Project Description

18. Sayı

Quartet

DİPLOMAT – NİSAN 2006

18. Sayı

Diplomat

Nisan 2006

Diplomatic activity was as intense in March as it had been the previous month. Hawing visited Turkey’s western neighbour Bulgaria in February, President Ahmet Necdet Sezer travelled to eastern neighbour Georgia. Prime M inister Recep Tayyip Erdogan represented Turkey at the Arab League meeting in Sudan, and Speaker ol Parliament Bulent Arinc was in the Finnish parliament. Meanwhile, Ankara welcomed a string of foreign guests, and the diplomatic community made the acquaintance of a new ambassador from the Republic of Korea.

Some of our readers have remarked that the content of DIPLOMAT is becoming richer and richer. Among those adding value to our pages this month is the Ambassador of Kuwait to Ankara, Abdullah al-Duwaikh, who appears on the Interview page. The highly experienced ambassador answers DIPLOMAT’s questions not only on ties between Turkey and Kuwait but on topical issues related to Iraq and Iran, and on his country’s oil price policy.

Another guest in this edition is Polish Ambassador to Ankara Grzegorz Michalski. An expert on Turkey, Ambassador Michalski has been coming and going since 1985, during which period he has represented his country at various levels. He draws some interesting parallels between Poland and Turkey as the latter prepares for full EU membership – a path also trodden by Poland within the past few years. In the light of his own country’s experiences, he has some keen observations and recommendations to make.

Our Speaking Out pages are once again devoted to a non-government organization. Dr. Akkan Suver, president of the Marmara Foundation, which is organizing the Eurasian Economic Summit In Istanbul in May, gives detailed information about the event This year, the conference will focus on energy, on commerce and industry, and on terrorism and security. High-level participation is expected from 31 countries. Some of our readers, too, may have the opportunity to attend.

Born in the year of the foundation of the Republic, artist Kayihan Keskinok was raised amid the excitement of those early years by educators who perceived the passage from monarchy to the Republic as a revolution. Today he is one of Turkey’s leading artists. The story of this typical product of the Republican regime is told on our arts pages this month, accompanied by some of his striking pictures.

Turning to travel, DIPLOMAT allows the reader to join a rapid tour of Morocco, an exotic North African country where Arab and European cultures live side by side.

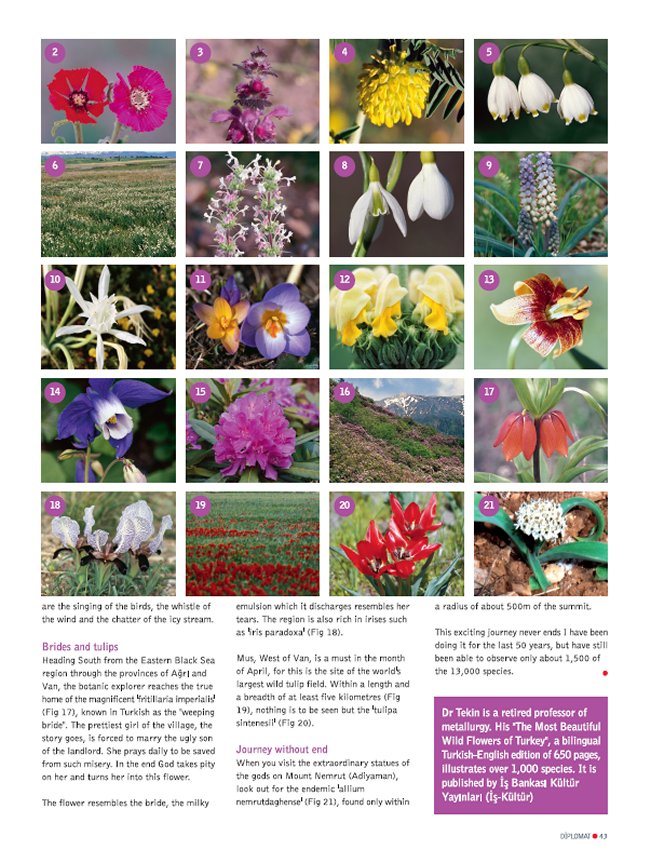

If you are unable to travel so far over the next few weeks, don’t forget how beautiful many rural areas of Turkey become at this time of year, as wildflowers carpet the entire land. You may be surprised to know that there are around 3,000 wild flowers indigenous to Turkey. Professor Erdogan Tekin presents a selection of them within these pages. So dont forget to take DIPLOMAT with you if you go out and about next weekend, and see if you can spot some of the wild flowers in our pictures.

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current opinion

Rethinking the Turkic world

by Hugh Pope

When Central Asia makes the headlines, it is almost always at moments of shock or bewilderment in the West. Last year, attention flashed in and out of focus on a barely controlled revolution in the Kyrgyz Republic, a bloody massacre in the police state of Uzbekistan and another wild swirl of coup rumors in Azerbaijan. Even in times of calm, perceptions of the Muslim states of the former Soviet Union have often reflected the world’s often superficial knowledge of the region: dire predictions of Islamic revolutions, fascination with the weirdness of rulers’ personality cults or fanciful legends of the riches of the old Silk Road.

There are certainly preposterous and scary sides of life in the Caucasus and Central Asia. But the caravan of history has moved a long way in the past 15 years. One of the Caspian Sea oil export pipelines initially dismissed as an absurd “pipe dream” will start pumping oil this year to the Mediterranean, bringing a useful 1% addition to world oil supplies. The vast and resource-rich country of Kazakhstan, lost in a hyper-inflationary spiral in the early 1990s, has raised its credit rating beyond that of Russia to equal that of states in eastern Europe. Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, waterlogged and bereft of color in 1990, now enjoys the buzz and overbuilding of its new status as an international oil boom city.

For sure, some of these ex-Soviet regimes are brittle. Most are insecure and undemocratic, being based on the former communist parties of the republics, which rightly fear they could be the victims of any true Central Asian common market or any pooling of political identity. Central Asian rulers therefore foster an artificial and prickly sense of national separateness to keep their peoples in bondage, as, say, has long been the case in the Arab world. And as elsewhere in the developing world, change is more likely to come through power shuffles within the ruling elites rather than bloody revolutions. But few now suggest — as many did in the early years after 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed — that these countries themselves will not survive intact. Although weak in themselves, most of the new states have succeeded in balancing the interests of superpowers around them. None will allow any of the others to take control of the region. For the first time in more than a century, Turkic states are free of any monopoly of external domination, whether by Russia, China or the United States.

New identities; a new world

The make-up of Central Asian populations and economies has also changed and new identities are being created. After 70 years of deliberate suppression by the rulers of the Soviet Union, and a half century of Tsarist restrictions before that, the world has now begun to hear of and accept as legitimate Turkic peoples previously thought to be utterly remote: independent nations for Uzbeks, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, and new, more autonomous status for groups like Tatars or Tuvans. Most of these new nations are inexperienced and fumbling forward along the pattern of developing nation states, rediscovering or making up new national myths and histories along the way. The process can look clumsy and even brutal to well-established states in the West. Nevertheless, there are at the same time other deeper developments that, from points of view of language, culture, history, have brought a new world into life since Moscow’s power over its southern periphery collapsed in 1991.

