in December although (or because) there was little to enthuse about. The commitment of public opinion to an open-ended accession process has persisted. Fresh traumas can be expected to put this commitment to the test in the years to come. But at the same time December 17 has made the process part of the furniture: the ball will keep rolling unless somebody stops it.

Turkey-EU ties were characterised in 2004 by a succession of climactic appointments with time. The most memorable are the Cypriot referenda of April 23, the ‘Progress Report’ of October 6 and finally the December 17 summit of EU heads of states and government. Previous years have followed a similar pattern, perhaps helping to explain the popularity of chronologies in press coverage of the 45 year-old relationship. For 2005, October 3 has been set as the nominal date for the start of accession talks – and the de facto deadline for Ankara to accept the Greek Cypriot administration as a customs union partner. News agencies are already filling out the calendar with the dates of other important meetings, the release schedules for the next reports and programmes, the countdowns to the Cypriot presidential elections and the steps to be taken by Turkish political, trade and judicial authorities.

Damaging debate

The December 17 celebrations were a little artificial – not so much a spontaneous outburst of joy as a deliberate morale-booster for a prime minister liable to meet with some cynicism on his return home from Brussels. This was only to be expected. The debates sweeping the core EU countries over the past 2-3 months have done little to alter Turkish perceptions of the EU as an exclusive club which seeks to keep Ankara at arm’s length, exerting control and tapping into strategic assets without making economic commitments or cultural concessions.

The human rights smoke-screen rose (perhaps temporarily), and the debate within the EU was played out on a more convincing level of cultural fears, concerns for jobs and potential financial burdens. Turkey’s uncertain public image in the north and west of the continent was verified repeatedly, and some significant politicians clearly signalled their determination to go on pouring fuel on sensitive issues and to ensure that Turkish membership remains an open question.

Stringent conditions

The conclusions of the EU Council were little more encouraging. After a polite grandmaster-level game of diplomatic chess among the EU capitals – marred only by some shouting on the part of the Turks and Greek Cypriots – the Council delayed the start of negotiations until the final quarter of 2005 (at the earliest). In line with the EU Commission’s October recommendation, democracy will continue to be monitored closely, and talks may be suspended. Benchmarks to be set for the commencement of talks in each individual area may include track records of implementation and pave the way for a painful long drawn-out process with individual governments wielding effective veto rights.

In addition, the leaders (or at least some of them) felt the need not only to emphasise that the talks will be “open-ended” but also to refer to a goal of keeping Turkey “anchored” to the EU if they fail. Presumably this is also intended to apply if any EU country rejects their outcome in a referendum.

“Specific arrangements”

If Turkey is to become a member, it will not be before 2014, and may be put back further depending on the EU’s absorption capacity. Going well beyond the Commission’s caveats, the Council also made clear that upon membership Turkey could anticipate “long transition periods, derogations, specific arrangements or permanent safeguard clauses” in areas such as freedom of movement of persons, structural policies or agriculture – that is, areas where Turkish citizens might once have hoped to derive some advantage from membership. Individual states are to play a maximum role when it comes to freedom of movement of persons. Against this, Ankara scored a diplomatic success (!) by having “permanent safeguard clauses” more carefully defined – it is the clauses, not the safeguards, which are to be permanent.

Arguably the basic conditions for membership remain the same as those which apply and have applied to other candidate countries. But in this case the EU Council has chosen to make all its caveats explicit. The procedures to be followed, although presented as guidelines for all ongoing and future accession processes, are unquestionably Turkey-specific

Meanwhile, the inevitable Cyprus condition only confirms the common Turkish observation (not policy) that admitting Greek Cyprus into the EU has prevented a settlement on the island. Surprisingly, Erdogan and the Foreign Ministry still appear to harbour hopes that the great powers will threaten the Greek Cypriots with an independent Turkish Cypriot state and so oblige them to accept something less than administration of the whole island by the Republic of Cyprus, recognised by Turkey. Such hopes are unlikely to be shared by the general public.

Better than nothing

None of this, however, means that Turkish opinion is quietly hardening either against the government or against the EU. Since December 17, the opposition has garnered little political capital – even where its various voices have been heard – by denouncing the government’s capitulations. As previously argued on these pages, influential and large parts of society believe their interests will be best served if Turkey treads the EU path, regardless of whether it leads to its logical conclusion.

The EU of Chirac, Schroeder and Schlussel – or of Berlusconi, Blair, Barnier and Balkanende – is a poor substitute for the idealised civilisation of which Turkey sees itself as a rightful member. But it is the only show in town, and for the time being it seems better than nothing. To believe so is not to trust in the outcome. Even though Turkey now has a date, it will come as no surprise if the next batch of opinion polls shows that the average Turkish citizen wants to join the EU as much as ever before, but still never expects it to happen.

Reality check?

Will this faithless support of the Turkish public persist indefinitely? Certainly it will face stricter tests. Turks have to confront painful revisions of their cherished positions not only on Cyprus – where the revisionism is already well under way – but on minority rights, the Aegean, trade with Armenia and other issues. The EU’s selective approach to democracy, with its emphasis on ethnicity rather than equality, will continue to provoke antipathy. The education system may need to be overhauled, with implications both for vested interests and for national ideology.

Meanwhile, meat and used car imports, the liberalisation of services and the adoption of EU models for public tenders, incentive policies, the environment, health standards, packaging and much else besides will raise costs and increase competition for medium and small-scale businesses and the self-employed. The more Brussels is involved in Turkey’s governance in these ways, the greater the risk that it will come to be seen (as in many member states from time to time) as a cause of the country’s problems instead of a solution. Any downturn in the economy could also mark a downturn for perceptions of the EU.

The normalcy factor

Against these risks, the forces in favour of the process now wield the weapon of normalcy. The conclusions of December 17 have made membership talks between the EU and Turkey sound matter-of-fact. The inhabitants of western Europe can be expected to adjust their own inner normalities to reflect this new phenomenon, in the same way as they have accommodated kebab shops, mobile telephones, the euro or the homeless on their streets. In Turkey, likewise, the EU has arguably become an “ongoing situation” no longer worthy of general interest or debate. Only 30% of TV viewers reportedly watched Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan’s triumphant return from Brussels on December 18. The remainder were absorbed in the finale of the reality show “Can I Call You Mother?” – incidentally another dating game in which would-be brides, having crossed the boyfriend hurdle, struggle for the approval of their putative mothers-in-law.

Interview

Ambassador Sen: New-found Confidence

Ambassador Aloke Sen of India has been one of Ankara’s best-liked ambassadors over the past three years, well known for his professionalism, modesty, thorough knowledge of the country and command of the Turkish language. It was in Ankara that Ambassador Sen began his diplomatic career back in 1978-1981. Having served in Bangladesh, Canada, Algeria and Uzbekistan as well as Delhi, he returned as ambassador twenty years later, in 2001. “I remembered much more Turkish than I expected,” he recalls, “It came back pretty quickly.” On the eve of his departure for a further ambassadorial position in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh, Diplomat spoke to Ambassador Sen about his experiences in Turkey, the development of Turkey-Indian relations, India’s growing economy and its role in world affairs. The interview was conducted by Bernard Kennedy.

Q How does the diplomatic community in Ankara compare to other capitals where you have served?

A Ankara is an attractive capital on two planes. First, it has an extremely active diplomatic community. Secondly, interactions with the local people are very exciting, because they are so open-minded and so interested in people from other countries.

Q Which country has changed more over the past 25 years or so – India or Turkey?

A In Turkey there have been tremendous changes in the way the cities look, the growth of the population, the standard of living… But the friendliness and hospitality of the people has not changed at all and that is a good thing because these heart-warming traits are tremendous assets of the country. Of course, both India and Turkey have changed a lot in terms of the economy – one extremely relevant front where countries can and should change. I think Turkey had a head start on India. The reform process started here in about 1981 whereas in India we started ten years after that in 1991.

Q How have ties between the two countries developed in your time as ambassador?

A Relations are strong and intensifying. It would be quite meaningless today to speak of a political and cultural relationship without an economic relationship. I derive some satisfaction from the way the economic relationship is changing. This is not a flash-in-the-pan phenomenon and I think it will continue. When I was appointed the two-way trade volume was $427 million. This year we are posting $1 billion. We are entering the projects sector, mainly infrastructure, in each other’s country. There are institutional arrangements in place. There is an economic commission and a business council. Direct flights between Turkey and India have resumed after a long interval. It’s only a six-hour flight but in the past the journey could take up to a day. One result of this is that a lot of business people have started visiting and discovering each other. They are starting to set up offices and find agents and representatives. There is mutual participation in trade fairs. A second consequence is the growth of tourism. Many Indians go abroad on holiday, and Turkey is a tourist’s paradise. But until recently very few Indians came here on holiday. Now I am sometimes pleasantly surprised to meet groups of Indians going around places where I would not have expected to see them.

Q What about political and cultural relations?

