Project Description

20. Sayı

Expression

DİPLOMAT – HAZİRAN 2006

20. Sayı

Diplomat

Haziran 2006

Summer heat has come early to Ankara this year, but there has been no let-up in the pace of diplomatic life. The Turkish capital witnesses a royal visit in May, as the King and Queen of Sweden were received by President and Mrs. Ahmet Necdet SEZER. Turkey also received very important guests from many friendly countries including Bahrain, Finland, Colombia, Kuwait, Israel and Russia. While high-level Turkish officials continued their contacts abroad, Ankara also welcomed the arrival of three new and valuable ambassadors.

Once an architect. Ambassador Yves BRODEUR of Canada went on to become an experienced diplomat. He explains how on our ‘Interview1 pages this month. He also outlines the principles behind Canada’s multi lateral ist foreign policy, sets out the Canadian point of view on nuclear energy and the attitude of Iran, and comments on the nature of Canadian society. Of course, the interview also turns to relations between Canada and Turkey, and the impact of the Armenian issue on these relations.

DIPLOMAT’S other guest this month is Ambassador Panidjunai KHALI UN of Mongolia. Mongolia this year commemorates the 800th anniversary of the unified Mongol state. Ambassador KHALI UN offers precious information about the history of his country and its illustrious founder Chinggis Khaan. Besides its warlike past, the anniversary also provides a fine opportunity to become acquainted with the peaceful Mongolia of today.

Our arts pages feature ceramic painter Sitki Olgar, better known as “Sitki Usta”. Olcar is from Kutahya, the capital of Turkish ceramic art since the time of the Ottomans. His work to preserve and develop the genre has made him a world celebrity. His most recent exhibition is currently open in Istanbul.

DIPLOMAT’S travel pages take you to the London district of Greenwich, where, in a sense, time begins. As the reader will soon realise, there is more to Greenwich than the meridian. For those suffering under the Ankara sun, the fresh air of the Thames may make an appealing alternative. But for those who would like to make the most of the sunshine while it lasts, we recommend visits to Gordion, West of Ankara, and to Tokat, a little further to the East, the former best known for its antique legends, the latter for its more recent, Ottoman history.

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current opinion :

The Islamic Conference: Reform and representation

The Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) is currently gearing up for the 33rd session of the Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers, which is to be held in the Azerbaijani capital, Baku, on June 19-21, on the theme of “Rights, Freedoms and Harmony”.

The OIC is composed of three main bodies: the Summit of Heads of State and Government (normally held every three years), the annual Conference of Foreign Ministers and the General Secretariat.

Top issues for this month’s meeting include the Palestinian issue, Islamic financial and economic funds, Iraq, the Iranian nuclear program and conditions in Afghanistan, Sudan, Kashmir and others. Decisions are also likely to be taken on combating Islamophobia, initiating dialogue with the European Union (EU) and the implementation of long-term plans for improving relations among member countries.

The 57 members of the OIC famously make up the largest international organisation after the UN, to which the Conference has a permanent delegation, has more member states. The Organisation also has nine observer states, including Russia and the Turkish Cypriot State. In spite – or perhaps because – of this numerical strength, the OIC is often regarded as no more than a talking shop – a collection of states, many of them small and new, which are quite different in socio-economic, political and even religious terms, and which in some cases harbour rivalries over regional leadership or territory.

Set up in Rabat in 1969, in reaction to the attack on the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the OIC went on to hold its fırst Conference of Foreign Ministers in Jeddah in 1970. It appointed its Secretary General and chose Jeddah as ıts headquarters. Two years later, the Charter of the Organisation was adopted, the purpose of which is to strengthen solidarity and cooperation among Islamic States in the political, economic, cultural, scientific and social fields.

Since then, the OIC has not only increased the number of its members but but also expanded its fields of interest to include areas like culture and sports. Politics and economics have been the central issues, however. In this context, the OIC can claim limited success if any in terms of supporting the Palestinian people to regain their national rights and return to their homeland.

The Organisation’s many standing committees include the Standing Committee on Economic and Trade Cooperation (COMCEC), chaired by the President of the Republic of Turkey. There are also subsidiary organs, specialised institutions and affiliated institutions. For all these organisational efforts, the OIC has also made only modest progress towards its aim of increasing its cooperation among member countries, whether in a bipolar or a monopolar world.

All OIC member states also belong to various other organisations – from the African Union to ASEAN; NATO to the Non-Aligned Conference – and some have joined together in narrower but more focused unions such as the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council or the D-8 group.

Agenda for change

To sum up, the OIC has for three decades served as a broad-based platform for promoting solidarity, dialogue and cooperation among member countries, but has fallen short of rallying its members around a common vision, assuming a cohesive stance regarding issues which are of concern to its member states. Arguably, it has failed to pay enough attention to what has been happening outside its domain. All this has narrowed down the room for manoevre of the organisation in the light of rapid regional and international developments.

Nevertheless, the mere agenda of this month’s meeting sufficiently underlines the relevance of the OIC at a time when the Muslim world is faced with grave challenges in political, security, economic and other areas. Most of its members would agree that the OIC can be an important vehicle to assist the member countries in overcoming these menaces.

The need for reform and revival of the OIC have become all the more urgent in view of dramatic changes in the international political spectrum, particularly in the aftermath of September 11 and the continued marginalization of the OIC in influencing and setting the international agenda, spreading the sense of Islamophobia, and associating Islam with terrorism, extremism and violence. In such circumstances, the OIC, like every institution, felt obliged to redefine its role, rhetoric, function and effectiveness in meeting the expectations of its member states as well as the requirements of the international community.

In an attempt to explore ways and means of increasing the Organisation’s effectiveness, member countries set up the Commission of Eminent Persons in 2004 to prepare a strategy and action plan to promote democracy, civil society, political participation and respect for human rights.

As part of these joint efforts, two basic reference documents on reform were unanimously adopted by the member countries in 2005: a “Ten-Year Programme of Action” and the “Recommendations of OIC Commission of Eminent Persons”.

The Turkish role

As far as Turkey’s relations with the Organisation are concerned, the OIC has been one of the important aspects of Turkey’s multi-dimensional foreign policy. Turkey’s interest and involvement in the OIC activities gained fresh momentum with the election of Professor Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu as the Secretary-General at the 31st Conference of Foreıgn Mınısters in Istanbul, in June 2004, in the first ever freely conducted election in OIC history. With this Conference, Turkey also assumed the rotating presidency until July 2005, and actively supported the initiatives of Secretary General Ihsanoğlu for a widely accepted reform package.

Another breakthrough of the Istanbul Conference was the adoption of the Resolution on the Situation in Cyprus which enabled “the Turkish Muslim People of Cyprus” to participate in the OIC under the name of “Turkish Cypriot State” as envisaged by the UN Secretary General’s comprehensive settlement plan. At its 32nd meeting in Sana in June 2005, the Conference of Foreign Ministers implemented the decision of the 31st Conference and urged member states to remove the political, economic and cultural isolation of the Turkish Cypriots with a view to supporting the rightful cause of the Turkish Cypriots who constitute an integral part of the Islamic World.

The betterment of the situation of the Turkish Muslim Minority in Western Thrace, in Greece has also been on the agenda of the OIC for years. The OIC has taken dozens of resolutions to this effect to safeguard the basic rights of the Turkish minority emanating from bilateral and multilateral treaties to which Greece is a party.

New observers?

Naturally, Turkey is not the only OIC member to seek support for its national causes. The dispute between Pakistan and India over Jammu and Kashmir has been perhaps the most prominent case in point. This issue has also been among the factors standing in the way of India’s interest – as a country with one of the world’s largest Muslim populations – in obtaining membership status at the OIC. As in the case of Cyprus, however, the extent to which OIC members have prioritised this issue in fora other than the OIC and in their bilateral relations with other countries is open to question. Certainly, the impact of OIC positions on the situation on the ground is hard to detect. In other words, the OIC has been ignorable.

In addition to India, the Philippines and South Africa are among the countries seeking involvement in the OIC in view of their Muslim populations – in their case as observers. By cooperating with the OIC, the Philippines may be able to win the moral high ground vis-à-vis its own “Muslim rebels” on Mindanao. That remains to be seen – the OIC is still working on ground rules for such participation.

The OIC is, however, about to take a decision to permit non-government organisations to participate in its deliberations as observers. A growing number of NGOs are understood to have sought observer status.

This development can be seen as a small step towards a return to the OIC’s roots. In the 1920s and 1930s, most Islamic states were concentrating on state building, and others had not yet become independent. All the multilateral Muslim cooperation projects of that era were conducted on a non-governmental basis, as in the case of the General Islamic Conference held in Al-Quds in 1931 and the Islamic Congress held in Geneva in 1935, at which representatives of various Islamic communities living in Europe were present. Only after World War II did inter-Islamic cooperation start to become an issue for states.

Draft OIC rules concerning NGOs would, however, require the groups to be recognised in their home countries and to get permission from their respective governments to join. NGOs submitting requests to join the OIC as observers would be required to have in their founding documents the same goals expressed by the OIC. NGOs would also have to be committed to activities and services benefiting the Muslim Ummah.