This tangle of uncoordinated elements, I believe, is leading to the emergence of a new and important Turkic world. Speakers of Turkic languages now number some 140 million people — one of the ten largest language groups on the planet. Self-conscious Turkey, which long saw itself as ‘the last independent Turkic state,’ has been joined by five Turkic fellows — Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic. The population of Tajikistan includes a large Uzbek minority, China has an awakening Uygur Turkic minority of at least eight million people (half of the population of its vast northwestern province of Xinjiang), and the mother language of perhaps one quarter of the population of Iran is Azeri Turkish — including the family of the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And the four million Turkish immigrants in Europe rival the numbers of the Irish.

Converging features

Despite Turkey’s commercial energy, the mineral wealth of the Caspian region and the strategic possibilities Central Asia, the Turkic world does not yet add up to the sum of its many parts. It is like the old Silk Road, whose many paths link the Turkic peoples between Asia and Europe, but which has never been one clear-cut highway. When the Soviet Union disintegrated, the United States, fearing instability, did fan a bout of Turkish-led enthusiasm about a new political dimension to the long-forgotten Turkic world. This brought about a heady series of meetings in the early 1990s at which presidents, professors and satellite television executives all tested the planks of what seemed to be a new Turkic platform. Concrete achievements were hard to pin down, but they influenced each other. Even now, when asked to cite a role model, President Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan still first cites Turkey’s Kemal Ataturk. But he, as with all leaders of Turkic states, is wary of any ‘big brother’ role for Turkey, which Ankara was never equipped to handle. Most Turkic communities and countries — including Turkey — have in practice followed Atatürk’s lead, eschewing any pan-Turkic adventure and giving priority to their own local national development.

Beneath the radar, nevertheless, convergence and familiarization continues on many fronts. A background drumbeat of Turkic meetings — which, it should be remembered, simply did not exist before — continues. Lip-service is always paid to Turkic brotherhood. The simple lifting of the Cold War barriers between Turkey and its old hinterland around the Black Sea and the gateways to the Turkic east has allowed a big rise in trade and tourist travel. Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and the Tatar Republic have all now switched to Turkish-style Latin alphabets, even if they are all slightly different. Languages like Uzbek and Azeri have replaced Russian as the official language, and are now developing fast. A new commercial region that focuses on Turkey’s dynamic metropolis of Istanbul has become well-established. International companies from Kodak to Morgan Guaranty Bank use Istanbul as a base to reach the east. When big contracts are awarded in the former Soviet Union — in Russia and the Turkic states alike — much of the subcontracting goes to nimble Turkish companies. In the Kazakh cultural and commercial capital, Almaty, five hours’ flight east of Istanbul, the leading new hotel is a brass-and-marble luxury spaceship that is Turkish-built, Turkish-managed, Turkish-catered and named after the Turkish capital.

The next generation

There is no question of any real Turkic political unity — and it’s worth remembering that in the past, such unity has only happened by chance under conquerors like the Mongol Genghis Khan or Tamerlane, a phenomenon unlikely to resurface today. In the Turkic east, Russian is still the language of business and political elites, and is likely to remain so for some years. And for Turkey, the relationship with Russia is many times more important than its ties with any one of the new Turkic states. But the changes set in motion in 1991 are slowly changing Turkic societies on the inside. Outside, there is growing acceptance of the word ‘Turkic’ itself: there is now even an American Association of Teachers of Turkic Languages, based in Princeton University and putting out colorful posters in U.S. campuses to attract students. Slowly, the idea of a Turkic world is becoming more meaningful to new generations, who, as these countries grow wealthier and more confident, will use it to help redefine themselves and their nations.

About the author

Hugh Pope has reported from Turkey, the Middle East and Central Asia for more than two decades. For much of the past decade he was the Istanbul bureau chief of the ‘Wall Street Journal’, covering events in the broader Middle East. His writing has appeared in the ‘Washington Post’, the ‘Los Angeles Times’, the London ‘Independent’ and the ‘Georgetown Journal of International Affairs’. He has lectured widely, including at London’s Royal Academy of Arts and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Pope is also the author of ‘Sons of the Conquerors: the Rise of the Turkic World’, an account of travels among Turkic peoples and communities from China to America. Published in New York, London and Istanbul in 2005, this book was selected as one the London-based ‘Economist’ magazine’s 45 “best books of the year”. More information and extracts are available at: www.sonsoftheconquerors.com

Born in South Africa in 1959, Pope was educated in Britain and received a BA in Oriental Studies (Persian and Arabic) from Oxford University in 1982. He is the co-author, with his first wife Nicole, of ‘Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey’, selected as a New York Times “notable book” in 2000. He is now preparing a new book on the Middle East.