A During my watch, the prime minister of India came here after a gap of 15 years, and the Indian foreign minister visited for the first time in 27 years. We expect these visits to be reciprocated in the near future. Among other high-level visits, India was the first foreign destination for the speaker of the Turkish parliament. Following the prime minister’s visit in September 2003, we set up a joint working group to combat terrorism. This is a mechanism which India has with select countries. It is an important political initiative. In terms of our understanding of important regional and international issues there is a lot of convergence. There is no irritant in our bilateral relationship. Cultural relations are the bedrock of India-Turkey relations. There are so many commonalities. There are about 6,000 words which are common to Turkish and Indian languages. The people of India supported morally and materially Kemal Atatürk’s initiatives to set up a Republic and bring in deep reforms. They collected money and jewellery for Turkey. I keep hearing very kind references to this from people here. Atatürk was in turn an inspiring figure for the leaders of India’s own freedom struggle including our first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Q India’s economic performance has been attracting much attention of late…

A We commenced our liberalisation process rather late in the day but since then everybody has shown the necessary will to keep it on the rails. Considering that there has been so much instability in so many key economies in our region, it is pleasing to note that India has stayed out of harm’s way and posted growth of around 6% year after year. I think this reflects an innate strength of the economy. It’s a large economy and meets its own requirements to a large extent in industry, science and technology. There is a new-found confidence. We can be proud of our performance in areas like information technology, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology – areas which require research and development support. India is traditionally an agrarian country, but 50% of our GDP is now coming from services. So while some of our neighbours are achieving prosperity as a result of their excellence in manufacturing, India seems to be undertaking its own experiment in prosperity principally through the services route.

Q How does this affect your relations with other Asian countries including China?

A We are trying to contribute to the economic groupings in our region, SAARC and ASEAN, in order to create synergy and develop and grow together. China’s success is an opportunity for India. China is an important partner for ASEAN and they are talking about a free trade agreement to come into effect by 2010. India is also seeking to strengthen its institutional cooperation with ASEAN. So both bilaterally and regionally I think there is room for us to work together and grow together.

Q Is India’s economic growth adding to its international responsibilities? How do you see India’s role in the world system?

A India has played a tremendous role over the years as a responsible member of the international community in support of peace-keeping operations, humanitarian efforts and the like. At the WTO we have taken a leading role, trying to ensure that changes are not one-sided but reflect the needs of all concerned. We are a large country with a strong economy. For all these reasons, we think the voice of India should be heard more seriously in international forums. We are a candidate for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Judging by objective criteria – such as population, size, economic potential, civilizational legacy, adherence to important values like secularism and democracy and contributions to the activities of the UN – India eminently qualifies for the job. We think our presence in the Security Council would make the international architecture more representative.

Q How do you regard the phenomenon of fundamentalism, which seems to occur to some extent in all major religions? What causes it and if it is a problem, what is the remedy?

A Fundamentalism is an issue that is alarming everybody. Why and how it happens are complex questions. It may be caused by social alienation, economic deprivation or similar factors. But what I am sure about is that none of this can justify terrorism. Fundamentalism is bad because it goes hand in hand with terrorism. I think democracy gives us the wherewithal to handle problems in a mature, peaceful way. The moment you try to address your grievances through violence, the moment you become intolerant of the beliefs and faiths of others, of their rights of action and thought, then you are on the wrong path and anybody who tries to do so must be stopped.

Q Are you looking forward to your next appointment to Phnom Penh?

A Yes. very much. It’s a very important part of the world for us and it promises to be a different kind of posting and I am quite sure I will enjoy it.

Q What will you miss about Turkey?

A I will miss the people. They are absolutely wonderful in the way they accept others into their society. They are very open-minded. I have made an extensive number of friends here and will miss them. I would like to come back again, at least as a tourist.

Human angle

Tolerance and beyond

by Prof Dr. Özer Ozankaya

“A thousand friends is too few, one enemy is too many,” declared our ancestors. The undesirability of any enmity among human beings could hardly be emphasised more strongly. Yunus Emre took up much the same theme 600 years ago: If you have broken someone’s heart once, it’s no prayer to God – this obeisance! To avoid breaking hearts, Yunus gives this advice: Be sure to look forward/ And remain faithful to your word/ Show tolerance to the created /For the Creator’s sake!

Tolerance! Many others have dwelt on the same theme at different times and places. It may be the very elusiveness of the virtue that has earned it so much attention. But there are no grounds for pessimism. A problem recognised is a problem half-solved. The more the intense need for tolerance is felt and voiced, the closer we come towards establishing a society based on it.

Today, the desire for an active, changing and developing society, rather than a stagnant one, is frequently expressed. But change is double-edged. What one person sees as progress may be another’s idea of regression. Social peace, unity and development can only coincide if the beauty of compromise is acknowledged.

How much tolerance?

Let us try to build a definition of tolerance. It is relevant to the personal behaviour of individuals on the one hand and to the actions of social authorities of all kinds on the other as they enact laws and lay down norms and rules. At both levels, it acknowledges that everyone should have the right to express opinions and beliefs, whether agreeable or not. It is both an attitude of mind and a rule of behaviour. The individuals and public authorities concerned need not abandon their views or refrain from expressing and defending them. But they do not prevent, by force or any other means, the peaceful statement of alternative positions.

Members of society enjoy equal rights, regardless of their ideas and attitudes. This is a basic ingredient of the Republic of Turkey and many other states – equality without any discrimination before the law, irrespective of language, race, political opinion, philosophical belief, religion and sect, or any such consideration. “We should not complain about the diversity of thoughts and beliefs,” argued Atatürk. “On the contrary, if all thoughts and beliefs meet at the same point, it will be a sign of inactivity.”

The question arises here whether it is appropriate to accord the freedom of expressions to those who, for their part, regard it as their right and duty to ensure the general adoption of their own way of thinking, even by force. For example, is it right to show tolerance to those who argue that democracy is irreligious and should be demolished, or who defend the dictatorship of the proletariat, and who advocate violence as a way of achieving such ends? I believe not. To allow the violent opponents of national sovereignty and democracy to organize, publish, demonstrate, train militants and receive finance is to wait with legs tied, like the sheep awaiting slaughter. This level of tolerance can be only an indication of incapacity.

Is tolerance enough?

As a concept, tolerance has its limits. Alongside its positive connotations, it can also imply an element of reluctance. For some, tolerance permits different beliefs and views to be regarded as inferior, even though they must be endured. The famous American economist John Kenneth Galbraith once recalled that as children their mothers told them to be tolerant towards Catholics, because they were “not good as we are”.

This example clearly illustrates the inadequacy of the concept of tolerance. If a person says, “Your beliefs or thoughts are of no value, so I choose to overlook and ignore them,” then the conclusion can be drawn that he or she would claim the right to suppress the assumptions and ideas in question if he or she regarded them as more consequential.

In summary, tolerance may incorporate politeness, pity and indifference. The reason why the concept of “freedom of thought” is distorted in many peoples’ minds is that acting politely or turning a blind eye are considered adequate. Whereas what is necessary is that every individual and authority should accept that people who hold different views from theirs are citizens with the same rights as themselves, respect them and act accordingly.

Mutual understanding

In the long term, a passive respect is not a sufficient condition for true social peace and integrity. On the contrary, it is also necessary to have an open mind, and to try to understand alternative ideas. That is to say, we should not maintain our beliefs and thoughts as they are, but we should revise them in the light of the beliefs and thoughts of others, and remain susceptible to further new influences.

The word tolerance fails to address this need. For hundreds of years, this concept was invoked in an effort to describe a virtue which is very difficult to put into practice. Today, too, there are selfish and vulgar persons and groups to whom a minimal tolerance can usefully be recommended, on the grounds that it is in their interests. That said, it is a difficult job to replace a word which has been useful in many ways, and which has been so much praised and exalted.

Tolerance is the minimum standard of behavior necessary for social peace and solidarity, and for the unity and integrity of nations. To turn a blind eye to beliefs and thoughts which differ from our own constitutes the lowest line which cannot be crossed. The goal to which our endeavours should be directed is displaying mutual respect and love and being ready to help each other in a positive way.

Science and democracy

Whatever you wish for yourself/ Wish the same for everyone else/ That, if anything, is the meaning/ Of all the sacred books, prescribed Yunus Emre. For him, too, tolerance was not enough: “Come near and let us meet- Even if we are strange, let’s love each other,” he wrote. How can this open-mindedness and mutual love and respect be achieved? The two most effective instruments are basing the administration of society on the principle of national sovereignty, and introducing a scientific manner of thought through education for persons of all ages. For both science and democracy are predicated on a free and equal tolerance.

Science requires devotion to the truth. It is an indispensable requirement of science to consider reality as it is without distortion, even if it is contrary to our beliefs and interests. From time to time, science tests its own knowledge. All findings are open to expert criticism. A scientist does not become angry with those who display the drawbacks of his or her theories, but is thankful for their comments. Compromise is connected with the respect shown by everyone for the truth – irrespective of creed, interest or habit. For this, it is essential to acknowledge the evidence of fact.