Moving centre-stage

As for the proposed reforms of the OIC associated with Professor Ihsanoglu, these may include a new charter which moves on from “apartheid” and “colonialism” to “human rights” and “democracy”. Even the name of the OIC is potentially open to debate (The word “Islamic” will, of course, remain). Transparency, greater involvement as a partner in the international arena, including dialogue with other international and regional organisations, a role in conflict resolution, cultural dialogue with the West and with the rest of the world, fighting disease and coordinating disaster relief – all could be on the agenda.

All this could well involve a trade-off, with the OIC acquiring wider influence and greater external recognition, but in return for adopting aims very similar to those of every other organisation. However, the special relevance of the OIC today surely strems from its potential to act as a voice for Muslims everywhere concerned about injustices, prejudices, misconceptions and “clash of civilisations” ideology. Accordingly, as it seeks more influence by moving closer to the centre of the world stage, the OIC will have to be careful not to become even more marginal to the issues in the minds of 1.4m ordinary Muslims.

—————————————————————————————————–

The OIC System :

- The Islamic Summit

- The Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers

- The Permanent Secretariat (Jeddah)

- Standing Committees

–Al-Quds Committee.

–Standing Committee on Information and Cultural Affairs (COMIAC).

–Standing Committee on Economic and Trade Cooperation (COMCEC).

–Standing Committee on Scientific and Technological Cooperation (COMSTECH).

–Islamic Committee for Economic, Cultural and Social Affairs.

–Permanent Finance Committee.

–Financial Control Organ.

- Subsidiary Organs

–Statistical, Economic, Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (Ankara)

–Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA), (Istanbul)

–Islamic University of Technology (Dhaka)

–Islamic Centre for the Development of Trade (Casablanca)

–Islamic Fiqh Adacemy (Jeddah)

–Executive Bureau of the Islamic Solidarity Fund (Jeddah)

–Islamic Unversity of Niger (Niamey)

–Islamic University of Uganda (Mbale)

- Specialised Institutions

–Islamic Development Bank (IDB) (Jeddah)

–Islamic Edcucational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (ISESCO) (Rabat)

–Islamic States Broadcasting Organisation (ISBO)

–International Islamic News Agency (IINA) (Jeddah)

- Affiliated institutions

–Islamic Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ICCI) (Karachi)

–Organisation of Islamic Capitals and Cities (OICC) (Jeddah)

–Sports Federation of Islamic Solidarity Games (Riyadh)

–Islamic Committee of the International Crescent (Benghazi)

–Islamic Shipowners Association (ISA) (Jeddah)

–World Federation of International Arab-Islamic Schools (Jeddah)

–International Association of Islamic Banks (IAIB) (Jeddah)

Interview :

Ambassador Yves Brodeur: Multicultural, multilateral

by Bernard KENNEDY

In 1985, Canadian diplomat Yves Brodeur left Turkey after completing a tour of duty as second secretary at his country’s embassy in Ankara. Twenty years later, after serving in many other posts and gaining experience in organisations such as the OECD and NATO, he returned as ambassador. As he expected, matters related to trade and investment, regional problems and bilateral ties – including the Armenian issue – were to keep him fully occupied. Ambassador Brodeur, a former architect, has nevertheless found time to reacquaint himself with a much-changed city and its much-changed environs. Our conversation with the ambassador turned to all of this – as well as to the changing nature of Canadian society. But we began by focusing on Canada’s foreign policy…

Q As a member of the Western alliance, how different can Canada’s foreign policy be from that of the US, which is also its closest neighbour and largest trading partner?

A Canada and the US share many common preoccupations, but at the same time we also have a distinctive approach. In 2003, for example, the Canadian policy regarding Iraq was very different from the policy of the US. We do believe in investing and helping Iraq to rebuild its infrastructure as a country and we have invested a lot of money in that. However, the issue for us at the time was whether to take part in the operation in Iraq or not, and the government at the time decided not to.

We are involved in Afghanistan. We are involved in the war against terrorism, which I think is a global preoccupation for all nations of this planet. But we are ardent multilateralists. The UN has been an important forum for Canada to express ourselves and to put forward our values, and we are very attached to it. Canada has just been elected a member of the newly-created Human Rights Council, which was actually an idea promoted by Canada.

Democracy or democratization – whichever term you prefer to use –is very important for us. We prefer the word “governance”, I guess, which is helping nations to build the structures that they need to have functioning democracies.

Q What about Iran?

A We believe that Iran has to conform to the demands of the IAEA. They are important to the UN requirements. We are quite clear on that. Iran has to respond to the UN and we have made that clear to the Iranian authorities. So from that point of view I think we are in the same group as many other countries – not only the United States but the vast majority of world nations.

Q Is Canada a nuclear power?

A No. Canada possesses no nuclear weapons and none can be stationed on Canadian territory. We have decided that we don’t want to contribute to the general proliferation of nuclear weapons. That decision was taken back in the early 1970s at a time when Canada was sandwiched between two nuclear superpowers, the Soviet Union and the US.

Q Will the recent change of government result in changes in Canada’s foreign policy?

A Naturally, it’s the prerogative of the prime minister and the government to reconsider the existing policies. Having said that, I think Canada is a country where there is a quite fundamental consensus. Policy reviews are conducted in consultation with many actors, including various political parties. The emphasis may vary from government to government but the fundamentals are likely to remain the same.

Q So what are those fundamentals?

A The latest foreign policy review led to the publication last year of a new Foreign Policy Statement. The priorities included democracy or governance, promotion, development and security – meaning the security of Canadians and security abroad as well. Those pillars of foreign policy remain pretty constant over time.

Q Does the emphasis on democracy and governance stem from altruism on the part of the Canadian people or is it related to Canada’s interests?

A We have to define the word “interests”. I think there is a vision in Canada – especially perhaps now – that helping existing nations to develop and build solid democratic institutions, will bring more security and more prosperity, and will consequently reduce the global threat. Perhaps there’s a bit of altruism because Canada is a country of immigrants intensely linked to the rest of the planet through its various communities, keenly aware of the situation in many parts of the globe and where people feel that they need to help. But at the same time it is a preoccupation that arises from the need to build a better world which in the end will benefit Canadians as much as developing countries.

Q You have already mentioned the UN. What is Canada’s stance on the make-up of the Security Council?

A We believe that the Security Council has to make room for the opinions of nations which are more and more important players in world affairs. That does not necessarily mean creating more permanent seats. The mechanics of it has to be looked at. We welcome, for instance, the fact that Turkey has expressed interest in being elected for one of the non-permanent seats. This is a very good example of a nation whose regional importance is growing, and which has a lot of clout and experience in regional issues, especially in this part of the world. It should have an opportunity to play a role in such an important institution as the UN Security Council and we support that.

Q How much do Canadians know about Turkey? And what is Turkey’s importance to Canada?

A I would say the level of knowledge among Canadians about Turkey is not what it could be. For the average Canadian, Turkey is a quite far away. Canadians in general are not very knowledgeable about Turkey’s history, and it’s a region of the world where they don’t travel a lot. As for the importance of Turkey to Canada, we value Turkey as a very important ally. We have had official relations since 1947. We work with Turkey in various multinational frameworks and we cooperate on many issues. For a country like Canada which is not very close to this region, Turkey is an entry point and a very valuable contact point. I think this country is quickly becoming, as we say in French, ‘incontournable’ for all of us that want to get a better sense of what’s going on in this part of the world.

Canada takes global security issues quite seriously. Turkey has always been and still is a front-line state – it was in the time of the Soviet Union and it is now because of what is happening in Iraq, the Middle East situation, and the situation with Iran. How could you not value highly your political cooperation with a country like Turkey? Canada has a lot to learn from Turkey on the political front. We have also invested an effort in the countries of the Caucasus – and Central Asia as well – and cooperating with countries like Turkey makes enormous sense.

Q What about the economic and business aspect?

A We see a lot of potential for the development of even closer cooperation and more trade. I think two-way trade will be a little over US$1bn this year. We import more from Turkey than Turkey imports from Canada. However, there is much more potential both for Canadian companies in Turkey and for Turkish companies in Canada. We are also the 14th largest investor in Turkey, but again the amount is not huge. It can only get better, and I am certainly going to do everything I can to bring about an improvement

In general the Canadian companies doing business in Turkey have been doing business here for decades. They have been involved in big infrastructure projects, in subways, in telecommunications networks, in mining… For us I think the challenge now is to encourage fresh investors. Already, Canadian investors are starting to see Turkey as a very attractive market. For example, CanWest, which is a huge communications company in Canada, has become quite interested in Turkey. I think the EU dynamic is helping because it is creating a business environment comparable to that in Europe. The Turkish economy is also becoming more transparent and predictable.

Q Does the Embassy handle a lot of immigration applications?

A No, we don’t have many immigrants from Turkey. A lot of Turkish investors are interested in establishing their business in Canada but not necessarily in terms of becoming resident. What I am working on is to try to attract more Turkish students to Canada. Canada can certainly offer a very competitive environment for higher education. Last year, we had a 35% increase in the number of student visa applications, although we started from very low levels.

Q Have you been aware of the Armenian issue acting as a drag on Turkish-Canadian relations?