Interview

Ambassador Al-Duwaikh: An optimist by nature

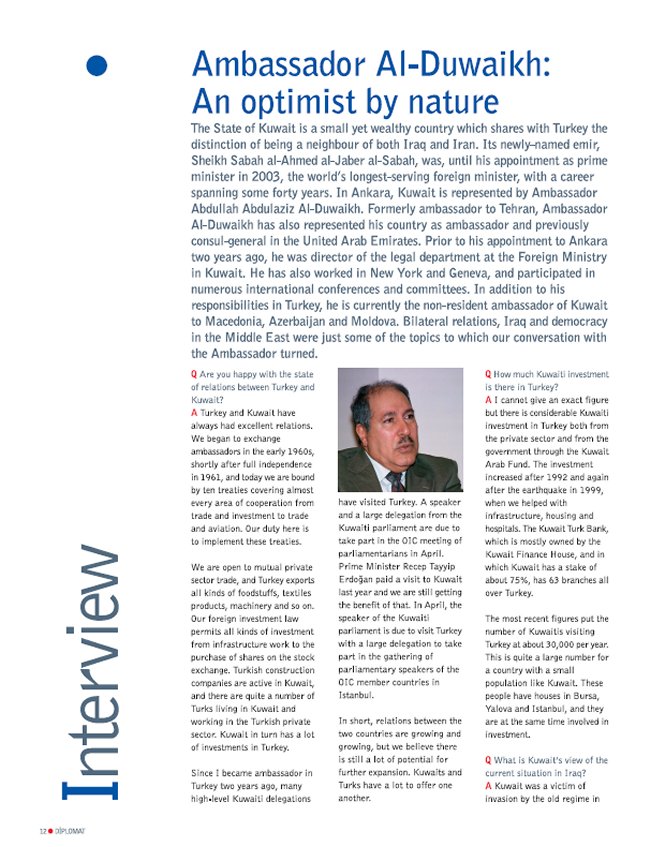

by Bernard KENNEDY

The State of Kuwait is a small yet wealthy country which shares with Turkey the distinction of being a neighbour of both Iraq and Iran. Its newly-named emir, Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmed al-Jaber al-Sabah, was, until his appointment as prime minister in 2003, the world’s longest-serving foreign minister, with a career spanning some forty years. In Ankara, Kuwait is represented by Ambassador Abdullah Abdulaziz Al-Duwaikh. Formerly ambassador to Tehran, Ambassador Al-Duwaikh has also represented his country as ambassador and previously consul-general in the United Arab Emirates. Prior to his appointment to Ankara two years ago, he was director of the legal department at the Foreign Ministry in Kuwait. He has also worked in New York and Geneva, and participated in numerous international conferences and committees. In addition to his responsibilities in Turkey, he is currently the non-resident ambassador of Kuwait to Macedonia, Azerbaijan and Moldova. Bilateral relations, Iraq and democracy in the Middle East were just some of the topics to which our conversation with the Ambassador turned.

Q Are you happy with the state of relations between Turkey and Kuwait?

A Turkey and Kuwait have always had excellent relations. We began to exchange ambassadors in the early 1960s, shortly after full independence in 1961, and today we are bound by ten treaties covering almost every area of cooperation from trade and investment to trade and aviation. Our duty here is to implement these treaties.

We are open to mutual private sector trade, and Turkey exports all kinds of foodstuffs, textiles products, machinery and so on. Our foreign investment law permits all kinds of investment from infrastructure work to the purchase of shares on the stock exchange. Turkish construction companies are active in Kuwait, and there are quite a number of Turks living in Kuwait and working in the Turkish private sector. Kuwait in turn has a lot of investments in Turkey.

Since I became ambassador in Turkey two years ago, many high-level Kuwaiti delegations have visited Turkey. A speaker and a large delegation from the Kuwaiti parliament are due to take part in the OIC meeting of parliamentarians in April. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan paid a visit to Kuwait last year and we are still getting the benefit of that. In April, the speaker of the Kuwaiti parliament is due to visit Turkey with a large delegation to take part in the gathering of parliamentary speakers of the OIC member countries in Istanbul.

In short, relations between the two countries are growing and growing, but we believe there is still a lot of potential for further expansion. Kuwaits and Turks have a lot to offer one another.

Q How much Kuwaiti investment is there in Turkey?

A I cannot give an exact figure but there is considerable Kuwaiti investment in Turkey both from the private sector and from the government through the Kuwait Arab Fund. The investment increased after 1992 and again after the earthquake in 1999, when we helped with infrastructure, housing and hospitals. The Kuwait Turk Bank, which is mostly owned by the Kuwait Finance House, and in which Kuwait has a stake of about 75%, has 63 branches all over Turkey.

The most recent figures put the number of Kuwaitis visiting Turkey at about 30,000 per year. This is quite a large number for a country with a small population like Kuwait. These people have houses in Bursa, Yalova and Istanbul, and they are at the same time involved in investment.

Q What is Kuwait’s view of the current situation in Iraq?

A Kuwait was a victim of invasion by the old regime in Iraq in 1990. Thank God, with the help of the UN and the coalition countries, Kuwait was liberated. We are also very grateful to the government and people of Turkey for standing up for the rights of Kuwait during and after the invasion. There was, I may add, nothing unusual about this, since Turkey has always supported the rights of the peoples of the world.

Even after liberation, the Saddam regime threatened Kuwait from time to time. So we thank God that the Iraqi people, with the help of the coalition, decided to change this regime. Of course, we hope that the situation in Iraq will become more settled. We would urge all countries, especially neighbouring countries, to help the Iraqi people and the new government of Iraq to overcome its difficulties. In this context, we share Turkey’s view that Iraq should remain a single entity. This would be good for Iraq as well as for all the neighbouring countries.

Q Are there still tensions and differences between Iraq and Kuwait? And are you worried that the Sunni-Shi-ite tensions within Iraq could affect other states in the region?

A We are in favour of the Iraqis taking their own decisions, and we are optimistic that they will choose the best solution to their problems. As for problems between the Iraqis themselves, these will affect other countries especially neighbouring countries, so we urge all parties in Iraq to be united and to join forces for the sake of Iraq and the Iraqis.

Q How have the Iraq situation and the nuclear issue affected Kuwait’s relations with Iran?

A We have always had warm relations with Iran and other countries in the region. We have several treaties with them. We think they can have some influence over some parties in Iraq, and we urge them to use their influence in the interests of Iraq. As for the nuclear issue, any conflict in the area will naturally affect us as the nearest country. We trust that all parties will handle the matter with care and that one day the problem will be overcome. We have enough problems in the region already.

Q How do you feel about democracy in the Middle East, given that in some cases it seems to have served only to radicalise politics?

A We believe that democracy is the ideal way of resolving issues in any country. Whatever the result, you have to respect it. If there had been a strong democracy in Iraq, Saddam would not have invaded Kuwait. In my country, Kuwait, democracy is well established. We have now also legislated for women to vote and take part in the elections to Parliament. The question of giving women a share in democracy was at the top of the agenda of the late Emir, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmed al-Jaber al-Sabah. This wish of his was implemented by the new Emir, Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, during his time as prime minister. Women have taken important roles in the economy and in education: we already have woman ambassadors and undersecretaries and we currently have a woman government minister. God willing, there will be many woman members of Parliament. At the same time, we respect the right of each people and country to decide for itself. Each people and government has to take its own decision.

Q Now for an easier question: what will become of oil prices?

A Actually, neither the members of OPEC nor the consumers want the price to go too high. Kuwait has always been in favour of reasonable solutions and consensus. But the oil price is established in the market and it is affected by many issues. As you know, Kuwait is currently the president of OPEC. The energy minister, Sheikh Ahmed Fahd Al-Ahmed Al-Sabah, is doing his best to ensure a price which is reasonable for all, whether producer or consumer.

Q Does Kuwait have a strategy for when the oil runs out?

A Yes, the former Emir put a strategy in place and we are getting results. In fact, it started more than 50 years ago. We created high investment authorities to invest part of the income from the oil revenues. When Kuwait was invaded, the government was able to pay a salary to all the people of Kuwait out of these investments. The Kuwaitis are very thankful to the former Emir for his vision of their long-term benefit. Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, the new Emir, is following the same strategy.

Q How do you find living in Turkey, and especially Ankara?

A Ankara is a place where we are able to work and live comfortably. But personally I don’t like traffic and crowded cities too much. If I didn’t have so many obligations, I would try to travel more. From time to time I have been in the Mediterranean region and the Black Sea region. There are a lot of things to be seen and visited – a lot of different traditions and landscapes; a great variety of food and climate. You need time to enjoy them all.