So it is in a genuine democracy. Democracy involves a search for the most widely acceptable solutions. Democracy has to be open to the free discussion of every citizen. This requires that facts should be available to the nation and not distorted or concealed. It requires that state officials should act in the knowledge that every citizen has to be served equally, no matter what their beliefs and opinions. An honest, impartial public administration is an indispensable requirement for social peace and national unity.

Just as, in science, there is no explanation or guide which is valid throughout space and time, so in democracy, there is no prescription, doctrine or command which can ensure the benefit of society in all eras and under all conditions.

Denizli message

In so far as public affairs are based on the twin principles (to quote Atatürk) that “Sovereignty is vested fully and unconditionally in the nation” and that “The real motto in life is science” , there can be no doubt that tolerance, mutual love and respect are intended. The strongest guarantee of national integrity and development, and hence of international peace, is that every citizen should learn and understand the implications of these principles. Are not these tenets, in fact, a modern composition of the following principles of virtue inscribed at the entrance to Denizli’s historic Babadağ Çarşı?

Show your love to all, greet them and don’t ignore them when they greet you;

Never discriminate, be just in giving all their due.

Always show goodwill, speak the truth on every occasion;

Never waver from good deeds, get along with everyone.

Spread friendship all around; good works will remain – you’ll be gone.

Know this well, and never forget it: Service comes first, then you’re gone!

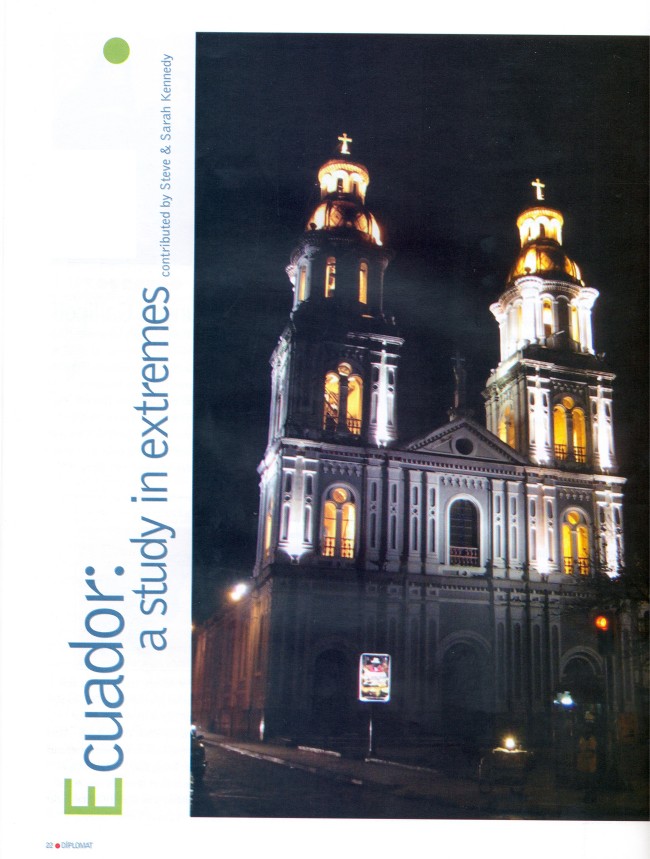

Ecuador: a study in extremes

by Steve & Sarah KENNEDY

Dwarfed by its neighbours Peru and Colombia, Ecuador makes up for what it lacks in expanse with the sharpness of its contrasts. And there are giants among its inhabitants…

By the standards of Latin America, Ecuador is a tiny country. But few 300,000 square-kilometre sections of the globe can boast such immense variety. The snow-covered peaks of the Andes are a world apart from the tropical rain forests of the upper Amazon, or the arid northern coast. Freezing mountain streams rub shoulders with hot volcanic spas. Mighty colonial cathedrals dominate run-down shanty towns. And in a famous group of islands off the coast, biodiversity takes on quite extraordinary dimensions.

High points

At 2,500 metres above sea-level, Quito makes Ankara (around 900m) seem a lowland plain. The world’s second highest capital city occupies a narrow plateau between high mountain ridges. Taxis and buses race around, groups of people stand or sit on the roadsides, and countless hawkers peddle bread rolls, sweets and chewing gum.

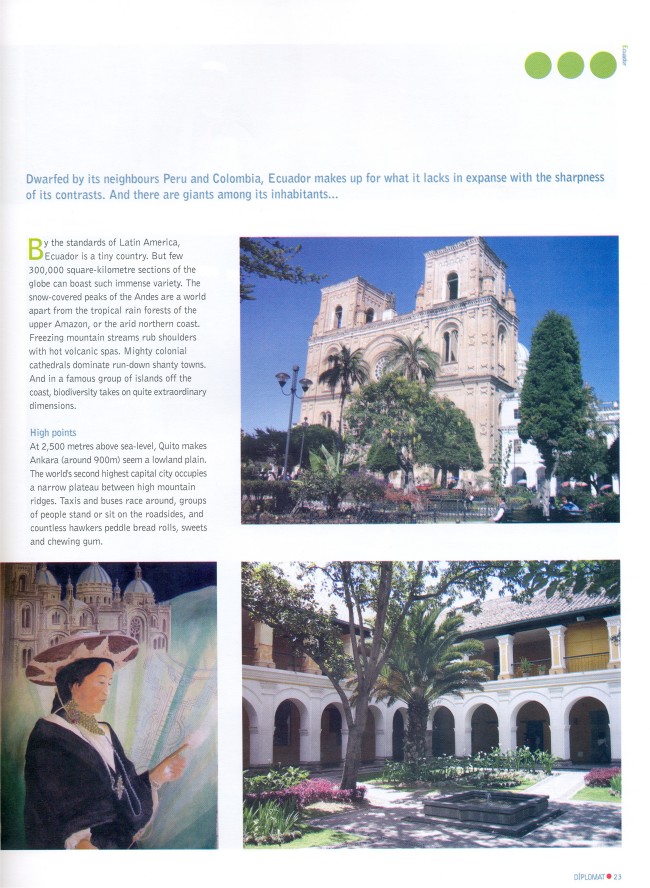

With its broad, cobbled squares, grand churches and vast Saint Fernando monastery, the old city centre is deservedly a UNESCO World Heritage site. If it is colonial charm you savour, head also for Cuenca to the south, where the thriving food and flower markets generate a sense of prosperity rarely evident on the streets of Quito.

Spring time

Ecuador’s architecture bears witness to a long and chequered history. Yet the constructions of humankind pale beside the legacy of geological time. The ridge of the Andes forms Ecuador’s spine, its ribs concealing a wealth of hot springs and spas.

A full 2,000 metres above the capital, the steam from the yellow, sulphuric pools of Papallacta rises to mingle with the misty rain, all but obscuring the looming volcanoes. This strangely relaxing experience comes at a price in comfort. After a tortuous 60km journey, the bus halts at the junction of an unsurfaced road and a dirt track, the visitors pile out into the rarefied air, and the last gasping 2km is negotiated on foot. Little wonder that urban Ecuadoreans prefer to take the waters at the pleasant town of Banos further south, a favourite weekend destination surrounded by natural spas.

Juicing up

Ecuador was so named by Spanish colonial settlers because it straddles the equator. Thirst, however, is unknown, thanks to the juices of myriad fruits on sale at bars, cafes and market stalls at all hours of the day. Mango, papaya, tree tomato… There are literally dozens of fruits rarely seen outside of South America, their names as exotic as their tastes.

Even breakfast begins with a large glass of fruit juice, followed by toast and eggs, and accompanied either by a mug of hot chocolate or by a (surprisingly poor) cup of coffee.