A Yes I have. It’s been a sensitive issue between Canada and Turkey since the Parliament of Canada adopted a motion in 2004. Unfortunately, it’s not something that we can just ignore. I know it’s a very important issue for Turkey and I understand Turkey’s sensitivities. I think we have a solid bilateral relationship and I think that will help us during the difficult discussions which we are going through now. I am reasonably confident that we will be able to find a way out and renew cooperation to the benefit of both sides.

Q What are the concrete effects on relations?

A Well it is difficult to measure. Business people continue to do business together. We still maintain close relations on defence and security and that sort of thing. But I think it’s fair to say that we are going through a period of slow-down. It’s obvious when you speak to Turkish colleagues: they make you clearly understand that this is an unfortunate development for them and that they are disappointed. They are not necessarily as eager as they were about working together. The most concrete signal was the recall of Turkey’s ambassador to Ottawa, Aydemir Erman, for consultations.

Q Did Prime Minister Stephen Harper say anything on April 24 that was different from what has been said before?

A The Prime Minister basically reminded Canadians of the terms of the motion adopted in 2004. He was clear about that, saying: Our position as a party has not changed.

Q What would you like people to think of when they think of Canada?

A Canada is very much a multicultural society. I think this is quite important because in some countries ethnically based nationalism is making a big come-back. We are admitting some 350,000 immigrants to Canada each year. We still have an active immigration policy and that gives Canada a very distinctive character. I think Canadians are defined by values rather than by a notion of identity based on, say, ethnic origins or language. People ask about the language divide between English and French, but Chinese is spoken widely too. This experience can perhaps help nations to understand better how multicultural nations work and function. I am not saying we have found a magic solution or that we fully understand multiculturalism but we have been practising it for long enough to know that there are some good elements that can be looked at and perhaps adapted in other parts of the world.

Q There’s a view that multiculturalism actually stands in the way of integration…

A Somehow we seem to have struck the right balance. Multiculturalism seems to allow people to maintain their culture at the same time as adopting Canadian values. I think this has something to do with how the Canadian identity is defined. It’s not the flag, not a language, not the territory… Perhaps it’s more about tolerance and open-ness. And really we don’t have a choice about those values in a society where we have so many people from so many different backgrounds; otherwise it simply wouldn’t work.

I think another aspect of Canada worth studying is that we seem to have been able to combine a European-style social tradition, in which the state has a lot of responsibility when it comes to health and education, with a vibrant, decentralized, open liberal economy. When I was at the OECD fifteen years ago, a lot of people thought the two concepts didn’t go together, but we seem to have come up with a hybrid system that brings prosperity while ensuring that Canadians have protection and access to good social services and education, among other things.

Q Coming back to Turkey, I believe this is the second time you have lived in Ankara…

A Actually it’s the third time. My first diplomatic assignment was in 1983-1985. But I first came in 1977 as a part of a student exchange programme. I shared my time between Mimar Sinan University in Istanbul and METU in Ankara. My main interest was in Ottoman architecture. One of the projects I worked on was the restoration of some of the old houses in Safranbolu… Last week I went back to Safranbolu for the first time in 23 years. Wow! What a spectacular change!

Q What other changes have you noticed?

A In the 1980s, Ankara had an almost rural quality to it. There was a vineyard where the Sheraton Hotel is now, and the big mosque at Kocatepe didn’t exist: it was still a market area where we had to go to do our weekend shopping. The size of the population and quality of the city is quite different now. The city is livelier, busier and greener, with a lot more parks and trees, but it’s also a noisier city with lots of cars. At times it’s a little chaotic. It reminds me a bit of a government-university city like Ottawa, or Bonn. We are happy to be here.

Q How has diplomatic life changed?

A Now we have 55 people working at our embassy. In those days we had only 15. We had no immigration section. We had a visa section but it was mostly to process visitors’ visas; we had very few students coming to Canada. Our trade operation was very, very small.

Life in 2006 is extremely busy. I don’t think a day passes without a very high level delegation coming to town led by a head of state or government or a minister. Many of the diplomats here are people who have had very senior posts in their foreign ministries. I think this is a sign of Turkey’s importance. At the same time, Ankara is a place where interaction is rather easy. It’s easy to get access to your colleagues, to Foreign Ministry officials and to other departments. I think people are eager to develop a good relationship. They do everything they can to make your life easier.

Q Was it your choice to come back to Ankara?

A I think some diplomats come here under the impression that they will have a quiet time. I volunteered to come here knowing the country to some extent and with the intention of working very hard. I also came back to meet up with friends whom we met 25 years ago and have maintained close contact with. It’s a privilege to be able to follow the evolution of a country like Turkey over a period of 30 years, and it’s always fascinating to go back to places you have visited before. My wife and I have extremely good memories of life in Turkey. This summer our children will be coming to see us. My son, who was with us in the 1980s, is extremely curious to see again the city where he lived when he was very very young.

Q Do you ever regret becoming a diplomat instead of remaining an architect?

A Life is an evolutionary process – not a series of separate segments. In the new world we live in, you often run into people with two or three occupations. I find that stimulating. I think life would be boring if you didn’t have to learn something different all the time. It keeps you healthy; it keeps you young. One of the good things about being a diplomat is that your life changes every three or four years: you’re told to do something quite different, involving different issues, with different people, in a different environment and a different culture. So you find yourself in a situation where you have to sit down and learn again. Architecture was great. As a problem-solving methodology, what you learn as an architect is applicable afterwards to other walks of life. But I have no regrets about changing my profession. At the same time, I maintain an interest in architecture – in Turkey as well. Architecture tells you a lot about the people, the culture of where you are. Moreover, my son is an architect in Canada so I keep in touch with the profession in that way too. Maybe he will become a diplomat or something else one day! Life is full of surprises.

Human angle :

How to approach the population problem

by Prof. Dr. Özer OZANKAYA

In the history of the development of scientific thought, calls for the avoidance of rigid thinking have been made systematıcally sınce the 17th century. The famous English philosopher, Francis Bacon’s encapsulates the thinking of this time by saying, “If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts.”

This thinking is also very relevant, and can be applied as an approach, to the rapid population growth which is becoming a growing concern and problem for humanity today.

Western countries were the first in the history of humanity to enter the process of industrialisation and hence to experience the rapid population growth of our times. The English priest Malthus made a prediction about this issue. He believed that because land is limited and human capability to reproduce is unlimited, food production can increase only with arithmetical speed, while population will increase at geometric speed. Unless measures such as never marrying, or marrying late, and avoiding sex outside marriage, are taken, it is inevitable that this imbalance will end with deaths on a mass scale due to epidemic diseases, wars and scarcity.

Although these countries were the first ones to experience the destructive years of capitalism, where pregnant women worked for 16 hours a day and 6 year old children were expected to work for 14 hours a day, Malthus’ theory was falsified by the conditions of the industrial environment and put aside. In the conditions of industrialised cities, the masses realised that the social environment was not unchangeable, but that it could be understood with reason, and its unwanted elements could be adjusted, so that conditions could improve after much democratic struggle. Thus it was understood that births and deaths were not only “biological” facts; rather they were “cultural” events shaped by social-economic conditions. It was seen that the conditions of the industrial environment had a limiting effect on the large number of births and deaths, especially infant deaths. Furthermore, scientific-technological developments achieved during the industrial environment largely increased agricultural (food) production.

In brief, industrialised cities in Western countries managed, albeit after many struggles and with the aid of resources transferred from other countries, to reduce the infant death rate and increase life expectancy by – among other things – raising living standards, improving nutrition and health awareness, preventing epidemics and creating a healthy environment. Meanwhile, the level of education rose, including education of women, and women took more jobs and entered the professions. They increased their economic output and their living standards. Conditions became more egalitarian, liberating and individualist, the areas of human interest and expertise became stronger and more diversified. All this reduced the number of births.

In this way the population of Western countries reached a slow growth rate (in some of the industrialised countries there was zero-growth). This is the “modern balance”, where both birth and death rates are at very low levels.

The non-Western world

The second highest population growth spurt in history occurred in non-western countries, namely Asia, Africa and Latin America, after the Second World War. The Malthusian approach had been abandoned in the 19th century – or so it was thought – but in the face of this new “population boom” it has been re-adopted and still continues today.

Neo-Malthusianism thinking has sought to find solutions to the problem of the “Population Boom” through providing contraception and various birth control techniques, voluntary sterilisation, planned parental courses and the distribution of handbooks and guides. This approach is known as social-Darwinist – in other words a racist approach – and ignores the fact that human reason is shaped according to the social-economic-cultural environment – not only in the West, but everywhere.

Thus, the function given to Malthus’ theory is to explain the economic backwardness and poverty prevailing in four fifths of the world with rapid population growth, and to make it possible to overlook the question of responsibility for the international exploitation which prevents these countries from reaching the industrial-urban societies. Advanced societies were able to overcome the population problem essentially as a result of the industrialisation process. But today the world refuses to accept is that underdeveloped societies are experiencing a population problem because they have been prevented from becoming industrialised.