My best time I spend in nature. Turkey is provided with great natural assets, and it is up to us to see what God has created for the benefit of his people and to enjoy it. After all, as human beings, we too are part of nature. Every weekend I try to spend some time in natural environments, to take the view of the mountains, and so on. You do not have to go far from Ankara to do it.

I must say, wherever we go somewhere, we find the Turkish people very friendly and very helpful. This is the effect of the good relations between the two countries. They feel we are close to them.

Human angle

Southeast Turkey: undermining civilisation

by Prof. Dr. Özer OZANKAYA

One guiding thought of this column is that the structure of international relations as determined by the Western European states and the United States – the “Political West” – making use of gilded terms such as globalism, post-modernism or “the new world order” is based on the colonialism which has brought pain and poverty to humanity since the nineteenth century in its philosophy and in is practice. This structure prevents the world outside the “West” from forming democratic national societies. On the contrary, it encourages ethnic disintegration by supporting and encouraging forces and groupings of Middle Age character, such as religious organisations, tribes, clans, traditional landowners or dialect-speakers, which are aware that their existence would come to an end if a democratic national society were to emerge.

The second guiding thought of this column is that Atatürk has revealed, through the Turkish National War of Liberation and the Turkish democracy revolution, how this model can be defeated, and what guarantees can be put into place to prevent its re-occurrence. In this way, he has made an even greater contribution to civilization than Einstein, Pasteur, Rousseau, Humes or Marx. It is for this reason that the Norwegian nation has a maxim “Do it like Mustafa Kemal”, and that the people of Saigon filled the temples in commemoration of Mustafa Kemal on November 10, 1938. For the same reason, all efforts made to keep the foundations of the Turkish Republic our of sight and mind is extremely damaging to the accumulation of the human culture of freedom, social justice, peace and prosperity.

A case study

The PKK terror campaign, misleadingly referred to as the “Kurdish problem”, has been aiming to destroy the integrity of the Turkish homeland and the unity of the Turkish nation for the past 25 years. It is a case study which demonstrates the correctness of these two guiding thoughts. It draws on religious and local factors of oppression left over from the Middle Ages – such as pro-Islamism, religious sectarianism, the agha system of land ownership and tribalism. The attempt to separate one part of the Turkish Republic from the Turkish nation under the name of “Kurdistan” – an initiative which has never been carried out throughout history – is based on the falsehood that there is no united Turkish nation in Turkey, and that there is a separate, opposing people called the Kurds, who do not share the same territory as the Turks. On the divide-and-rule principle, it assists the Political West in its drive for oil and markets.

This terrorism may take on an artificial righteousness thanks to the racist and oppressive nature of some nationalist elements, as in Turanism. The so-called Nationalist Front governments of the 1970s and the so-called “Turkish- Islamic” policies of the subsequent September 12 administrations have both assisted the growth of separatist discord and disorder and provided it with a pretext for justifying itself. They have thus done grave damage both to the idea of the democratic Turkish nation on which the Turkish Republic is based and to the Islamic compassion which our people have embraced in the spirit of Yunus Emre and others.

Actually, all these domestic factors have received the direct and indirect support of the Political West, which displayed clearly 90 years ago with the Sevres project that it does not want Turkey to become a powerful political geography. As a retired US commander recently said of the September 12, 1980, military administration, “Our boys did it!”.

Defining the homeland

The land of the Turkish Republic is the land which was envisaged in the National Pact, rescued from foreign attacks by the Turkish nation and recognised at the international level through the Lausanne Peace Treaty. But if this Turkish homeland had not been based on historical, sociological, legal, cultural and moral values at least a thousand years old, the Lausanne Treaty, which constitutes its title deed, would not have been the sole international treaty which has remained unchanged in the world for the past 80 years.

Ever since the eleventh century, West Europeans have on their own maps defined the Anatolia which they would like to see carved up into units such as Armenia, Pontus or Kurdistan as “Turkey” (Turcomania, Turchia, La Turquie, Die Türkei) – and beginning from Southeast Anatolia. Both The Emergence of Modern Turkey by the renowned Middle East and Ottoman historian Professor Bernard Lewis and The Loom of History of Professor Herbert J. Muller point out that the Turcification of Anatolia was completed in the eleventh century. Now that the security which the Turkish Republic provided against the Soviet threat is being forgotten, however, attempts are being made to normalise the term “Kurdistan” and have it included in official and semi-official documents.

A former German chancellor regretted that Sevres had not been implemented. EU representatives, and diplomats and politicians from EU member countries, never tire of referring to Diyarbakır, where I was born and grew up, and a city which has produced the most elite elements of Turkish culture in every field, as the “capital of Kurdistan”. The Mayor of Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality, whose colours are increasingly obvious, is feted in the US and EU capitals, and the EU provides the Municipality with generous financial resources.

The civilised nation

At the beginning of the War of Liberation, on June 22, 1919, Atatürk easily defeated the efforts made to set up a separatist Kurdish government in Southeast Turkey with the aid of British weapons, money and “intelligence” and the open approval of the outdated Sultan-Caliph, demonstrating thereby that the Kurds and Turks were united. The Republic which he established made it possible for the whole nation to live peacefully together with honour, freedom and prosperity. Foreign attempts to provoke ethnic discontent among the sheikhs, sectarians and land-owners – bowed but not completely eliminated – continued during this period, but were never able to create a mass movement supported by citizens of Kurdish origin. This was possible because the concepts of the Turkish nation, the Turkish homeland and the Turkish state which constituted the basis of the Turkish Republic that emerged as a result of the Turkish liberation war were based on democratic definitions.

The Turkish nation was defined as “people of Turkey who are bound to the Turkish state through ties of citizenship”. People trusted that there would be no discrimination between the individuals of this nation as regards their origin, religion, sect, gender, class or occupation. The Turkish nation perceived itself as a society sharing a common history, country, ethics, language and name, with common feelings about the past and a sincere will to prepare for the future together. Folkloric subcultures were no replacement for science, art or technology, but merely the raw material for these. To remain trapped in folklore would be to leave a part of society at the level of ethnographic material that would feed the appetite of colonial forces. What a society needed if it was to live independently were a democratic political-legal administration, advanced science and technology, freedom of art, philosophy and science, and a developed written language. Only within the framework of this democratic Turkish nation concept could all sections hope to benefit from the secular – in other words, democratic – political, legal, educational, artistic, economic, technological, health and sporting opportunities of the contemporary age.

Voice of Atatürk

Atatürk, the architect of the democratic Turkish nation and the Turkish homeland, once argued that the members of the new Parliament were not only Turks, Circassians, Kurds or Laz, but a whole made up of all these. “There are citizens and compatriots within the political and social institution of the Turkish nation,” he noted, “who have been subject to propaganda with the idea that they are Kurds or Circassians or even Laz or Bosnians. However, these misappellations, which are the product of repressive periods of the past, have done no good for any member of the nation other than to cause misery, except for a few brainless reactionaries acting for the enemy. For these members of the nation have the same common history, morality and rights as Turkish society in general… How could the civilised Turkish nation, with its high morals, look sideways at the Christian and Jewish citizens among us, who have voluntarily tied their destinies and fates to the Turkish nation, or treat them as foreigners?”