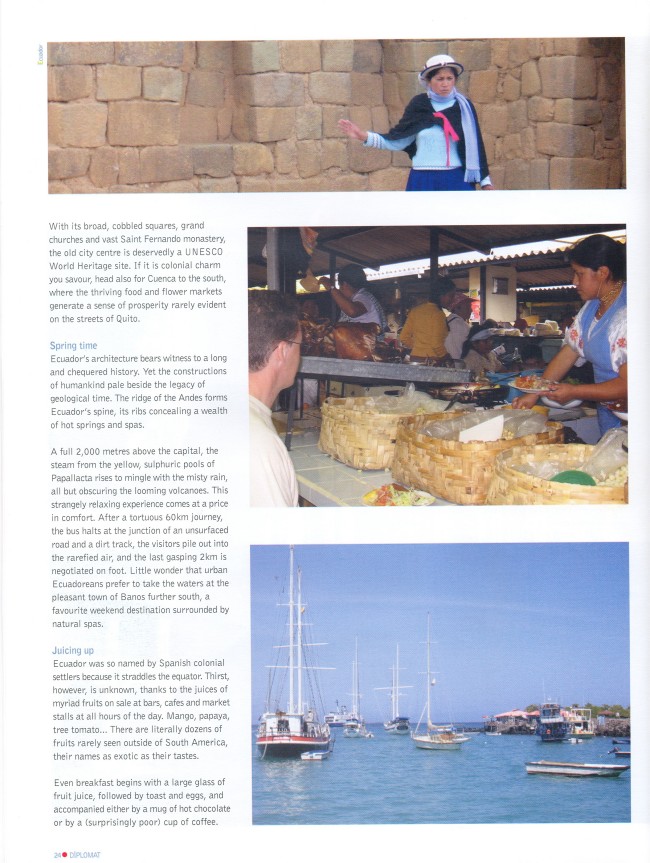

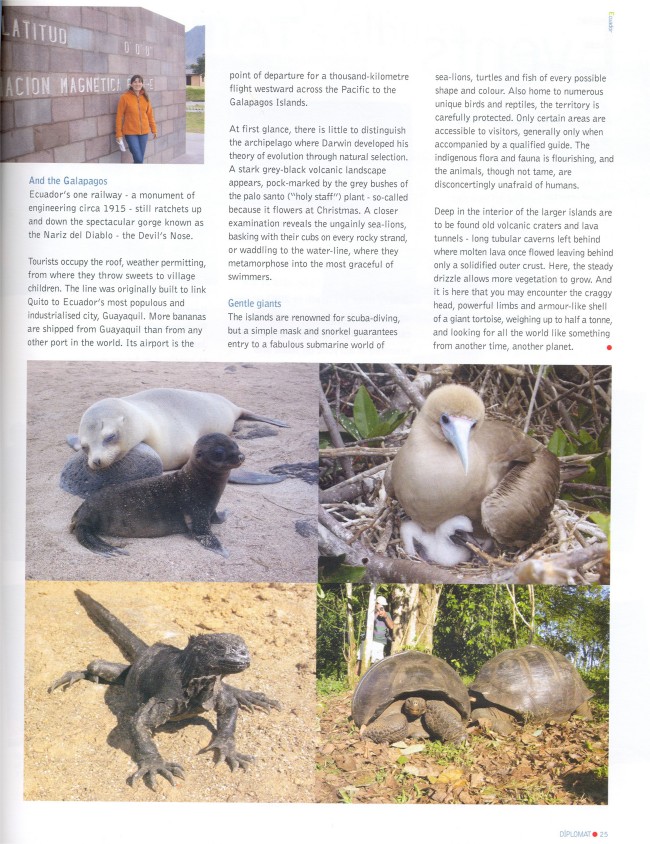

And the Galapagos

Ecuador’s one railway – a monument of engineering circa 1915 – still ratchets up and down the spectacular gorge known as the Nariz del Diablo – the Devil’s Nose. Tourists occupy the roof, weather permitting, from where they throw sweets to village children. The line was originally built to link Quito to Ecuador’s most populous and industrialised city, Guayaquil. More bananas are shipped from Guayaquil than from any other port in the world. Its airport is the point of departure for a thousand-kilometre flight westward across the Pacific to the Galapagos Islands.

At first glance, there is little to distinguish the archipelago where Darwin developed his theory of evolution through natural selection. A stark grey-black volcanic landscape appears, pock-marked by the grey bushes of the palo santo (“holy staff”) plant – so-called because it flowers at Christmas. A closer examination reveals the ungainly sea-lions, basking with their cubs on every rocky strand, or waddling to the water-line, where they metamorphose into the most graceful of swimmers.

Gentle giants

The islands are renowned for scuba-diving, but a simple mask and snorkel guarantees entry to a fabulous submarine world of sea-lions, turtles and fish of every possible shape and colour. Also home to numerous unique birds and reptiles, the territory is carefully protected. Only certain areas are accessible to visitors, generally only when accompanied by a qualified guide. The indigenous flora and fauna is flourishing, and the animals, though not tame, are disconcertingly unafraid of humans.

Deep in the interior of the larger islands are to be found old volcanic craters and lava tunnels – long tubular caverns left behind where molten lava once flowed leaving behind only a solidified outer crust. Here, the steady drizzle allows more vegetation to grow. And it is here that you may encounter the craggy head, powerful limbs and armour-like shell of a giant tortoise, weighing up to half a tonne, and looking for all the world like something from another time, another planet.

Speaking out

Ambassador Gazioğlu: 25 members – or 24½?

Diplomat opens its pages this month to Dr. Tamer Gazioğlu, the ambassador of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus to Ankara. Citing historical examples, Ambassador Gazioğlu emphasises that the international community and the Cypriots themselves have always officially recognised the existence of two separate peoples on the island, neither of which has the right to represent the other. Accordingly, he argues that the entry of one of the Cypriot parties – the Greek Cypriots – into the EU has created a Union not of 25 members but of 24-and-a-half. The ambassador also points out that it was the Greek Cypriots who refused to back the United Cyprus Republic foreseen in the Annan Plan while the Turkish Cypriots approved it. He blames this on the fact that the Greek Cypriots had already been assured of EU membership before the referendum.

In 1960, as a result of the 1959 Zurich and London Agreements, the “Republic of Cyprus” was established on a basis of equal partnership and bi-communality. Rights and responsibilities were shared by the two partners – i.e., the Turkish Cypriots and the Greek Cypriots – as well as the Guarantor States namely Turkey, Greece and the United Kingdom

Due to the Greek Cypriots’ everlasting desire for union with Greece, the Partnership Republic had to break up in 1963, which resulted in the isolation of the Turkish Cypriots from all organs of the Republic by force. In 1964, United Nations Peace Keeping Forces came to the island for the maintenance of the peace.

Peace talks between the Turkish Cypriots and the Greek Cypriots got under way in 1968, under the auspices and good offices of the UN, and continued until 1974 with the aim of restoring the partnership republic. But at the same time the Greek Cypriots proceeded with their campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Turkish Cypriot partner.

Bi-zonality affirmed

In 1974, the Greek junta instigated a coup d’etat in conjunction with the Greek Cypriot National Guard with a view to annexing the island to Greece. Thereupon, the Turkish Cypriots asked the Guarantor States of Cyprus to intervene and stop the genocide which the Greeks and Greek Cypriots were implementing widely against the Turkish Cypriot people. To this call for help, only Turkey responded. Invoking her rights deriving from the Treaty of Guarantee, Turkey intervened in Cyprus on July 20, 1974, to end the killings and make possible reconciliation.

The principles of bi-zonality and bi-communality were affirmed with the Exchange of Populations Agreement signed in Vienna in 1975, accommodating the Turkish Cypriots in the north of the island and the Greek Cypriots in the south.

Intercommunal talks began with the 1977 Summit Meetings between Rauf Denktaş and Archbishop Makarios, and resumed in 1979 between Denktaş and Spyros Kyprianou. It was agreed that a solution should be based on a bi-communal and bi-zonal federal structure with two administrations.

From De Cuellar to Annan

In his report on the Summit Meetings, H.E. Mr. Perez de Cuellar, the Secretary-General of the UN ad-interim, stated that the envisaged federal republic would comprise the Turkish Cypriot community and the Greek Cypriot community with separate provinces or federated states.

Resolution 649, adopted by the UN Security Council on March 12, 1990, called upon the leaders of the two communities “to pursue their efforts to reach a mutually acceptable solution providing for the establishment of a federation that will be bi-communal as regards the constitutional aspects and bi-zonal as regards the territorial aspects…”

When the succeeding UN Secretary-General, H.E. Mr. Boutros B. Ghali, put forward the “Set of Ideas” as a formula for a solution, he too underlined that a solution should be based on a federal structure formed by two communities, two regions and two administrations.

The comprehensive settlement plan initiated by UN Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Kofi Annan in 2002 was strongly supported by the members of the UN as well as the 15 EU member states. According to the Plan, there existed in Cyprus two constituent states – namely the Turkish Cypriot Constituent State and Greek Cypriot Constituent State.

2004: separate referenda

As history has shown, this Plan was bound to fail since the Greek Cypriot side was privileged with EU membership, whether or not a solution was reached to the Cyprus problem.

The Annan Plan foresaw – and both of the parties consented to this – that the Plan should be submitted to separate referenda among the two Cypriot sides as a condition for its adoption. The referenda were held on April 24, 2004, and resulted in 76% of the Greek Cypriots voting against the Plan, while an overwhelming 65% of the Turkish Cypriots cast their votes in favour of the Plan and in support of a peaceful settlement in Cyprus. The fact that separate referenda were held is indicative of the fact that there are on the island two separate peoples with separate administrations, and that neither has the right to represent the other or act on its behalf.

On May 1, 2004, the Greek Cypriot administration acceded to the EU, regardless of the fact that it only represents the Greek Cypriot people and hence only part of the island. The part of the island which the Greek Cypriot administration represented, moreover, was the side which had rejected a solution that would have permitted the unification of the island under the banner of a “United Cyprus Republic”.

Rewards and punishments

On May 28, 2004, Kofi Annan stated in his report on the developments that “The Turkish Cypriot vote has undone any rationale for pressuring and isolating them”. He called on the Security Council to support cooperation with the Turkish Cypriots and to eliminate unnecessary restrictions and barriers which isolate the Turkish Cypriots.