This approach ignores the difference between correlation and causality. In other words, the appearance of two facts together does not necessarily mean that there is causality between them; it is possible that both can be attributed to another common cause. With respect to our subject, considering the rapid population growth as the main cause of underdevelopment (because population growth is rapid in underdeveloped countries) means that this difference is overlooked. Another unfair assumption would be to believe that rapid population growth is caused by the large family structure or vice versa. Just because the large family structure is widespread in rural areas where the population increases rapidly does not mean that one leads to the other.

An artifical example

Furthermore, let’s suppose for a moment that we could curb the population increase in a given country by limiting the birth rate purely through the use of artificial means (pills, education etc.) – the much-prized method followed today. The effect on the population would not lead, for example, to agriculture in that country becoming equally or more productive with a lower level of manpower. However, if we take measures that would relieve agriculture from being dependent on manpower, in other words mechanise it, we can see that the population growth would actually decrease. So, it is also necessary to make the distinction between dependent and independent variables: whereas births and deaths are dependent variables, the implementation used for production necessary for living is an independent variable.

The fertility structure of Western countries before industrialisation took place was very similar to the situation we see today in underdeveloped countries. Two German sayings sum up the situation: “Der Wunsch nach einem Sohn, ist der Vater vieler Töchter” (The desire for a son, is the father of many daughters!), and “Die Reichen haben die Rinder, die Armen die Kinder” (The rich have cattle, the poor have children).

Worlds apart

The industrial-urban environment and democratic political culture in the West have been the main independent variables that eliminated both poverty and high fertility rates. In particular, the need for women to work as a result of the increase and diversification in needs led to a strong sense of the necessity to limit births. The increasing concentration of the population in cities, where the average age of marriage is higher than in rural areas, has also decreased birth rates. Income has improved as well as the level of education, health and security. Conditions for raising children and their survival have greatly improved and limiting the birth rate does not bring with it the danger of remaining childless. A wide variety of fields of human interest and activity has opened up besides the raising of families.

In underdeveloped countries the industrial and urban environment cannot emerge, For the majority of the population, the division of labour and patterns of solidarity are mechanical rather than organic, and because life activities are not diversified, sexuality remains too important among human activities. For the same reason, women are deprived of basic human rights and freedom and the results are the same. The level and quality of education is extremely low and nutritional knowledge is weak, so the masses cannot be certain that their children will survive, since the infant death rate is so high. They cannot think about birth control under these circumstances and consequently continue to give birth to many children.

In these countries, security services in the narrow sense are not provided and having a large family, especially many sons, is preferred for security reasons, and as a result the self-esteem of these families increases.

The wrong strategy

As can be understood from these explanations, the strategy that should be followed to fix and balance the population boom in non-Western countries is to encourage these countries to reach industrial-urban conditions and to establish more democratic government which tries to eliminate various internal and external obstacles by learning from more experienced Western countries which have passed through similar circumstances in the course of history.

Unfortunately, we are witnessing the exact opposite of this. In our post-modern period, capitalism is presented as being the goal of Jesus, and in order to maintain it, the industrial and financial institutions of the countries mentioned are being undermined, their natural resources are being exploited, their markets are being seized and their citizens are being used as cheap labour.

The new Malthusianism is not merely content to emphasise “family planning” – complete with education, contraception and voluntary sterilisation. This was the Cold War era approach. Since the collapse of socialism, a new and incriminating argument has emerged to the effect that the peoples of non-Western countries are unthinkingly “giving birth to children as if eating olives and throwing away the stones”. This opens the door to a Population Reduction Strategy including the creation of economic crises, famines and hunger, and the triggering of regional and civil wars based on ethnic, religious and sectarian divides, as a possible solution to the population boom. American sociologist Susan George describes this social-Darwinist strategy with many supporting documents in her study The Lugano Report (Pluto Press, London, 1999).

A better path

The strategy most appropriate for civilised humanity is to prepare for the future by learning from the past, to realise that it is possible to establish a social order within which all humanity can live happily in peace and prosperity, and to implement an international policy based on the understanding that every nation has the right to a level of development commensurate with contemporary science, art and technology – and that it is necessary to support, not hinder, nations in their efforts.

Wise people can easily see that this well-intentioned plan, if followed by entire humanity, would be the most beneficial for their own personal and national prosperity.

Today, approximately 40 percent of the population of underdeveloped countries is between the ages of 0-14, and another 50 percent are under the age of 40. In other words, for many years the rate of the biologically productive section of the population in these countries will be high. Yet at the same time these people are at the age when they can be most productive in the economic and cultural spheres. The sooner we start to remove the internal and external obstacles which they face in achieving conditions of industrial-urban-democracy, the surer we can be of the peace and happiness of the whole of humanity in future.

Regrettably, the economic conditions dominating the world at present have yet to acquire a moral dimension. The neo-Malthusianism is one of the indicators of this anomy.

World View:

The Admirable Ireland

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya Ataöv

There are two Irelands. The first is called “Northern Ireland”, which is one of the four units constituting the United Kingdom of Great Britain. The other three are the lands of the English, Scots, and the Welsh. The “admirable Ireland” that I am referring to is the Irish Republic in the south of the smaller island. The latter comprises 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland.

The U.K. was established in 1707 when the parliaments of Scotland and England joined together. “Ireland” was added to the official title in 1801 with the dissolution of the Irish parliament. The original Scots, who gave their name to Scotland, were also Gaelic-speakers from Ireland. Anglo-Saxons called the speakers of Welsh, a Celtic language related to Cornish and Breton, “Wealas” (foreigners), from which derives the word “Welsh”. By the beginning of the 17th century, England conquered and controlled the whole of Ireland. Full-scale rebellion broke out three decades later. In 1905 Sinn Fein was founded, aiming to re-establish independence. The Protestant majority of the Six Counties in the North remained part of Great Britain, however rioting damage and deaths continued in Northern Ireland, representing only the tip of the iceberg of political, religious and social conflicts which have a history going back centuries ago. In 1922 civil war broke out, and in 1949 the Irish Free State became the Irish Republic The 1937 Irish constitution had also claimed Northern Ireland as well.

Attempts to understand the fraught situation were made more difficult because of the interaction between the English, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The long tradition of Gaelic Ireland was overlaid by Anglo-Saxon settlers. With English colonization the Protestants gradually became the majority in the North. Separated by natural terrain, Ulster in the upper region had a distinct character from the rest, that difference becoming more marked with the development of the North during the Industrial Revolution. Trade policies stressed the economy of Southern Ireland and encouraged the growth of Belfast, which had close links to Glasgow and Liverpool. Protestants and Catholics flocked to the bigger cities, but each to their own areas. The Republic of Ireland in the south also had a very small (3.3 %) Protestant minority. The solution may lie in talks around the table and in the new circumstances of the European Union, where the economic interests of all the Irish will be the same.

I first set foot on Irish soil in February 1955 when an old four-engine plane destined to take me to New York for graduate studies had to stop and give a break at the Shannon airport on the most westerly edge of the European continent, for a final gas refueling before heading across the Atlantic. From the courses on world literature at Robert College (RC, Istanbul) I knew that some of my favourite writers like Swift, Sheridan, Shaw, Synge, Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce were Irish, but that stop exactly half a century ago happened to be in the middle of the night, and all I saw were only a few Irish faces. My studies in the U.S. took about four years, at the end of which I joined the teaching staff of the International Relations Section of Ankara University. It was in 1991, on the invitation of our ambassador and his first secretary, both my former students, that I went to Dublin after attending a seminar in West Sussex (U.K.).

Our ambassador then, Halil Dağ, now retired, was a self-made man with a modest family background but who proved to be an intelligent and a hard-working individual with principles and discipline. He married a young British lady during an earlier appointment abroad. His counsellor, Deniz Özmen, now Turkey’s ambassador in Seoul, was also an outstanding student in school and married the daughter of my illustrious commander while I was performing my military service as a reserve officer. Their son was then one of the few Turkish children who knew some Irish (or Gaelic). Through their courtesy, I had a much longer glimpse of Ireland and I found its people to be admirable.

I not only spent some time in the capital city but also had a chance to see some other places, including some of the inspiring seashore. I took notes and photos, and also made drawings. Like all visitors, I adored the accomplishments of the old Trinity College of Dublin. There I learned that playwrights Beckett, Behan, O’Casey and Lady Gregory, poets Mangan, Kavanagh and MacNeice, novelists O’Brien, O’Flaherty and Edgewotrh, and other writers such as Burke, Lecky, and Lynd were all Irish. I had listened to poet Louis MacNeice’s lecture at RC’s conference hall and heard his recitation of his own verse that started with the line “I am not yet born/O, hear me!”. I had then tried to render that lyrical piece into Turkish, which some of my class-mates thought was “not bad”.

Four decades after that I read the lines of Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill, who is perhaps the greatest contemporary poet writing in Irish. Having once been at the farthest western corner of Ireland, I am now pleasantly surprised to read the following description: “…with honeyed breezes blowing over the Shannon”, from one of her selected poems translated by M. Hartnett. The Irish Literary Supplement writes: “Her voice thunders, and you can only marvel at the consistency and quality of that unified voice.” I had then watched Dhomhnaill on television. She is expressive, forceful, convincing and poetic, all the way through. Did you know that she is married to a Turk and has four children? She describes Turkey as a “wonderful country.” It was also another pleasant surprise to learn that James Clarence Mangan (d. 1849), a Dublin poet, was the first to translate Turkish poetry (via German) into English.