The concepts of the democratic “Turkish nation” and the “Turkish homeland” nourished one another. Thus, no heed was paid in the new Turkish Republic to the ideas of expansionist universal Islamism, racist Turanism or irredentism (the recapture of territories of the Ottoman State which it abandoned through agreements prior to the World War I). In contrast, the idea of “Peace at Home, Peace Abroad” was firmly established. The “homeland” came to be a viewed as a concrete, common fatherland, the development of which was a responsibility towards all humanity:

“Nations are the real owners of the territories in their hands. But at the same time, they are the representatives of humanity on those territories. They take advantage of the rich resources of these territories themselves, and are consequently obliged to put them at the service of all humanity. In line with this principle, nations which are not capable of doing this should not have the right to existence and independence.”

Attack on humanity

According to Atatürk, “To set people fight at each other’s throats on pretence of making them happy is an inhumane and highly regrettable path. The only means to make people happy is the behaviour and force which enables to meet their material and spiritual needs mutually, bringing them closer together and making them love each other. The real happiness of humanity within world peace can only be achieved if the number of people with such supreme ideals grows and they are successful.”

On account of such views, the United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO) described Atatürk as an extraordinary revolutionary in the fields of education, science and culture, who had exerted great efforts on the path of international understanding, cooperation and peace, thereby setting a good example for future generations. I believe that any attack on Atatürk and on the Turkish Republic, the product of his Civilization Project, is one of the greatest evils that can be committed against humanity.

World view

Wars and Epidemics…in 1915

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV

In April 2006 we shall probably hear once more from some quarters abroad that the Muslim Turks “hurled their powerful armies on the peaceful and defenseless Christian Armenians”. We can also expect to hear dismissed as “Turkish propaganda” the view that much of the death in Anatolia occurred on account of epidemics. The facts would forcefully contradict both of these misleading assumptions. I have read and heard such statements often enough. Not only do Turkish and foreign documents refute them; a number of Armenian sources do so as well.

Less than a year ago, I was all ears when an American professor, who happened to be the director of a research center on genocide at Purdue University, told his audience that the Armenians, in the year 1915, were no more than weak, poor, unprotected and peace-loving women, children and old civilians facing the mighty weapons of the regular Turkish troops. The embarrassing but blatant truism is that the Armenian leadership formed large armies and fought against the Turks on several fronts under their own or Russian, French and British commanders.

Some Armenian sources, including the well-known UCLA professor R.G. Hovannisian, admit that their armies amounted to 150-160,000 soldiers plus guerillas, who were well armed with artillery and even war planes. H. Katchaznouni, independent Armenia’s first prime minister, states that they “were not afraid of war” because they thought they could win it. Their army “was well fed, well armed and well clothed.” He added: “The Turks proposed that we meet and confer. We defied them.” Their 1924 report to the U.S. Government (The Lausanne Treaty and Kemalist Turkey) quotes the appalling figure of “200,000 Armenians fighting as independent units or in the Allied ranks.” A 1926 report (The Lausanne Treaty, Turkey and Armenia) quoted an even higher figure: “more than 200,000.” This is 65,000 more than the number of U.S. fighting personnel present in Iraq.

Thirteen conflicts

Commanders like Gen. (Armen Garo) K. Pasdermajian published memoirs narrating exploits that include attacks, bloodshed, torture and pillage. There are more than enough references to Generals/Colonels Antranik, Areshian, Bakratuni, Dro, Hamazasp, Keri, Ossepian, Sebuh, Vardan, and others in the printed annals of Armenian writers like A.P. Hacobian and Gen. G. Gorganian. Some Armenian authors even asserted that the Allies owed their victory to the active belligerency of their armed people.

The Armenians indeed participated in the following wars or armed conflicts in the short but crucial eight years between 1914 and 1922: (1) the armed uprising behind the Turkish Eastern Front and attacks on military and civilian targets, (2) guerilla warfare in conjunction with the invading Czarist Russian forces, and organization into regular armies, leading to the forceful seizure of Van, (3) general armed challenge to the regular Ottoman Army, (4) armed Armenian occupation of parts of Eastern Anatolia after the Bolshevik Revolution and the withdrawal of the Russians, (5) armed conflict with Turkish Gen. K. Karabekir’s 15th Army-Corps, (6) Armenian massacre of Turks, Kurds, Circassians and other Muslims while retreating, (7) armed clashes with the forces of the Ankara Government, (8) Armenian armed conflicts with the Caucasian Azeris, (9) Armenian armed conflicts with the Caucasian Georgians, (10) armed conflict between the Communist and the non-Communisr Armenians, (11) Armenian belligerent association with the British in the Suez Canal, Sinai, Palestine and the Syrian Fronts, (12) Armenian belligerent association with the French forces in Adana and its adjoining territories, and (13) Armenian active support of the Greek armies invading Western Anatolia on 15 May 1919 and their opposition to the Turkish War of National Liberation.

The details of these wars appear in historical works, including those written by Armenian authors. The reports of the Russian officers Lieut.-Col. Tverdo-Khlebov, Capt. I. G. Plat and Dr. Khoreshenov and the scholarly works by Professors S. Shaw and R.F. Zeidner, may also be consulted. The statesmen and the commanders of the leading warring nations recognized their belligerency. Responsible Armenians, such Bogos Nubar, the head of the Armenian National Delegation at Versailles, officially wrote to the French Foreign Ministry that they had been “belligerents” during the war. To deny this wealth of material and confessions goes beyond mere disinformation.

Death by disease

The years 1914 and 1922 were also a period during which all of the inhabitants of Turkey had to live through war conditions. Many perished from hunger, cold, disease and epidemics. The mere mention of unsanitary predicaments is almost instantly chastised as propaganda supposedly downgrading the actual loss of Armenian lives. Turkish scholarship does not deny the war-time conflict with the Armenians, including bloodshed. But it offers documentary evidence in respect to its origins and development taking into account all aspects of the drama, not excluding the Armenian revolt, the massacre of Muslims and other realities of war.

One of these concrete phenomena was the loss of life among Armenians and Muslims on account of the epidemics. Fatal bacteria and viruses do not differentiate according to the ethnicity or religion of their victims. What had been true of all wars throughout history was also valid on the Anatolian scene.