Speaking in Brussels on December 17, 2004, Secretary-General Kofi Annan stated: “We had hoped, it (Cyprus) would have entered the (European) Union as a unified state. We didn’t make it but there is a tomorrow” (Turkish Daily News, December 18, 2004)

It is an undeniable fact that there exist two separate peoples on the island whose future should be based on a lasting peace and a viable partnership. The Turkish Cypriot party affirmed its willingness to reach a solution and displayed a political desire for unification in accordance with the Annan Plan. It should not be punished for the “No” vote of the other party. The Turkish Cypriots should instead be rewarded with greater commitments internationally.

How many members?

In the light of the facts and realities mentioned above, it is apparent that the European Union presently has 24-and-a-half member states, since there are two distinct peoples and two separate administrations in the island, and the Greek Cypriot Administration does not in any way represent or have any authority over the Turkish Cypriot people.

It is therefore of utmost importance that the EU, and the rest of the international community, in order to eliminate this awkward situation, should encourage a comprehensive and lasting solution of the problem under the auspices of the UN and its good offices, rather than treating the Greek Cypriot Administration as the “government of the whole of Cyprus” – an approach which only encourages the Greek Cypriot party to maintain its intransigency. Otherwise, the case of Cyprus will be a case of half-membership, and the EU will be composed of 24½ member states.

Philately

Turkey’s first Postal Stationeries

by Kaya DORSAN

Materials such as cards and envelopes with stamps printed on them by the Post Office are known to philatelists as Postal Stationery.

The use of this type of material in postal services is as old as the history of stamps. In Turkey, the first postal stamp was used in 1863, while the first envelope with a stamp printed on it was put on sale in 1869. In line with the custom at the time, the stamp was not printed on the front of the envelope but on the reverse, like a seal. Issued in three different values, these envelopes were the first Turkish postal stationery printed by the Ottoman Post Office.

Postcards and bands

The first postcard with a postal stamp printed on it was issued in 1877. This card, which cost 20 para, carries texts in Ottoman and French. It was so popular that new postcards were subsequently put on sale every three or four years.

“Double post cards” went on sale for the first time in 1881. Each double card consisted of a set of two cards, one of which was to be used by the sender, and the other of which was provided for the receiver to reply. Cards of this type continued to be used in Turkish postal services up to the 1950s.

The creation of the first “letter-cards” in 1895 was followed in 1901 by the issue of the first “newspaper wrappers”. These long paper bands with stamps pre-printed on them simplified the posting of newspapers.

The first aerogramme

The first registered postal envelopes were used in 1914. These envelopes were printed in three different sizes in order to carry various valuable documents by registered post.

The postal Stationery tradition continued after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. In 1963, the aerogramme was put on sale for the first time.

Aerogrammes are made from thin paper, so as to be very light. One side is written on, and the paper is then folded to take the form of an envelope. The aerogrammes were printed with three different prices for internal mail, foreign mail and mail to distant countries.

Collecting postal stationery is one of the most enjoyable aspects of the philatelist’s endeavours.

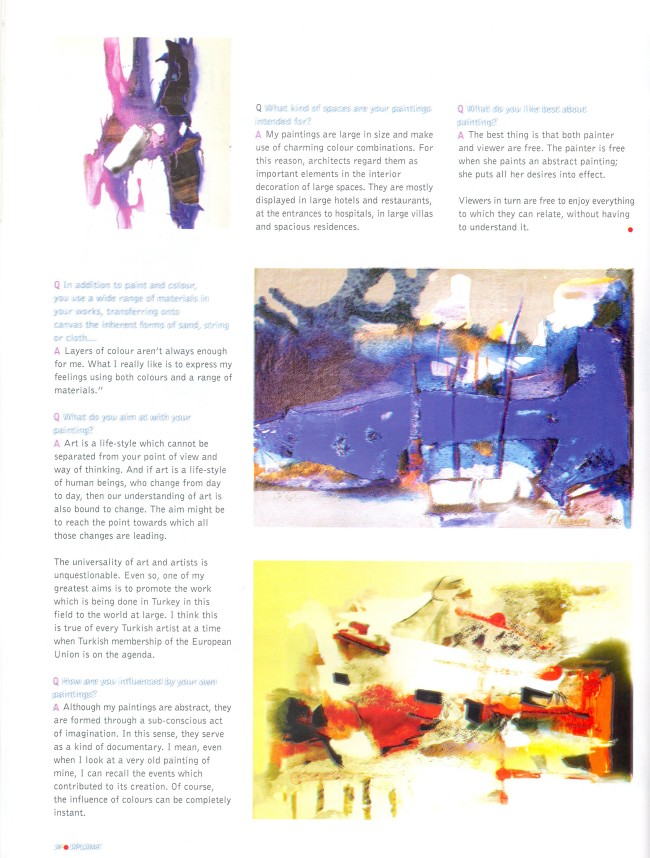

Arts

Nazan Günay’s dance with colour

by Recep Peker TANITKAN

The colours dance or struggle with one another, driving you from storm to storm, then on to peace and calm. You can only be looking at the works of Nazan Günay. Diplomat profiles the artist and her work.

When it comes to colour, Nazan Günay has no inhibitions. All the colours of the rainbow appear on her canvases. Sometimes they dance and sweep you off your feet; sometimes they wrestle with one another, setting off storms within your mind. At times they are so gripping that it becomes difficult to distinguish one colour from another within the vivid display.

The artist’s colours speak clearly of her inner world, reflecting her joy, her contentment, her darker moods. The paintings patently take shape beyond her consciousness. At tranquil moments, greens and blues appear. But as a woman of the 21st century, Günay has many things to create, and her creativity is generally brought to life in myriad bright tones. We asked her a palette of questions:

Q How would you describe your style?

A It would be more correct to say that my paintings are abstract. While there are many artistic currents, paintings can generally be classified as either figurative or abstract. Mine would count as abstract. In recent paintings, I have made use of figures, but basically I use them as an element of abstract painting. I mean, they are a form like any other.

Q Which colours enchant you most?

A I mostly use warm colours in my paintings. But I would argue that a work of art is formed by contradictions. So I make sure that there cold greys beside my bright warm colours. The colours which enchant me are purple, orange, pink, turquoise, green and red.

Q In addition to paint and colour, you use a wide range of materials in your works, transferring onto canvas the inherent forms of sand, string or cloth…

A Layers of colour aren’t always enough for me. What I really like is to express my feelings using both colours and a range of materials.”

Q What do you aim at with your painting?

A Art is a life-style which cannot be separated from your point of view and way of thinking. And if art is a life-style of human beings, who change from day to day, then our understanding of art is also bound to change. The aim might be to reach the point towards which all those changes are leading.

The universality of art and artists is unquestionable. Even so, one of my greatest aims is to promote the work which is being done in Turkey in this field to the world at large. I think this is true of every Turkish artist at a time when Turkish membership of the European Union is on the agenda.

Q How are you influenced by your own paintings?

A Although my paintings are abstract, they are formed through a sub-conscious act of imagination. In this sense, they serve as a kind of documentary. I mean, even when I look at a very old painting of mine, I can recall the events which contributed to its creation. Of course, the influence of colours can be completely instant.

Q What kind of spaces are your paintings intended for?

A My paintings are large in size and make use of charming colour combinations. For this reason, architects regard them as important elements in the interior decoration of large spaces. They are mostly displayed in large hotels and restaurants, at the entrances to hospitals, in large villas and spacious residences.

Q What do you like best about painting?

A The best thing is that both painter and viewer are free. The painter is free when she paints an abstract painting; she puts all her desires into effect. Viewers in turn are free to enjoy everything to which they can relate, without having to understand it.

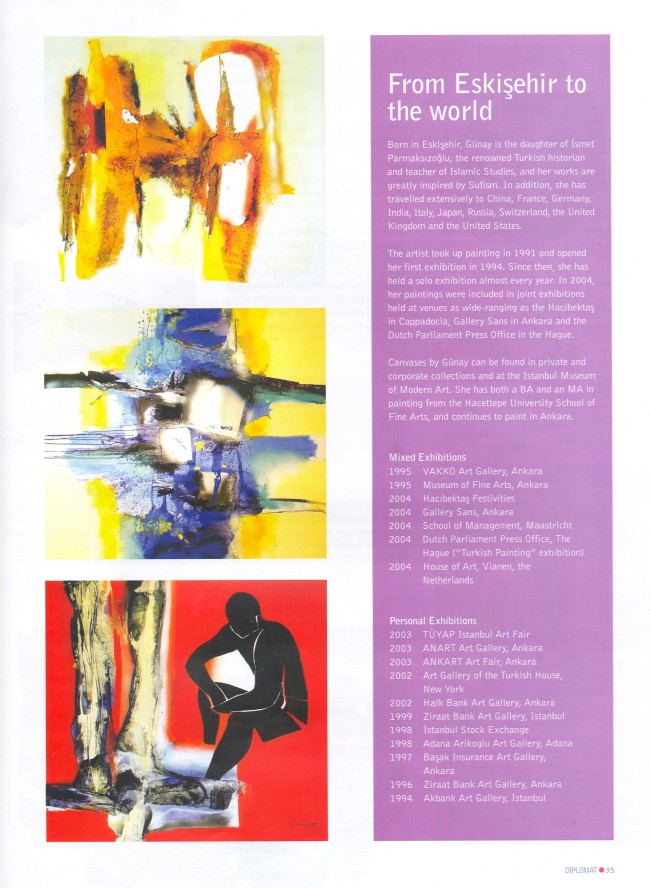

From Eskişehir to the world

Born in Eskişehir, Günay is the daughter of İsmet Parmaksızoğlu, the renowned Turkish historian and teacher of Islamic Studies, and her works are greatly inspired by Sufism. In addition, she has travelled extensively to China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The artist took up painting in 1991 and opened her first exhibition in 1994. Since then, she has held a solo exhibition almost every year. In 2004, her paintings were included in joint exhibitions held at venues as wide-ranging as the Hacibektaş in Cappadocia, Gallery Sans in Ankara and the Dutch Parliament Press Office in the Hague.