Much of the Irish poetry, on the other hand, is linked with the country’s history, or its continuous struggles against invasion for liberty. A line from an anonymous poem in early English says: “…holy londe of irlonde…” It is a holy land for the Irish, who pride themselves as patriots, as John Hewitt put it, “since Clontarf’s sunset saw the Norsemen broken…They entered their soft beds of soil/not as graves, for this was the land/that they had fought for, loved and killed/each other for.” Ireland earlier saw the Viking terror, and much later the faces of the young English soldiers, who look, in the words of Padraic Fiacc, like “lonely little winter robins.” Catholic Ireland still remembers the revolt of the 1640s, suppressed by Cromwell. There exists much writing on the events of those years and the second Irish civil war. Especially the Catholic siege of Londonberry and the Battle of Boyne stand out as the two episodes still celebrated every year. In the wake of another rebellion the Protestant Irish Parliament in Dublin was suppressed. But Irish Catholic men finally won the vote in 1829, just before the potato famine of the 1840s. the greatest disaster of Irish history.

The famine cost many lives and led to mass emigration to North America, England and Australia. About the Irish in the U.S., Walt Whitman wrote: “What you wept for was translated/The winds favor’d and sea sail’d it/and now with rosy and new blood/moves to-day in a new country.” The İrish population was 8 million before the famine, and never managed to recover. The emigrants’ descendants kept their religion and Irishness. The former U.S. President John F. Kennedy, for instance, was a fourth-generation American, his great grand-parents having emigrated on account of the same famine. Those who went abroad still remembered the “abandoned roads reaching across the mountain, threading into clefts and valleys, shuffling between thick hedges of flowery thorn.” The old country was a place of nostalgia. Ireland continued to give new names for the country. W.H. Auden wrote for Yeats: “Earth, receive an honoured guest; Williams Yeats is laid to rest.”

The Irish are generally described, however, as being incurably optimistic. They take a delight in jokes. They even print selections on linen tea towels. One reads: “There are only two things to worry about. either you are well or you are sick. If you are well, then there is nothing to worry about. But if you are sick, then there are two things to worry about: either you get well, or you will die. If you get well, then there is nothing to worry about. If you die, there are only two things to worry about: either you will go to heaven, or to hell. If you go to heaven, there is nothing to worry about. But if you go to hell, you’ll be so damn busy shaking hands with friends, you won’t have time to worry. So why worry?”

Speaking out:

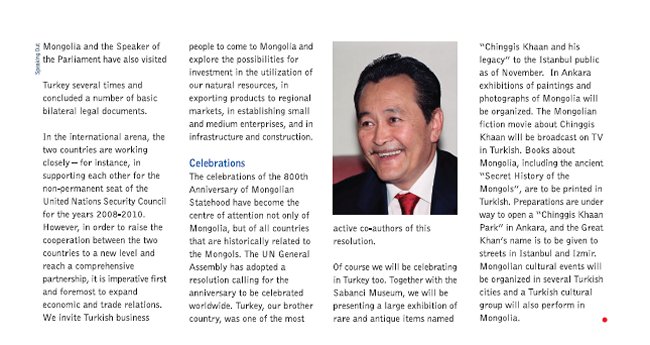

Ambassador Khaliun: Mongolia’s octocentenary

Next month, Mongolia will be celebrating the 800th anniversary of the unified Mongolian state created by Chinggis Khaan in 1206. Here, Mongolia’s Ambassador to Ankara, Panidjunai Khaliun, explains the background to this occasion and describes the planned festivities. We also asked him to comment on Mongolia’s relations with Turkey and with its larger neighbours.

This year, we Mongolians are fortunate and proud to have the chance to celebrate an auspicious event in history: the 800th anniversary of the unified Mongolian State. A National Committee headed by the Prime Minister is organizing activities throughout the year. All ministries, non-governmental organizations and economic entities are actively involved. The climax will come during the National Day celebrations (“Naadam”) on 11-13 July, which will be attended by high dignitaries from other countries. The three manly games – namely the national wrestling competition, horse-racing and archery – will be staged, and there will be a major cultural festival with international performances. In Ulaanbaatar city, a Chinggis Khaan ceremonial palace will be erected, and a museum will be built in the Great Khan’s birthplace. New documentaries and a feature film about Chinggis Khaan, his descendants and Mongol warriors will be broadcast to the public.

Historical roots

Mongolia’s history as a state goes back to the end of the Third Century B.C., when the Hunnu State was first formed. But in 53 A.D. the Hunnu State disintegrated into the South and North. The Northern Hunnu State became strong during the reign of Attila Khan in around 445 A.D. Although the Southern Hunnu State was subordinated by the Chinese, its people regained their independence following an uprising in the First Century, and retained it until the Tenth Century.

Until the end of the Twelfth Century, the Mongols as a nation were weak, fragmented into small fieldoms that continuously fought each other. Historical records show that at the age of 15, Chinggis Khaan was already resolved to put things in order. Many well-known scholars around the world have attested to his superior organizational skills and effective military tactics. In almost every battle, he would come out victorious, although outnumbered 5-10 times.

The Mongol warriors of that era were men of strict discipline and extreme loyalty. They were organised into groups of ten warriors. Each ten was divided into threes, who were headed by one senior officer. Mongolia’s economic and political situation and its military organization resulted in a military state, and Chinggis Khaan struggled to create a World empire with a supreme ruler.

Chinggis Khan the statesman

But the Mongols in history were not merely a warlike people. On the basis of historical documents, historians and researchers have come up with different interpretations of the so-called atrocities perpetrated by Chinggis Khaan and his warriors. He emerges as a charismatic personality who treated his followers justly and paid great attention to cultivating the loyalty of his followers. He promoted his followers largely according to their loyalty and ability, but he was ruthless in suppressing disloyalty.

After defeating his enemies, Chinggis Khaan freed the people from his enemies’ tyrannical rule and set up new governments. Since its establishment 800 years ago, Chinggis Khaan and his successors, Ugudei, Guyug, Munkh and Khubilai Khans, made the Great Mongol State the world’s greatest empire in history.

In his statecraft, Chinggis Khaan constantly emphasised three main ideas – justice, equal rights, and unity. Soon after the Great Mongol State was established in 1206, he declared the Great Yasa, the State law of the nomadic civilization, which has been much admired since. He developed diplomatic relations and created and developed free trade and a postal service. Important decisions on matters of state were taken jointly. In contrast with many other empires, the Mongol empire tolerated all religious beliefs and practices, and many religions coexisted in one state. For these reasons, Chinggis Khaan has been described as “the Man of the Millennium”.

Mongolia also has more recent achievements to cooperate. At the beginning of the 18th Century, the Mongolian people came under Manchurian rule for over 200 years. The Mongolian people’s national liberation movement had its first victory in 1911, and on July 11, 1921 the People’s Revolution triumphed, and a new era of prosperity for Mongolia began. On November 26, 1924 Mongolia declared its independence. Many young Mongolian fighters engraved their names in the pages of modern history during this fight for freedom and independence. Among them were noblemen, government officials, military personnel, and common people alike. To this day, Mongolian people recognize and respect these modern heroes. Throughout all this we have remained a hospitable people. Separated by tens of kilometres from each other, Mongols in the countryside still have a custom of leaving their dwellings open with some food available for any traveller who wants to stop and take a rest.

Mongolia in transition

For more than seven decades, my country developed along the socialist path. During that time we had both accomplishments and mistakes. While Mongolia’s economy had been solely based on animal husbandry, it was able to develop agriculture, light industry, transportation, communications and construction. A great deal was accomplished in the areas of health, culture and education.

At the beginning of the 1990s, a democratic revolution triumphed. The country made a transition to democracy and the market economy. A specific feature of the democratic revolution lies in the fact that it was bloodless. Mongolia was the first to make such a transition among the socialist countries of Asia.

But the process of transition does not come easily. In the blink of an eye we lost all our traditional partners. The new Mongolia was faced with the task of building relations with new countries. Between 1990 and 1994, the income of the population plummeted, unemployment increased and living conditions worsened. However, with the assistance of Japan, the Republic of Korea, the United States, Germany, Turkey and other countries, Mongolia has been overcoming those difficulties. In 2004, the economy grew by 10.6% compared to only 4% in 2002 and 5.5% in 2003. Since 2000, inflation has fallen to 8.1%.

Mongolia’s GDP is comprised as follows: agriculture – 20%; industry – 22%, construction, transport and communications – 17.5%, trade and services – 40%. Mongolia’s livestock population of more than 30 million has been privatized. That is the main self-reproductive wealth resource of the Mongolians. In the bowels of the earth are to be found other immense riches. Significant deposits of gold, copper, zinc, uranium and coal attract foreign investment. Today, the mining sector makes up 17% of the country’s GDP and 64% of industrial output.

Mongolia is highly gratified with the level of its relations with its two neighbours, the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China. For all the ups and downs in the relations with these major powers in the past, Mongolia is looking to the future with optimism. Meetings at the highest levels have become a regular phenomenon. Interaction in the economic, cultural and other spheres is picking up speed. China has become Mongolia’s largest trading partner. The issue of “big” debt with the Russian Federation has been resolved in an amicable manner bearing in mind decades-long relations of friendship and cooperation. Our trade turn-over with Russia is reaching new highs.