In past centuries, the number of people, including soldiers, who died from disease was generally more than the number of those killed by bullets or bayonets at the fronts. Such casualties, mainly caused by typhus, reached the high figure of 2,350,000 during the Napoleonic Wars. Fighting armies and citizens were decimated by bubonic plague in the Ottoman-Russian War of 1828-29, by cholera and typhus in the Crimean War of 1854-56, and by smallpox in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. During the war with Spain in 1811-14, the British losses from disease were three times greater than their combat losses. In 1877-78, the Russians and Turks, like the French and Indo-Chinese during the former’s Tongking expedition, lost more lives to sickness than to weapons. In the American Civil War, the North suffered more casualties due to disease than to military engagements. The Spanish experienced the same during their expedition to Morocco. The American losses in the 1898 War with Spain were six times greater than the lives lost in actual combat.

The Ottoman experience

Conditions had improved in the developed Western societies in the eve of the First World War. Prophylactic measures and medical aid made it possible to control epidemics. Mass inoculations against cholera, typhus, and tetanus, the isolation of the sick with infectious diseases, the creation of many medical establishments, the introduction of a number of sanitary measures, and the development of transport considerably reduced the share of deaths from disease. Nevertheless, the Western countries continued to suffer. For instance, according to official figures (Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire) the British Army and Navy lost a total of 120,000 men from epidemics. The French losses totalled 179,000, chiefly from the Spanish flu. The Americans, late-comers to the active hostilities, lost 60,800 altogether. The Russian Army, which faced the Ottomans on the Eastern Front, lost 395,000 men. According to their official records (Wirtschaft und Statistik), the German casualties from diseases were 166,000. The other belligerents in both camps faced the same predicament.

The Ottoman Army losses were tremendous, the number of dead from diseases reaching figures unheard of in the 20th century wars. The German General Liman von Sanders, who acted as the inspector-general of the Ottoman armies, found the Turkish troops in a wretched state; some were even barefooted. American missionary-doctors (C.D. Usher and G.H. Knapp) recorded that the Turkish soldiers were “not protected from heat and cold, nor from sickness.” No less than 47% of the entire mobilized Turkish forces – of course only those able to reach a medical center – entered hospitals during those four years. Epidemics broke out, affecting not only Turkish military personnel, but also civilians – Turkish and Armenian.

Grave omissions

The heaviest toll was caused by malaria, followed by dysentery, high fever, typhoid, cholera, syphilis, tuberculosis, erytsipelas, and the like. Even Hafız Hakkı Pasha (the Commander of the Turkish Eastern Front and a son-in-law of the Ottoman Sultan), the German Gen. C. von der Goltz (the Commander of the Ottoman Army in Iraq), and Sir Frederick Maude (the Commander of the British Expeditionary Army in Basra) died of cholera or typhus.

The Armenians at the time were very much aware of that reality. Fear of epidemics and resulting death was one of the reasons for their refusal to give 3,000 Armenian soldiers to the Ottoman Army, among their Van inhabitants. As an Armenian author (M.G.) recorded in his book on the revolt in Van, they admitted that people “contracted diseases in the trenches.” The Turkish medical facilities could not do much, even for the Sovereign’s son-in-law.

Armenian participation in wars, during which they killed and were killed in return, and the loss of Armenian lives on account of rampant epidemics are both inseparable parts of the drama, but are usually omitted from present-day evaluations.

Grzegorz Michalski: A world of Poles and Turks

by Bernard KENNEDY

Poland’s Ambassador to Ankara has spent much of his career in Turkey, and he has not wasted the opportunity to make himself acquainted with just about every aspect of the country’s history, language and culture. At the same time, he has come to some intriguing conclusions about the Turkish and Polish nations, about dealing with the EU and about the diplomatic profession itself. The following summary of our long but never boring conversation also covers issues of culture, politics, business and security.

Grzegorz Michalski has a lot to say and acknowledges few limits on whether or how he will say it. What begins as an orderly question-and-answer session with Ankara’s ambassador to Poland soon swells to a flood of miscellaneous facts and observations. Topics float, sink and resurface as swiftly, unexpectedly and – almost – imperceptibly as the Ambassador switches from Turkish to English and English to Turkish. He expounds with unwavering enthusiasm on energy security and Turkey’s EU membership bid, on the Internet and the Embassy’s period furniture. One moment you are in 1414, when the Poles sent their first envoy (another Grzegorz: Ermeni Gregor), to the Ottoman court in Bursa; the next you are propelled forward to the era of unemployment and migratory labour, cartoon wars, NGOs and public relations. Nothing is unrelated to anything else in Michalski’s stream of consciousness; his train of thought has separate compartments neither for the generals and poets of the past nor for the tourists and plumbers of today.

Formative years

Ambassador Michalski’s career has, of course, coincided with a series of bewildering transformations in international relations – and not least in the country he represents. In central Europe, this period has lent itself to statements of optimism and leaps of faith rather than to diplomatic nicety or scientific disinterest. Nor has Turkey itself stood still since Michalski first visited in 1985, while preparing for his master’s degree as a Turkish specialist at the Moscow Institute of International Relations.

The ambassador was to return to Istanbul and Ankara for further work experience in 1987 and 1988, and went on to serve as head of the consular department and as culture and press attaché between 1990 and 1995. For Poles, this was a time of identity-building but also a moment of economic crisis: “In those days, a lot of Polish people used to come to Istanbul for the baggage trade. When they lost their money or their passports, they would come and plead with me at the Consulate, and we would help them as far as we could. Today when I fly back and forth to Warsaw, I see some of these same people in Business Class… How times have changed! We have left the baggage trade to others, and we are sending 250-260,000 tourists here for holidays each year.”

Ambassador Michalski was culture attaché, counsellor and eventually chargé d’affaires from 1997 to 2003, and was named ambassador in 2005. In the intervening periods, he pursued his other speciality, security policy, at the OSCE in Vienna and as minister-counsellor at the Foreign Ministry in Warsaw. Like many others who have lived at times of momentous change, he has a keen interest in history. On the one hand, he has been reading İlber Ortaylı’s ‘Osmanlıyı Yeniden Keşfetmek’ (‘Rediscovering the Ottoman’); on the other, he has been penning for the Embassy website (www.polonya.org.tr) ever-more Turkish-language information on the history of relations between the Poles and the Turks.

Plenty of history

Sometimes enemies, but often friends, the two nations share an archive which abounds in rather glorious gestures: the welcome extended by the Ottoman Empire to innumerable nineteenth century Polish exiles, military and civilian; the establishment of Istanbul’s famous Polish village ‘Polonezkoy’ in 1842; the Polish recognition of the Republic of Turkey, ahead of all other states, on the day before the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, and the refusal of President İnönü to hand over the Polish embassy to the Germans following their occupation of Poland in World War II. Michalski notes that it was mainly Christian and Catholic states – Russia, Prussia and the Hapsburgs – which partitioned Poland between 1772 and 1795, whereas the Ottoman sultans, caliphs of Islam, refused to recognise the 123-year division. Of national romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, who died of cholera in Istanbul in 1855, the Ambassador has this to say:

“He was a friend of Pushkin and Byron, who spent much of his years in France and Italy. His life is very similar to the contemporary notion of European culture. Turks are right to be proud that he died on their territory.”