Canvases by Günay can be found in private and corporate collections and at the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art. She has both a BA and an MA in painting from the Hacettepe University School of Fine Arts, and continues to paint in Ankara.

Mixed Exhibitions

1995 VAKKO Art Gallery, Ankara

1995 Museum of Fine Arts, Ankara

2004 Hacıbektaş Festivities

2004 Gallery Sans, Ankara

2004 School of Management, Maastricht 2004 Dutch Parliament Press Office, The Hague (“Turkish Painting” exhibition)

2004 House of Art, Vianen, the Netherlands

Personal Exhibitions

2003 TÜYAP Istanbul Art Fair

2003 ANART Art Gallery, Ankara

2003 ANKART Art Fair, Ankara

2002 Art Gallery of the Turkish House, New York

2002 Halk Bank Art Gallery, Ankara

1999 Ziraat Bank Art Gallery, Istanbul

1998 Istanbul Stock Exchange

1998 Adana Arikoglu Art Gallery, Adana

1997 Başak Insurance Art Gallery, Ankara

1996 Ziraat Bank Art Gallery, Ankara

1994 Akbank Art Gallery, Istanbul

Aydın: cities of ancient times

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

Home to the seaside resort of Kuşadası, and rich in cotton, tobacco, olives and fruit, the province of Aydın has played a vital role in the modern Turkish economy, contributing significantly to the development of Izmir to the north and Bodrum to the south. Blessed with fertile soils and a benign climate, the region was also a major crossroads of civilisation in earlier millennia. Our travel correspondent has been delving into the past of a province with more than its share of ancient sites. Here, he offers glimpses of six of Aydın’s historic cities.

For peering into the past, there are few better vantage points. Prehistoric traces suggest that Aydın has been a centre of population ever since human beings first came to live in settlements. The earliest written records date from the time of the Hittites. These sources speak of a river called Seha which watered a valley in the west – almost certainly a reference to the Büyük Menderes. The territories to the north of the Seha were known as Lukka – a word which was to re-emerge in later history when the Lycians settled in the Teke Peninsula to the south. Somewhere in the west of the district, there was a place called Ahiyyawa. From the yearbooks of Hittite King Mursil II (1340-1309 BC) and other Hittite sources we ascertain that in those far-off times Ephesus was known as Apasa, Milet as Milavanda, Priene as Pariyana, Alinda as Ilyalanda and Alabanda as Walivanda. Remarkably, we also learn that Aphrodisias was formerly known as Ninoe – a name which points to a connection with Mesopotamia.

Cradled in the dawn of history, these settlements grew and multiplied as various peoples arrived, either by sea or by land, to make their homes along the Aegean coast. The northern tribes which emigrated from Thrace to Western Anatolia in the 7-8th century BC soon populated the inner parts of Western Anatolia and the Menderes Valley. They established Nysa, Magnesia and other cities, and restored Aydın, the present provincial centre, formerly known as Atria. Then came the age of empire – Persian, Alexandrian, Seleucian and Roman. Key dates include 400 BC, when the Spartans made an unsuccessful attempt to wrest control of Aydın and its surroundings back from the Persians, 334 BC, when Alexander the Great succeeded overcame the Persians and turned the region into a base, and 190 BC, when the Romans placed Aydın under the rule of King Eumenes of Bergama (Pergamum, Pergamon). The following paragraphs offer a brief guide to the region’s ancient urban gems.

The rise and fall of Aphrodisias

Its well-preserved, monumental buildings and its association with Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, have made Aphrodisias, in the Karacasu district, one of Turkey’s most important archaeological sites. The temple of Aphrodite was already famous in Roman times. In fact, the history of the settlement is much older. A tumulus, later decorated by a theatre, provides evidence of a prehistoric settlement dating back to 5000 BC. And the first temple of Aphrodite was constructed in the 6th century BC, when Aphrodisias was still a little village. The appearance of the settlement changed completely in the 2nd century BC, with the establishment of a grid planned-city. By this time, the city had spread over a square kilometre and was home to some 150,000 people.

In the first century BC, the Roman Emperor Augustus took Aphrodisias under his personal protection. The monuments which fascinate the visitor today were built over the following two centuries. Between the Theatre and the Temple, two public squares were laid out, each surrounded by columns. In the northern part of the city stood the stadium, now the best-preserved stadium of the ancient world. Towards the end of the 3rd century AD, Aphrodisias became the capital of the Roman province of Caria. In the middle of the 4th century, the city was surrounded by ramparts. But in the 6th century its importance began to dwindle. The Temple of Aphrodite was converted into a church. Reduced to a small town, the city was abandoned altogether in the 12th century.

Divided city of Nysa

Another of the cities of Caria, Nysa, is to be found within the borders of the Sultanhisar district. Substantial information about the city is provided by the ancient historian Strabon, who lived most of his life in Nysa. As Strabon explains, the city consisted of two parts divided by a flood-prone area.

The Gymnasium is situated in the western part of the city. Further north are to be found a library and the ruins of some Byzantine buildings. The two-storey Roman era library is the best-preserved in Turkey with the exception of the Celsus Library in Ephesus. To the north of the library stands a theatre. Historians and artists are particularly attracted to the reliefs of the stage building.

East of the flood zone are the odeon (concert hall) and bouleuterion (assembly room). The necropolis is situated on the road to Akharaka, a small settlement to the west.

Tralleis today

Aydın, today’s provincial centre, is a city of many names. It was known as Ceasarec until the end of the Nero era, but in the first century AD it was redesignated Tralleis – an appellation which first occurs, in the form of Tralli, in the writings of Xenophon. Today, the ruins of Tralleis can be found on a trapezium-shaped hill called Topyatağı in the north of Aydın central district.

The first of the monumental buildings whose ruins are visible today were constructed under the Bergama Kingdom. During the Hellenistic and Roman eras, the city occupied an important location on the border between the provinces of Caria and Lydia. In 129 BC it was annexed to the Asia province of the Roman Empire. For four years from 88BC onwards, in the wake of the revolt of King Mithridates Eupator of Pontus against the Roman Empire, it was administered by Pontus

Initial research was carried out by Ch. Texier and Ch. Felows in the 19th century, and the first excavations were carried out by a German team headed by Von Kaufmann and directed by C. Humann and W. Dörpfeld in 1889. Like Aphrodisias, Tralleis turned out to have been built on an earlier settlement – the first residents lived in the Deştepe tumulus in Dedekuyusu 6,500 years ago. There are few remaining artefacts from the ancient era, but the works of art which survived the major earthquake in 1898 are exhibited in Aydın Museum and Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Legend of Magnesia

The ruins of the ancient city of Magnesia are to be found in the village of Tekinköy in Ortaklar in the district of Germencik, on the Ortaklar-Söke highway. According to legend and ancient sources, the city was established by a tribe memorably known as the Magnets, who arrived in the area from Thesselia. Led by Leukippos and guided by an oracle of Apollo, the Magnets landed on the shore of what is now Lake Bafa but which at the time was an arm of the Aegean. The location of the original city of Magnesia is not known, although it is understood to have been located on the banks of the Menderes.

Magnesia occupied a significant location, commercially and strategically, within the triangle of Priene, Ephesus and Tralleis. The first excavations in the region were carried out by Carl Humann on behalf of the Berlin Museum in 1891. Excavations lasted for 21 months and brought to light a theatre, a temple of Artemis with an altar, a temple of Zeus and a prytaneion, or city hall. Artefacts found in Magnesia are exhibited in museums in Paris, Berlin and Istanbul. Nearly 100 years later, in 1984, a team headed by Prof. Orhan Bingöl resumed work at the site on behalf of the Ministry of Culture and Ankara University.

The Miletus monuments

Milet offers one of Aydın’s more spectacular and diverse collections of ruins. Under its ancient name of Miletus, the city was an important Mycean colony and a highly developed cultural and commercial centre in the mid-2nd century BC. It maintained its reputation during the Roman era but lost its commercial importance with the clogging of the Gulf of Latmos in Byzantine times. In the 13th century, Milet was turned into Balat by the Menteşe dynasty, and enjoyed another illustrious moment in history as the capital of Menteşeoğulları.