Mongolia and Turkey

Centuries of historical ties and similarities in customs, traditions and historical and cultural backgrounds constitute the mainstay of today’s brotherly relations between Mongolia and Turkey. Mongols and Tureg (Turkish) speaking tribes shared a common border for hundreds of years, leaving strong imprints in the history, culture, customs and traditions of the two countries. For instance, the modern Mongolian and Turkish languages share more than 400 words similar in meaning, and over 3,000 words with the same root. Not far from the ancient capital city of Karakorum in the Orkhon valley stand the monuments of Bilge Khan and Chieftain Gultegin – a rare and priceless proof of the historic contacts between our two countries.

Since the 1990s, Mongolian-Turkish relations and cooperation have expanded into many new fields. High-level visits between the two countries have played a decisive role. After the first visit of H.E. Suleyman Demirel, President of Turkey to Mongolia in 1995, Mongolian boys and girls received scholarships to Turkish higher educational establishments. Last year, during his visit to Mongolia, the Turkish Prime Minister R.T. Erdogan increased the students’ quota twofold. Currently around 700 young people from Mongolia are studying in Turkey either privately or under inter-governmental agreements. This means that the future generation is on their way to continue and further develop the brotherly relations between the two countries. The President of Mongolia and the Speaker of the Parliament have also visited Turkey several times and concluded a number of basic bilateral legal documents.

In the international arena, the two countries are working closely – for instance, in supporting each other for the non-permanent seat of the United Nations Security Council for the years 2008-2010. However, in order to raise the cooperation between the two countries to a new level and reach a comprehensive partnership, it is imperative first and foremost to expand economic and trade relations. We invite Turkish business people to come to Mongolia and explore the possibilities for investment in the utilization of our natural resources, in exporting products to regional markets, in establishing small and medium enterprises, and in infrastructure and construction.

Celebrations

The celebrations of the 800th Anniversary of Mongolian Statehood have become the centre of attention not only of Mongolia, but of all countries that are historically related to the Mongols. The UN General Assembly has adopted a resolution calling for the anniversary to be celebrated worldwide. Turkey, our brother country, was one of the most active co-authors of this resolution.

Of course we will be celebrating in Turkey too. Together with the Sabanci Museum, we will be presenting a large exhibition of rare and antique items named “Chinggis Khaan and his legacy” to the Istanbul public as of November. In Ankara exhibitions of paintings and photographs of Mongolia will be organized. The Mongolian fiction movie about Chinggis Khaan will be broadcast on TV in Turkish. Books about Mongolia, including the ancient “Secret History of the Mongols”, are to be printed in Turkish. Preparations are under way to open a “Chinggis Khaan Park” in Ankara, and the Great Khan’s name is to be given to streets in Istanbul and Izmir. Mongolian cultural events will be organized in several Turkish cities and a Turkish cultural group will also perform in Mongolia.

PHILATELY

The Conquest of Istanbul

by Kaya DORSAN

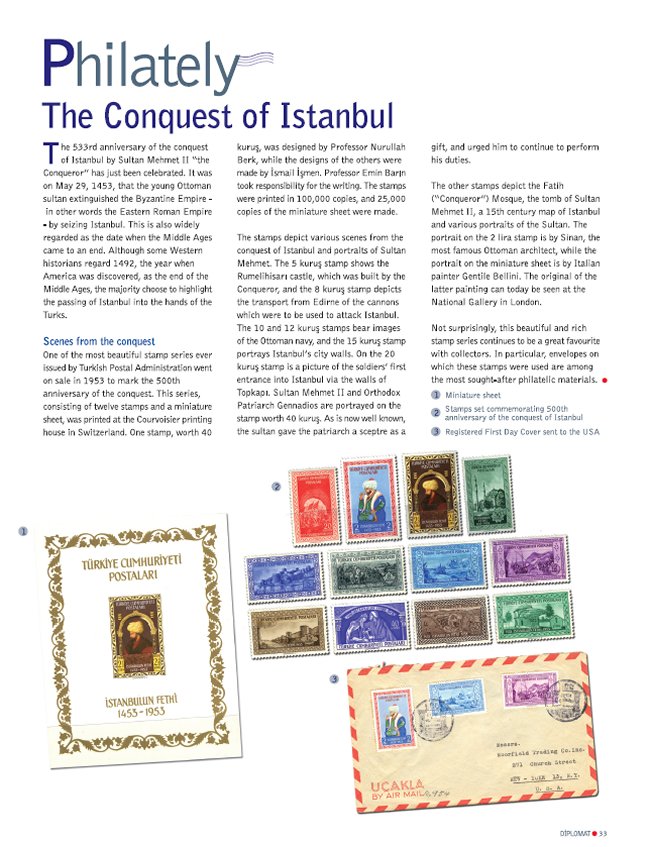

The 553rd anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul by Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror was celebrated recently. Young Ottoman Sultan had eliminated the Byzantine Empire, in other words the Eastern Roman Empire by seizing Istanbul on May the 29th, 1453. This date is also the date when the “Middle Age” ended. Although recently some Western historians accept the date 1492 when America was discovered as the end of the Middle Age, the majority predicates on the passing of Istanbul into the hands of Turks.

Scenes from the conquest

One of the most beautiful stamp series issued by Turkish Postal Administration was put up for sale in 1953 due to the 500th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul. This series, consisting of 12 stamps and a “miniature sheet” was printed at the Courvoisier printing house in Switzerland. Among these stamps, scenes from the conquest of Istanbul and portraits of Sultan Mehmet are depicted. One stamp is worth 40 kuruş and was made by Prof. Nurullah Berk, the design of the others were made by İsmail İşmen. The writing on the stamps were prepared by Prof. Emin Barın. 100,000 copies of the stamps where printed, while 25,000 copies of the miniature stamps were copied.

On the stamp worth 5 kuruş, Rumelihisarı built by the Conqueror and on the one worth 8 kuruş, bringing of the cannons from Edirne which were to be used to attack Istanbul are depicted. On the ones worth 10 and 12 kuruş Ottoman navy, on the one worth 15 kuruş city walls of Istanbul are portrayed. The picture on a stamp worth 20 kuruş describes the soldier’s first entrance into Istanbul from the walls of Topkapı. Sultan Mehmet II and Orthodox Patriarch Gennadios are portrayed on one worth 40 kuruş. As it is known, the Sultan had given a scepter as a gift to Patriarch Gennadios and urged him to continue his duty. On the other stamps, Fatih Mosque, tomb of the Sultan Mehmet II, the 15th century map of Istanbul and the portraits of the Sultan take place. The famous Architect Sinan made the miniature portrait over the stamp worth 2 liras and Italian painter Gentile Bellini made the portrait over the miniature sheet. The original of this painting is still displayed at the National Gallery in London.

This beautiful and rich stamp series continues to be the favourite amongst collectors even today, especially the envelopes used with these stamps as they are considered to be amongst the most sought after philatelic materials.

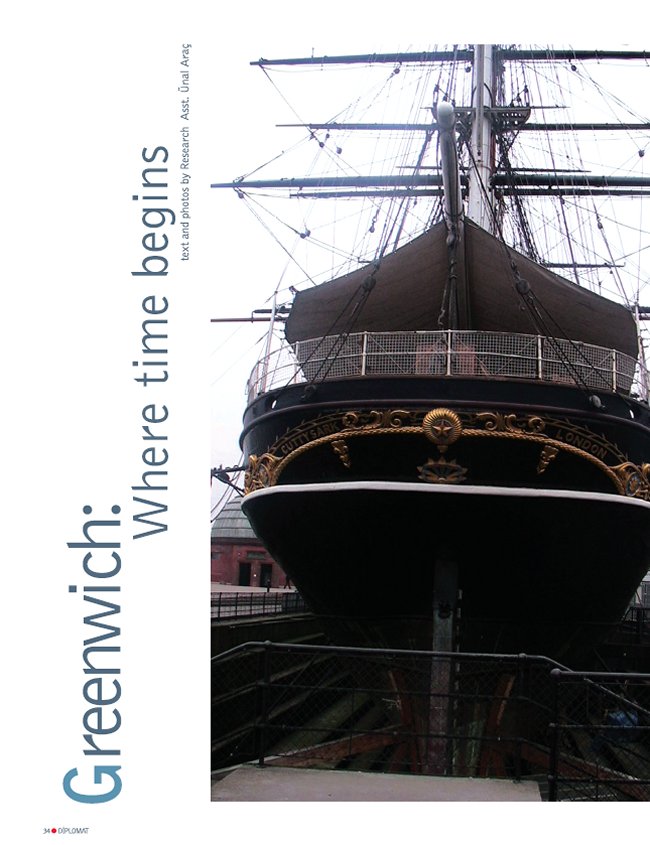

Greenwich: Where time begins

by Research Assistant Ünal ARAÇ

Greenwich covers an area of 46 square kilometres on the south bank of the River Thames within the metropolitan area of London, England. Despite giving its name to the Greenwich meridian, the district has often been overlooked as a place of interest by visitors to the British capital. Today, however, foreigners and Londoners alike are enjoying the buildings and museums and history of the district, as well as its pleasant park – a peaceful environment far removed from the city centre traffic or the business towers of the Docklands across the river.