By a happy coincidence, the first foreign visit of any minister in the new Polish government formed in late 2005 was the visit of Culture Minister Kazimierz Michal Ujazdowski to Istanbul, where he took part in the reopening of the renovated Mickiewicz museum. Michalski’s history lesson is by no means over: he is planning to reprint the catalogue from the Polish trade fair held in Istanbul in 1924, and he will continue to visit the grave of Ambassador Michal Sokolnicki, who refused to return to a Soviet satellite state after 1945, became a lecturer at Ankara University and is buried in Cebeci Cemetery.

Religion and politics

These rich veins of history are one source, according to the Ambassador, of the solid support lent by the Polish people to Turkey’s EU membership bid – the highest among the new EU member nations, he asserts. Polish backing also reflects the “moral obligation” to reciprocate Turkey’s backing for Poland’s membership in NATO. Like Turkey, Poland now stands on one of NATO’s longest borders; in future the two countries may also share a great deal of the EU’s periphery. Poles are thus aware of Turkey’s potential “geostrategic, geocultural and geoeconomic” contribution.

The Ambassador sees similarities of mentality too: “We are mainly a Catholic country… The late Pope John-Paul II was one of our best-known citizens. We know how important religious sentiments are. During the recent ‘cartoon wars’, the first European condemnation of the cartoons came from Prime Minister Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz. We respect the Turks and their religious beliefs because we want our own religious views to be respected…

“History has played many tricks on us. At times we have lost our independence or enjoyed only a semi-independence. As a result, we are very devoted to our state. When we entered the European Union, we were concerned about how much of our independence we were going to have to hand over. I observe that there are very similar concerns in Turkey. One of the most important messages which I would like to get across to my Turkish colleagues is that the EU does not make very great demands on our independence. It does not look as if the EU Constitution will enter into force in the foreseeable figure in its current form. So membership of the Union, as far as I can see, will not call for as many changes in the concept of statehood as some circles in both Poland and Turkey claim. We will be members as countries, and there is not be much need to sacrifice our state or independence and hand over authority to Brussels after we have become members. This understanding seems to be common to both Warsaw and Ankara.”

Helping to negotiate

The Turkish and Polish also share a lack of prejudice, Michalski argues. “According to French official sources, France needs 3,000 plumbers. According to the same sources, the number who have gone there from Poland is 153. But political propaganda based on prejudice exerts a powerful negative influence. There is none of this in Poland. This is another common factor. Five hundred years ago, two nations opened their doors to the Jews. One was the Ottoman Empire; the other was Poland.”

The Embassy has received “thousands” of requests from Turkish organisations wishing to tap into their Polish counterparts’ experience of the EU accession process. The Agriculture Ministry has shown particular interest in how Poland’s large, diverse, privately-owned agriculture sector sought to cope with the free EU market and health standards. The Ambassador himself has recently lectured on topics as diverse as employment and EU funding for local government. He sees similarities between pre-accession Poland and pre-accession Turkey in terms of the structure of local government and the need for decentralisation of responsibilities. With respect to unemployment, he points to the joblessness which emerged as a result of the opening up of Polish agriculture to the free market and the restructuring of heavy industry. Despite receiving billions of euros of foreign direct investment every year, Poland, with a population of under 40m compared to over 70m for Turkey, is still battling with an unemployment rate of around 17%.

When it comes to negotiating tactics, Ambassador Michalski argues that Turkey can learn from Poland’s mistakes as well as its successes. “Maintaining public support for the EU process is a challenge. The problems come to the surface and people become scared and start to undermine the process. Communications between the chief negotiator and the media are therefore of vital importance… You have to be very honest… The direct relationship between the Prime Minister and the chief negotiator is very important because in the end it is the Prime Minister who has to reconcile the different ministries and groups… Ninety per cent of the negotiations are internal arrangements.”

Turkey’s EU prospects

The Polish envoy is a firm believer in EU membership for Turkey and, indeed, Ukraine, if the Union is to play a role in the global economy, to challenge the logic of the “clash of civilisations”, to enjoy greater cultural and social diversity and to prevent “intellectual degeneration” of Europe.” The “common basket of values”, he argues, knows no geographical limits, and any desire to limit the definition of Europe to certain countries is bound to be overtaken by circumstances. Just as Cracow was Europe’s cultural capital in 2000, so Istanbul can and hopefully will be in 2010. Turkish membership of the EU will also strengthen its energy security, an issue on which Poland has been taking the lead, having suffered serious disruption of its gas supplies due to problems in Belarus in 2002 and the recent 2006 Ukraine-Russian crisis.

Yet Michalski harbours no illusions about the EU’s current problems, or its need to absorb the last wave of members. He is familiar, too, with the doubts of Turks about the terms set for negotiations, more than 40 years after their ties with the EU began. Warning against nationalism on both sides, he adds that Polish membership of the EU was by no means a foregone conclusion:

“I recall that President Walesa was not very optimistic when he met President Demirel in Warsaw in 1993 and in Ankara in 1994. “It was difficult in the early 1990s to convince western politicians that it would be a mistake to leave the Central European countries in a grey sphere. There was no invitation; it was us who went knocking on doors.”

The Michalski prescription is positive messages from the EU on the one hand, and more people-to-people contact on the other. In the latter context, he notes that that Poland received 1,000 applications for education visas in the first half of 2005 alone – and not only from big cities but from all over the country. He also takes pride in his Embassy’s cooperation with the Turkish National Agency for EU funds.

PR partner

References to NGOs pervade the Ambassador’s conversation. He welcomes the growing number of civil society and charity organisations in Turkey, and has found ways of taking part in their activities. The Embassy buildings and grounds are well-suited to meetings, recitals, festivals and fairs, and NGO-organised events of this kind go ahead there almost every month. While the organisation furthers its charity aims, the Embassy takes the opportunity to get to know people and perhaps to introduce the visitors to some Polish musical culture less universally familiar than Chopin.

In its “multi-directional diplomacy”, targeting politicians, the public and professional and interest groups alike, the Embassy also makes maximum use of its website and free publications. Efforts to reach more people with the same, limited resources have resulted in some interesting innovations. Michalski explains:

“As a rule, the first ladies of the embassies are people who accompany the ambassador. That is a very conservative part of diplomatic life. The wives of diplomats are generally well-educated, and in our own countries they do a wide range of jobs in all areas of business and culture. In our Embassy we have partners who are experts in the theatre and in science. We even had one who was a doctor. So the question is how to absorb their abilities. Considering the new spirit of enterprise in Poland, I asked my minister to grant a special dispensation for my wife to be employed at the Embassy. Like me, Edyta Michalska has an MA in political sciences and international relations. During our last spell in Poland she also studied public relations. She speaks Turkish as well as English, Portuguese and Russian. So she is now working with two hats as ambassador’s wife and as part-time employee in our culture – promotion office.”