The first historic buildings to come into view as one advances along the Söke-Milet road are the theatre and the Byzantine castle. In addition to the theatre, the caravanserai, the Faustina Baths, the İlyas Bey Mosque, the Temple of Serapis, the bouleuterion, the Holy Road, the Ionic stoa building, the North Agora, the Delphinion (temple of Apollo), the harbour gateway, the Church of St. Michael and the Heroon (monumental tomb) are also well worth seeing.

The temple at Didim

Didymaion, now known as Didim, was once one of the most significant holy places of the region and a major centre of Apollonian soothsaying. Situated on the coast 55 km away from the district centre of Söke, its temple was demolished by the Persians when they attacked Miletus in 494 BC. Following his victory over the Persians, Alexander the Great determined to build a much larger temple. Construction work began in 300 BC and continued for several decades. Although the work was never completed, the temple was the third biggest in the world at the time, following the Temple of Artemisis at Ephesus and the Heraion in Samos.

Measuring 60m by 118m, the temple was set on a platform surrounded on four sides by flights of seven steps. At the eastern entrance, there are 13 steps. The building is surrounded by two lines of columns. There are 124 columns each 19.7m tall.

Figs: ancient, sacred fruit

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

Figs continue to thrive in the perfect soils and climate of Aydın, where they have been regarded as sacred since time immemorial.

Figs are grown in many parts of the Aegean and beyond, but Aydın is universally regarded as their homeland. Renowned for their thin peel, their small stones, their honeyed flesh and their pleasing aroma, the figs of the province are also highly suitable for drying. Though sweet, they do not easily crystallize, and when it comes to size, it sometimes takes only three to make up a kilo. Figs from Aydın – known locally by the name yemiş as well as the more familiar incir – command the best prices from Turkish shoppers, and among international dealers they are without rival.

What makes these exotic fruit so special that they and Aydın have become virtually synonymous? What sets them apart from figs cultivated in other regions? The fertile soils of the province, responds the geographer – its perfect climate and humidity, and the ripening influence of the wind. Since ancient times, adds the historian, the fig and the fig leaf have symbolised power and peace. Blessed by Aydın’s ancient civilisation, these fruit have never lost their sacred qualities. Today they are exported dried to Christian countries before Christmas and to Muslim countries in the spring-time.

Harvest time

To Aydın folk, a fig is not simply a fig. Each fruit is classified by quality into one of numerous varieties – Sarılop, Göklop, Sofralık, Bardacık and Karayaprak to name a few. The Sarılop and Göklop figs are particularly suitable for drying.

As the figs start to sweeten during August, they are collected and left to dry in specially-prepared clearings set aside for the purpose within the orchards, known as incir harmanı – literally, the “fig harvest”. They are then grouped according to their size and colour. Those that are large, white, and spotless are chosen first, while those that are darker, cleft, spotty or smaller ones are classed as naturel. Figs which do not make the grade at all are referred to as hurma and – so as not be wasted – are generally used in the manufacture of methylated spirits.

Tailleurs: nostalgic and new

by Sibel DORSAN

The jacket-and-skirt or jacket-and-trousers combination you are wearing is not to be taken for granted. Revolutionary in the past, it has been evolvıng for almost a century and continues to rejuvenate itself in fresh forms each season.

The female two-piece suit or tailleur has been enjoying another golden year. The combination of jacket over skirt or trousers has rarely, indeed, been out of fashion, showing an endless capacity to reinvent itself – casual or business-like, unisex or unrepentantly feminine – in the hands of the famous fashion houses. It is also set to take on new connotations in summer 2005.

The tailleur was first inspired by male fashion at the end of the 19th century. Its simple style and practicality contrasted sharply with the imposing and uncomfortable clothes worn by women at the time, and it perfectly reflected the spirit of an age when women in the West were struggling for equality and political rights.

Conservative society was shocked, but social rules were eventually to bend and break, and women-in-jackets were to become a familiar and unquestioned sight. At the end of World War I, the tailleur gained an indispensable place in the world of fashion. Soon it came to symbolize the 1920s androgen image.

Return of the feminine

It was in France that the two-piece initially conquered the fashion world, so it was only proper that it should be given a new lease of life in the simple and comfortable designs of Chanel. A symbol of women’s independence, it now also proved that freedoms did not have to come at the expense of femininity.

When it first began to dominate the collections of the grands ateliers of Chatel and Patou, the tailleur was regarded as a casual costume worn for travel or holidays. But before long, the two-piece had come to symbolize smartness at every hour of the day.

Jackets, worn in various lengths from the waist to the thigh, had at first merely imitated male jackets. But the new suits departed from the strict designs of the 1930s. They were worn primarily as evening wear and for ceremonial occasions. The jackets were long, fitted and embroidered, and sported broad padded shoulders and colored buttons made of jewels. This was the baroque period of the tailleur.

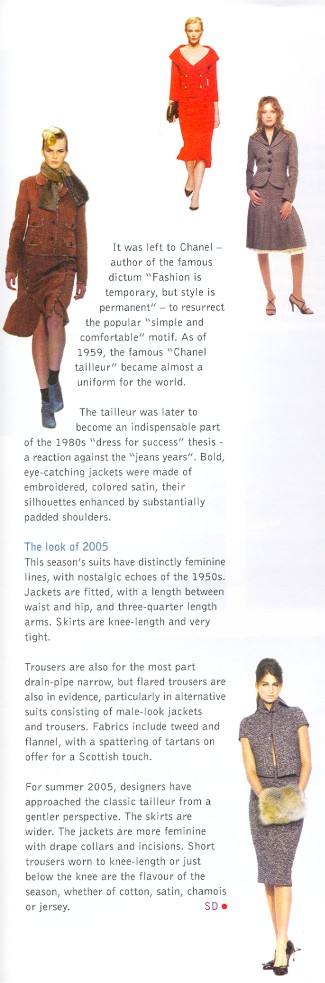

From the ‘50s to the ‘80s

Two-pieces of various cuts and lengths remained popular throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The unique styles of Dior and Balmain added a catchier look. Jackets made of quality fabric, gathered at the waist and embracing the body like a corset, made an indelible impression. It was left to Chanel – author of the famous dictum “Fashion is temporary, but style is permanent” – to resurrect the popular “simple and comfortable” motif. As of 1959, the famous “Chanel tailleur” became almost a uniform for the world.

The tailleur was later to become an indispensable part of the 1980s “dress for success” thesis – a reaction against the “jeans years”. Bold, eye-catching jackets were made of embroidered, colored satin, their silhouettes enhanced by substantially padded shoulders.

The look of 2005

This season’s suits have distinctly feminine lines, with nostalgic echoes of the 1950s. Jackets are fitted, with a length between waist and hip, and three-quarter length arms. Skirts are knee-length and very tight. Trousers are also for the most part drain-pipe narrow, but flared trousers are also in evidence, particularly in alternative suits consisting of male-look jackets and trousers. Fabrics include tweed and flannel, with a spattering of tartans on offer for a Scottish touch.

For summer 2005, designers have approached the classic tailleur from a gentler perspective. The skirts are wider. The jackets are more feminine with drape collars and incisions. Short trousers worn to knee-length or just below the knee are the flavour of the season, whether of cotton, satin, chamois or jersey.

Cunda: the complete island

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

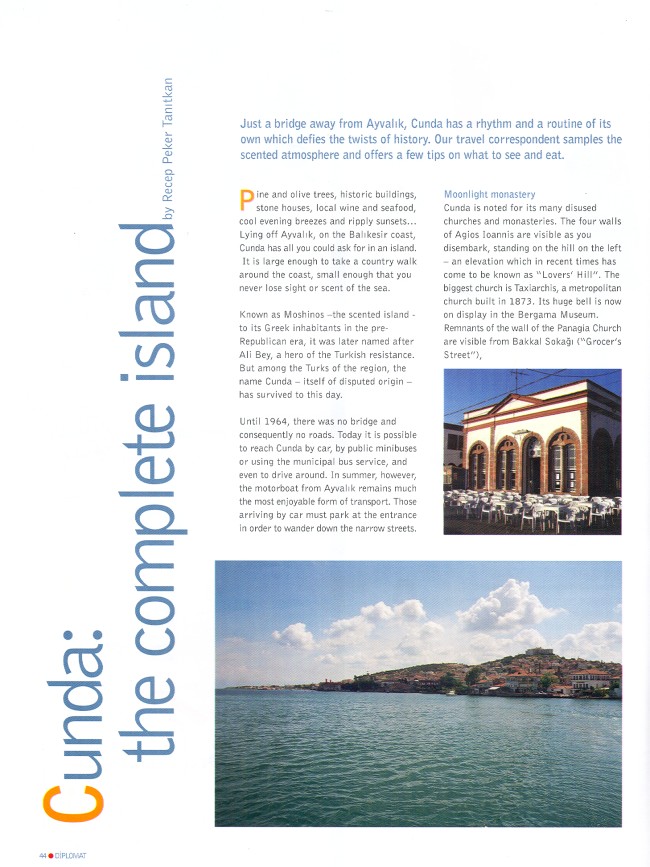

Just a bridge away from Ayvalık, Cunda has a rhythm and a routine of its own which defies the twists of history. Our travel correspondent samples the scented atmosphere and offers a few tips on what to see and eat.