There can be no better way to understand the role which the River Thames has played in the development of the capital of London than to take a boat trip down it on a sunny day. From Westminster wharf, you pass through the ‘City of Westminster’ and the ‘City of London’, taking in glimpses of Big Ben, the Houses of Parliament, the Royal National Theatre and many other landmarks new and old. Then it’s downstream for a visit to the ‘Tower of London’ – and on to the docks. Your guide will point out the Doric column of the Monument built for the commemoration of the great fire. London Bridge, which symbolises the history of London like no other monument, requires no introduction. Finally, on the left, looms the Isle of Dogs peninsula, with the famous Millennium Dome, and the Canary Wharf Tower. And on the right – also accessible via the underground ‘Jubilee Line’ railway or a train from London Bridge station – is Greenwich.

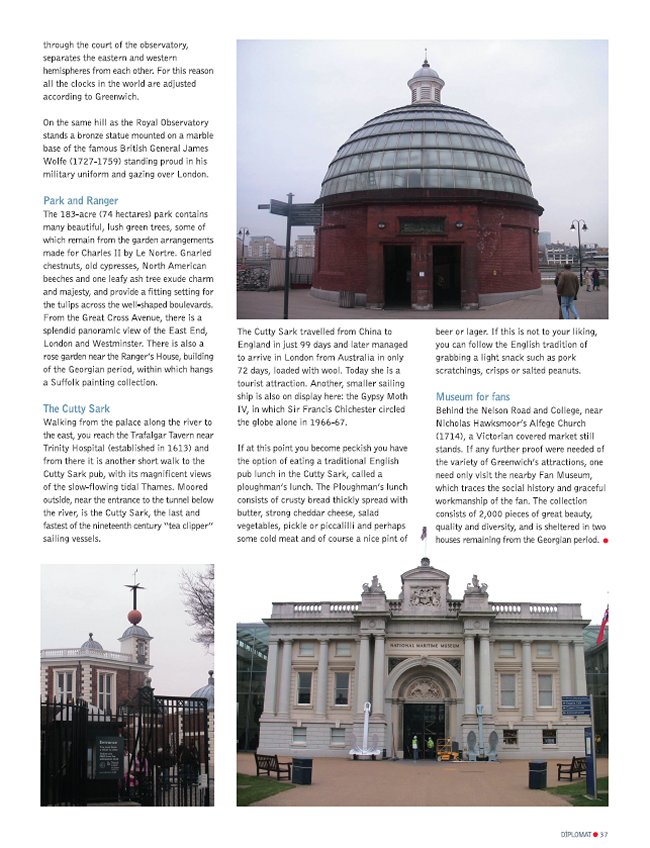

For leisure travellers, Greenwich is a veritable jewellery box. The best known treasures are the royal palace complex, the extensive maritime museum and the Royal Observatory, accepted as the site of the Prime Meridian. But the river bank, the park and the surrounding streets offer many more surprises.

Royal Greenwich

Greenwich was at its liveliest during Tudor times and in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. The park, covering 74 hectares, was first enclosed and laid out six months after Bela Court was built in 1427 by the Duke of Gloucester, who was the brother of Henry V. Henry VII, another king of the Tudor Dynasty, was to choose this area as a suitable spot on which to build the Palace of Placentia in 1500. Henry VIII, who was born in Greenwich Palace, added many more constructions, including a banqueting hall, arsenals and an area for jousting. Greenwich Park also served as a place where the royal family and their entourage could hawk and hunt deer.

Henry VIII’s daughters Mary and Elizabeth I, as well as his son Edward, were born here too. In 1512 and 1513, under Elizabeth I, two royal shipyards were founded – one in Woolwich the other at Deptford – for the import of goods from exotic lands and for the use of the navy. Unfortunately, little remains from this period. The queen of James I, Anne of Denmark, blew winds of change by implementing a new architectural style from Continental Europe. The queen was known for dismantling wooden palaces built in the local style, and she demanded that Inigo Jones build the Queen’s House in 1616. This villa is in the first Renaissance style building in England and the earliest architectural work by Jones.

The wife of Charles I, Henrietta Maria, completed and decorated this construction and the son-in-law of Jones, John Webb, expanded the structure by building bridges that were designed to overcome problems caused by the London-Dover highway passing through the land.

Continental style

In exile in France, Charles II dreamt about building an English Versailles at Greenwich. He returned in 1664 and built an additional building by the river. Furthermore he brought André Le Nortre, the gardener of Louis XIV at Versailles, back with him for the sole purpose of outlining a plan of the park and making boulevards which reached towards the hills from the Queen’s House.

When William and Mary ascended to the throne, Greenwich was among their construction projects too. After his success in building a hospital at Chelsea, Architect Sir Christopher Wren was considered an excellent choice for designing and building another hospital for retired sailors, and was invited by the king and queen to undertake the project. To either side of the Queen’s House, he added wings, creating a U-shaped pattern. The hospital today is the University of Greenwich and is usually closed to visitors. The Painted Hall which was originally designed as a dining hall for sailors (and rarely used) can still be visited.

Maritime museum

The National Maritime Museum is the biggest maritime museum in the world and also one of the most beautiful museum complexes in the United Kingdom. It presents the navy, merchants, explorers and other relevant professions related to the maritime history of Britain, it also deals with subjects of global interest such as the voyages of discovery to the North Pole region, the mapping of the British Empire, the big migration to North America and the voyages of Captain Cook. On display are models of ships, paintings, medals, uniforms, maritime devices and many artefacts related to navigation. The most attractive of these artefacts are those taken from the ship the Mary Rose. Items such as the flagship of Henry VIII, which went down at Portsmouth in 1574, a painting depicting the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, a 12-metre long cubic formed black and white floor laid by Nicholas Stone in 1638 are among the most popular with visitors.

Royal Observatory

The Old Royal Observatory stands on the hill in Greenwich Park. Also known as Flamsteed House, it was built by Wren in 1675 for the first royal astronomer, John Flamsteed, and was used right up until 1948. Flamsteed originally planned the project, which was designed for Charles II and required 30 thousand observations, star investigations and perfect maritime maps. From the clock adjustment rooms, the ticking of the clocks could be heard, and a Time Cannon has been fired regularly at 13.00 hours since 1833, for passing sailors to adjust their watches by. Under the international agreement reached in 1884, Greenwich was accepted as a Prime Meridian. The Greenwich Meridian, passing through the court of the observatory, separates the eastern and western hemispheres from each other. For this reason all the clocks in the world are adjusted according to Greenwich.

On the same hill as the Royal Observatory stands a bronze statue mounted on a marble base of the famous British General James Wolfe (1727-1759) standing proud in his military uniform and gazing over London.

Park and Ranger

The 183-acre (74 hectares) park contains many beautiful, lush green trees, some of which remain from the garden arrangements made for Charles II by Le Nortre. Gnarled chestnuts, old cypresses, North American beeches and one leafy ash tree exude charm and majesty, and provide a fitting setting for the tulips across the well-shaped boulevards. From the Great Cross Avenue, there is a splendid panoramic view of the East End, London and Westminster. There is also a rose garden near the Ranger’s House, building of the Georgian period, within which hangs a Suffolk painting collection.

The Cutty Sark

Walking from the palace along the river to the east, you reach the Trafalgar Tavern near Trinity Hospital (established in 1613) and from there it is another short walk to the Cutty Sark pub, with its magnificent views of the slow-flowing tidal Thames. Moored outside, near the entrance to the tunnel below the river, is the Cutty Sark, the last and fastest of the nineteenth century “tea clipper” sailing vessels. The Cutty Sark travelled from China to England in just 99 days and later managed to arrive in London from Australia in only 72 days, loaded with wool. Today she is a tourist attraction. Another, smaller sailing ship is also on display here: the Gypsy Moth IV, in which Sir Francis Chichester circled the globe alone in 1966-67.

If at this point you become peckish you have the option of eating a traditional English pub lunch in the Cutty Sark, called a ploughman’s lunch. The Ploughman’s lunch consists of crusty bread thickly spread with butter, strong cheddar cheese, salad vegetables, pickle or piccalilli and perhaps some cold meat and of course a nice pint of beer or lager. If this is not to your liking, you can follow the English tradition of grabbing a light snack such as pork scratchings, crisps or salted peanuts.

Museum for fans

Behind the Nelson Road and College, near Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Alfege Church (1714), a Victorian covered market still stands. If any further proof were needed of the variety of Greenwich’s attractions, one need only visit the nearby Fan Museum, which traces the social history and graceful workmanship of the fan. The collection consists of 2,000 pieces of great beauty, quality and diversity, and is sheltered in two houses remaining from the Georgian period.

Arts:

Sıtkı Usta’s masterpieces

by Sibel DORSAN

Sıtkı Olçar, alias “Sıtkı Usta” (Master Sıtkı), creates artwork which glares, its colour, pattern and form giving new momentum to the traditional art of the ceramics of Kütahya. Perhaps due to the fruitfulness of the lands where he was born, or perhaps because of the “tile virus” cut into his heart in Kütahya – where everybody is moulded with this same virus – he has naturally turned towards this branch of art. It has not always been easy. When he first stepped into this realm with the “Ottoman Tile Workshop” in 1973, he experienced various difficulties. But he was to overcome this difficult artistic period thanks to much-needed help from his teachers, and the forbearance, sheer passion and love that he feels towards the profession which is now bringing him so much success.

His epithet, “the master”, is well-deserved, yet incomplete. Sıtkı Olçar’s first works were applications based on 16th and 17th century Iznik and Kütahya ceramics. From these he internalised the patterns of classical tile art, and breathed in its technique. But Olçar took one step further and brought his own interpretation to the time-honoured form. From the 1980s onwards, he constantly worked and searched for new ways to recreate the tiles of Iznik.

The artist learned the niceties of Iznik tile art from Faik Kırımlı, an authority on Iznik tiles famous for his work on the famous “coral red”, a colour which had been lost for 300 years. He went on to win much appreciation with his blue-white Iznik tile imitations based on archaic period forms. His reputation finally arrived in the international arena with the “Iznik exhibition” which he opened at the “Balkan Handicrafts Fair” in Volos, Greece, in 1986.

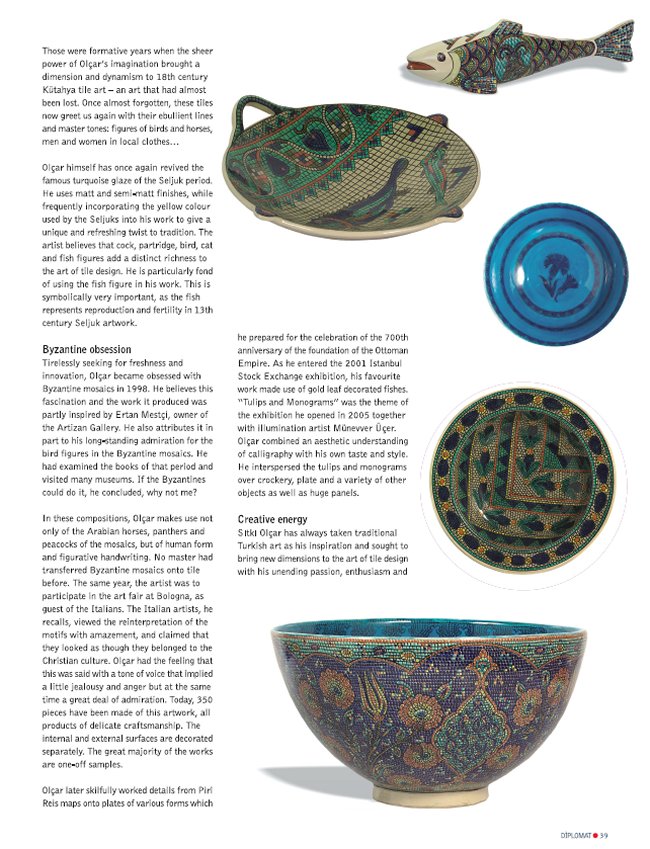

Those were formative years when the sheer power of Olçar’s imagination brought a dimension and dynamism to 18th century Kütahya tile art – an art that had almost been lost. Once almost forgotten, these tiles now greet us again with their ebullient lines and master tones: figures of birds and horses, men and women in local clothes…

Olçar himself has once again revived the famous turquoise glaze of the Seljuk period. He uses matt and semi-matt finishes, while frequently incorporating the yellow colour used by the Seljuks into his work to give a unique and refreshing twist to tradition. The artist believes that cock, partridge, bird, cat and fish figures add a distinct richness to the art of tile design. He is particularly fond of using the fish figure in his work. This is symbolically very important, as the fish represents reproduction and fertility in 13th century Seljuk artwork.

Byzantine obsession

Tirelessly seeking for freshness and innovation, Olçar became obsessed with Byzantine mosaics in 1998. He believes this fascination and the work it produced was partly inspired by Ertan Mestçi, owner of the Artizan Gallery. He also attributes it in part to his long-standing admiration for the bird figures in the Byzantine mosaics. He had examined the books of that period and visited many museums. If the Byzantines could do it, he concluded, why not me?

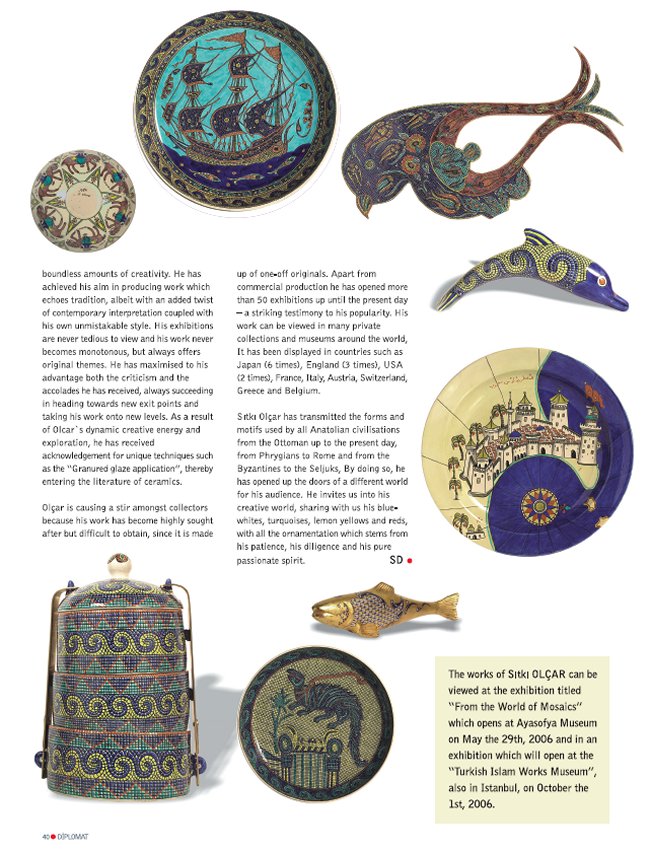

In these compositions, Olçar makes use not only of the Arabian horses, panthers and peacocks of the mosaics, but of human form and figurative handwriting. No master had transferred Byzantine mosaics onto tile before. The same year, the artist was to participate in the art fair at Bologna, as guest of the Italians. The Italian artists, he recalls, viewed the reinterpretation of the motifs with amazement, and claimed that they looked as though they belonged to the Christian culture. Olçar had the feeling that this was said with a tone of voice that implied a little jealousy and anger but at the same time a great deal of admiration. Today, 350 pieces have been made of this artwork, all products of delicate craftsmanship. The internal and external surfaces are decorated separately. The great majority of the works are one-off samples.

Olçar later skilfully worked details from Piri Reis maps onto plates of various forms which he prepared for the celebration of the 700th anniversary of the foundation of the Ottoman Empire. As he entered the 2001 Istanbul Stock Exchange exhibition, his favourite work made use of gold leaf decorated fishes. “Tulips and Monograms” was the theme of the exhibition he opened in 2005 together with illumination artist Münevver Üçer. Olçar combined an aesthetic understanding of calligraphy with his own taste and style. He interspersed the tulips and monograms over crockery, plate and a variety of other objects as well as huge panels.

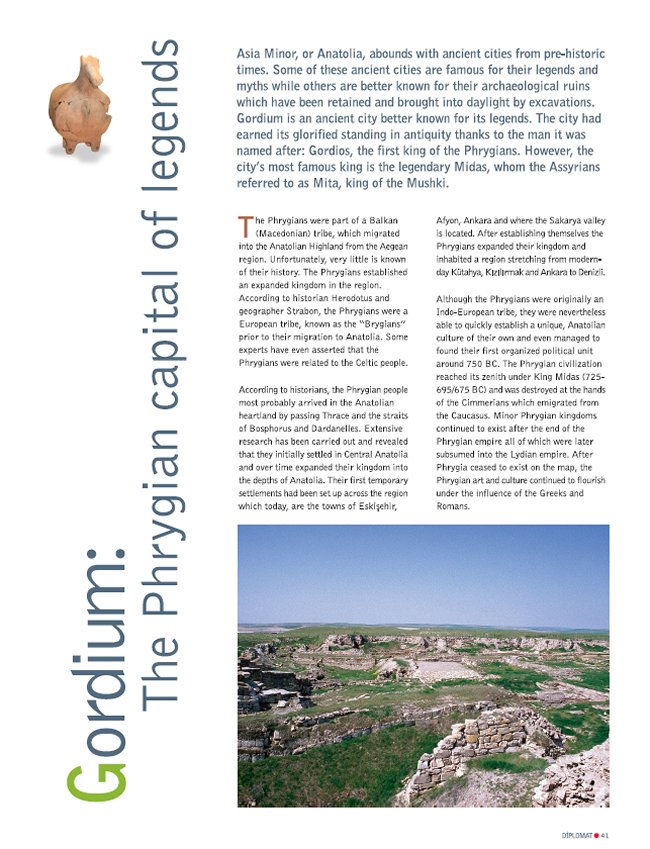

Creative energy