Pine and olive trees, historic buildings, stone houses, local wine and seafood, cool evening breezes and ripply sunsets… Lying off Ayvalık, on the Balıkesir coast, Cunda has all you could ask for in an island. It is large enough to take a country walk around the coast, small enough that you never lose sight or scent of the sea.

Known as Moshinos –the scented island – to its Greek inhabitants in the pre-Republican era, it was later named after Ali Bey, a hero of the Turkish resistance. But among the Turks of the region, the name Cunda – itself of disputed origin – has survived to this day.

Until 1964, there was no bridge and consequently no roads. Today it is possible to reach Cunda by car, by public minibuses or using the municipal bus service, and even to drive around. In summer, however, the motorboat from Ayvalık remains much the most enjoyable form of transport. Those arriving by car must park at the entrance in order to wander down the narrow streets.

Moonlight monastery

Cunda is noted for its many disused churches and monasteries. The four walls of Agios Ioannis are visible as you disembark, standing on the hill on the left – an elevation which in recent times has come to be known as “Lovers’ Hill”. The biggest church is Taxiarchis, a metropolitan church built in 1873. Its huge bell is now on display in the Bergama Museum. Remnants of the wall of the Panagia Church are visible from Bakkal Sokağı (“Grocer’s Street”),

Of the eight monasteries known to have been founded on the island, the most famous is Agios Dimitrios Ta Selina, meaning Moonlight. Understood to be over 200 years old, its remains form an unusual silhouette at the end of an earthen track on an arm of the island jutting out into the sea to the North.

Another well-known local landmark is the famous Taş Kahve – or “Stone Coffee Shop”. With its inviting sea-front façade, its coloured windows and high ceilings, it has an atmosphere all of its own, and a tea break here is an essential part of any visit to Cunda. Both Cunda itself and Ayvalık offer pleasant hotels and attractive boutique guest houses for visitors wishing to spend the night.

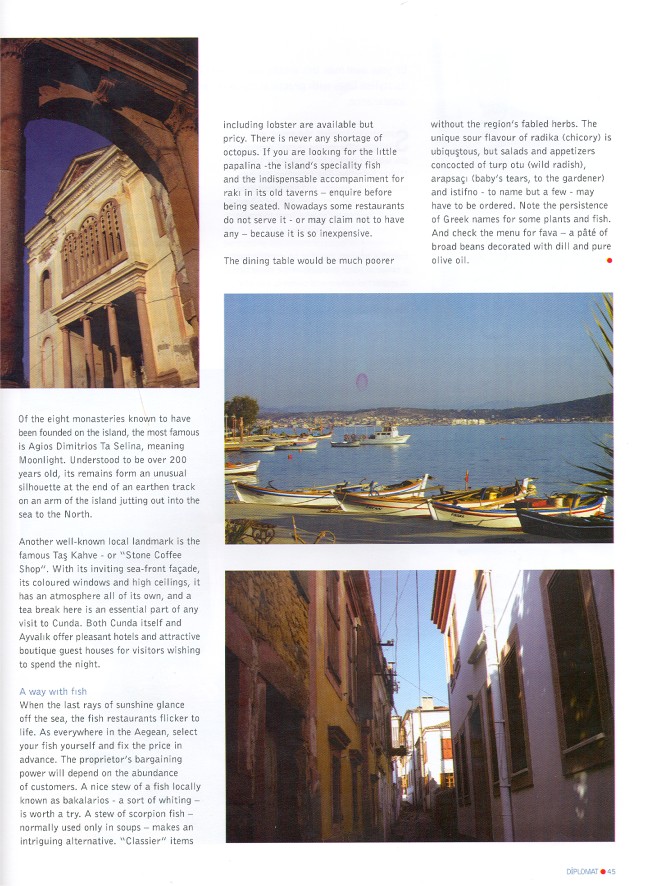

A way with fish

When the last rays of sunshine glance off the sea, the fish restaurants flicker to life. As everywhere in the Aegean, select your fish yourself and fix the price in advance. The proprietor’s bargaining power will depend on the abundance of customers. A nice stew of a fish locally known as bakalarios – a sort of whiting – is worth a try. A stew of scorpion fish – normally used only in soups – makes an intriguing alternative. “Classier” items including lobster are available but pricy. There is never any shortage of octopus. If you are looking for the little papalina – the island’s speciality fish and the indispensable accompaniment for rakı in its old taverns – enquire before being seated. Nowadays some restaurants do not serve it – or may claim not to have any – because it is so inexpensive.

The dining table would be much poorer without the region’s fabled herbs. The unique sour flavour of radika (chicory) is ubiqutous, but salads and appetizers concocted of turp otu (wild radish), arapsaçı (baby’s tears, to the gardener) and istifno – to name but a few – may have to be ordered. Note the persistence of Greek names for some plants and fish. And check the menu for fava – a pâté of broad beans decorated with dill and pure olive oil.

Kocatepe: Ankara’s dissonant monument

by Bernard KENNEDY

Although formally opened in 1987, Ankara’s dominant Kocatepe Mosque has yet to shrug off the latent controversies which surrounded its construction and its design. One consequence is that its exterior is much more familiar than its interior.

Arguably the most prominent feature of the Ankara skyline, Kocatepe Mosque is certainly the most frequently wished away. Nineteen years after its long-delayed completion, it remains, in the eyes of many citizens, an affront to a city previously dominated by civic buildings and national monuments. Aside from the commercial basement supermarket and car park, it pretends to be nothing other than a concrete copy of the famous 15th and 16th century mosques of Istanbul. Its vast dome – 25.5 metres in diameter – and deliberate Ottoman lines are perceived as a pay-back for early Republican secularism.

Awesome proportions

Such heavy recriminations may mystify newcomers or ordinary folk, for whom an Ankara evening is now difficult to imagine without the flood-lit triple balconies of Kocatepe’s minarets. Besides featuring prominently on Ramadan TV shows, the mosque has assembled its own congregation – although it has rarely reached its 20,000 capacity – and funeral ceremonies are increasingly held here as well as at the traditional venues, Hacı Bayram and Maltepe.

Kocatepe lacks a clear approach in most directions, and its outer structures already peel and leak. From the courtyard onwards, the walls are enriched with marble, while the leaden domes and half-domes are bordered with gold and copper-leaf. Inside, the massive pillars and open spaces boast the same awesome proportions as any Ottoman masterpiece, but the atmosphere is lighter and airier and the constantly hoovered carpets are all of one colour and design.

Golden chandelier

Doors, windows and the peripheral staircases leading to the women’s area are decorated in traditional geometric patterns. In a glass showcase stands a model of the Mescid-i Nebevi in Medine – a gift to President Süleyman Demirel from King Fahd of Saudi Arabia. But the eye is drawn upwards to giant brass inscriptions and to a mass of intricate paintwork that bears comparison with any painstaking Istanbul restoration, soaring up past serpentine galleries towards the 48.5-metre zenith.

Most striking of all, is the huge, low spherical chandelier, a golden invocation of sun, moon and stars – or so it seems – surrounded by multiple miniature replications. Beyond the marble niche and pulpit, the day filters in through bright stained glass windows above a blue-tiled wall.

Genuine treasures

Kocatepe’s sheer size and its innovative sources of light merit some curiosity. But if they travel to the capital at all, mosque buffs may be forgiven for seeking out instead a cluster of genuine Seljuk treasures in and around Ulus. The Hacı Bayram – long Ankara’s central mosque – attracts sight-seers with its views and its site adjoining the ancient Temple of Augustus as well as its 15th, 16th and 18th century artisanship. Less well known but also worth a visit is the early Ottoman single-domed New Mosque at Ulucanlar, East of the citadel.

Tale of two cities

If a mosque was to be built at all on the once-grassy elevation where children played in decades past, could it not have been a building more in keeping with Ankara’s modernizing claim? The architectural project originally selected for Kocatepe is generally assumed to have fulfilled this specification. It was designed by Vedat Dalokay, a social democrat who was later to become mayor of Ankara. But by the time construction work finally got under way in the mid-1970s, Dalokay’s almost futuristic plans had long been rejected in favour of the rival Ottoman domes and archways of Hüsrev Tayla and Fatih Uluengin.

Dalokay’s unwanted vision, inspired by a desert tent, was son to resurface as the design for the main mosque in Islamabad. built with the aid of Saudi finance and known as the Shah Faisal. The Pakistani mosque is often described as the largest in the world, its capacity variously put at 74,000-100,000, including the extensive courtyard. Some eight metres lower than Kocatepe, the eight-faceted Shah Faisal occupies a larger, flatter site. Just like Kocatepe, it has four minarets, each 88 metres in height.

To Dalokay admirers, Islamabad’s gain was Ankara’s loss; one modern capital lost out to an even more modern one. Innovative mosque designs are still hard to come by in the Turkish capital, although the low-level mosque of Parliament might be cited, and a Dalokay-style house of prayer has been built at Gölbaşı to the south. Although designed within the constraints of tradition, a number of the neighbourhood mosques which spread across the city in the second half of the 20th century have a character of their own.