Trade and security

One of the roles of diplomats, Michalski agrees, is to clear the path for economic relations. Political and cultural exchanges at the highest level were finally succeeded last month by an official visit to Turkey from a Polish economy minister, Pawel G. Wozniak. In the past fifteen years, Poland may not have solved its unemployment problem but it has absorbed over US$80bn of foreign investment and sprouted new industries and technologies. Decades ago, Poles were responsible for power plants, roads, tunnels and shipbuilding facilities in Turkey. Today, nascent Polish capital is sniffing around the electricity, gas and pipeline companies. The participation of Poland’s PKN Orlen in one of the consortia that bid for in the TÜPRAŞ refinery privatisation last year may be a sign of things to come. Meanwhile, the mutual volume of trade has jumped to US$2.5bn following Poland’s entry into the EU. Cleary, the relations which Michalski has forged with Turkish business leaders over the years are starting to bear fruit.

Needless to say, the Ambassador is equally eloquent on security affairs. He believes that NATO in its “hard and soft dimensions” has helped to keep Europe together and to suppress some of its historical tendencies. He sees no incompatibility between its continuing role and European security policy. The debate on future out-of-area NATO operations is a natural reflection of contemporary challenges, and disagreement is more about details than principle. The EU can take a role in preserving security, but “It is not only the Polish experience that you can only achieve your security in conjunction with others… And, yes, we need to contribute to peace outside Europe.”

In this spirit, Poland has offered troops for the EU mission to Darfur, while preparing to assume command of the ISAF in Afghanistan in 2007. Michalski argues that Poland’s troops in Iraq are not an occupation force but a stabilisation force. Poland is commanding a force of soldiers from more than a dozen nations, stationed in the centre of the country. A final note from the annals of bilateral history: Poland’s former military attaché to Ankara, General Andrzej Tyszkiewicz, was the first to command this force.

Morocco: Citadels of surprise

Text and photos: Ass. Prof. Dr. Fatih Müderrisoğlu, Research Ass. Ünal Araç

The West of the East; the North of the South… Morocco is one of those countries with an atmosphere completely its own. In August, 2005, Professor Aykut Mısırlıgil, Assistant Professor Fatih Müderrisoğlu, Research Assistant Ünal Araç and Dr. Selçuk Mısırlıgil set out from the small but charming Spanish port of Tarifa to see as much of medieval and modern Morocco as possible within the space of eight days. They came back with lasting memories, beautiful photographs and the following city-by-city report.

We thought of it as a return visit. Almost 700 years ago, the Arab traveller Ibn Batuta toured the lands of Anatolia. A quartet from Anatolia now headed for his motherland. As our catamaran-type vessel danced with the giant waves of the Strait of Gibraltar, we also called to mind the Arab commander Tariq Ibn Ziyad, who made the crossing with his army in the eighth century, and whose name was later given to “the Rock”. An exhilarating 40-minute journey is all that separates Europe and Africa at the point where the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean meet. Between the European and Arabian cultures, the narrow strait forms a broad geographical border

The looming coast and visa procedures conducted on board foretold our imminent arrival at the port of Tangier. Tangier was founded by Phoenicians in 1000 BCE. It was the birthplace of Ibn Batuta, and today ships come and go regularly from Spain, France and Italy. The citadel city or ‘Medina’ is in sharp contrast to the European-built ‘Ville Nouvelle’. In the former, the Kasbah, the administrative centre, and the soukh or bazaars, are sights not to be missed. Artists as diverse as Delacroix and Matisse have been influenced and inspired by the natural and cultural assets of Tangier.

Thus the scene was set for a tour of Moroccan cities which would also take in Fes, Meknes, Rabat, Casablanca and Marrakesh. All would display Western and Eastern characteristics in varying proportions, typically in quite separate quarters. Everywhere we met large numbers of children.

The rhythms of Fes

Railways take pride of place in Morocco’s transport network. Trains travel daily in both directions between the major cities, and are popular with the local people. Travelling by train left us better acquainted both with the country’s geographical features and with its people.

Fes is one of Morocco’s UNESCO world cultural heritage sites. Still considered the cultural capital of Morocco, it is the city which still best reflects the commercial, cultural and social life of the Arab world of the Middle Ages. The ancient urban texture of the medina gives it a very special atmosphere enhanced by palaces, gates, soukhs and mosques – and above all by the madrasahs, at one time a match for the greatest universities of Europe.

How many people in this city are consumers and how many producers? The thousands of shops and masses of shoppers made us wonder. In the narrow streets we also came across a living tradition centuries old: a circumcision procession, the boy and his father riding up front on a horse, followed by their relatives, to the rhythmic accompaniment of percussion and wind instruments the likes of which can only be seen in Africa. Moroccans are sincere, warm people. But we were sometimes disturbed by the heaps of garbage lying here and there.

Glimpses of empire

Meknes gave us another typical medieval welcome: narrow streets; mosques – which non-Muslims are not usually allowed to enter, and peddlers, particularly water peddlers, in their traditional costumes. At the square called the Kubbe (Dome) stands the grand reception hall where envoys to the royal palace were received. Adjacent to it are flights of steps which lead down to the dome-roofed cells of the dungeon.

From Meknes, we took cabs to another UNESCO site: the typical Roman city of Volubulis, complete with temples, administrative buildings, main streets, an advanced water system, an olive oil factory, baths and houses with mosaic floors. The city developed as a Roman military garrison boasting rich water resources and fertile lands. Its name is taken from a plant. This region is the greatest wheat and olive production centre in North Africa, and its products were once exported to the Roman Empire by land and sea. The dominant monument is a Triumphal Arch built in the central Forum in honour of the Emperor Caracalla.

Rabat and Casablanca

Rabat, the present capital, occupies a pleasant site on the Atlantic coast. The new settlement is extremely modern. The city museum, the Tower of Hassan and the old settlement outside the city wall, known as Cellah, proved well worth a visit. Cellah occupies a slope overlooking a broad river – a place of considerable natural beauty. Its history dates back to Roman times, and there was an Islamic settlement there by the twelfth century. Its mosque, dervish lodge, ruined minaret, shrines, gardens and pools suggest that it was an important place in years gone by.

Casablanca (“White House”) is much more than the name of a film. Like Turkey’s Istanbul, it is Morocco’s most crowded port and centre of entertainment and culture. There are large squares and tall buildings, a lively sea traffic, and kilometres of shoreline stretching along the Atlantic Ocean. Nowadays Casablanca is also famous as the home of one of the largest mosques of the Muslim World, built in the name of King Hassan II. The mosque has an asymmetrically planned praying area set in a broad courtyard right next to the Ocean. It is among the few mosques in the country which non-Muslims are permitted to enter. Given the sums spent on it, we felt that the Mosque could have been more striking in both its architecture and its ornamentation.

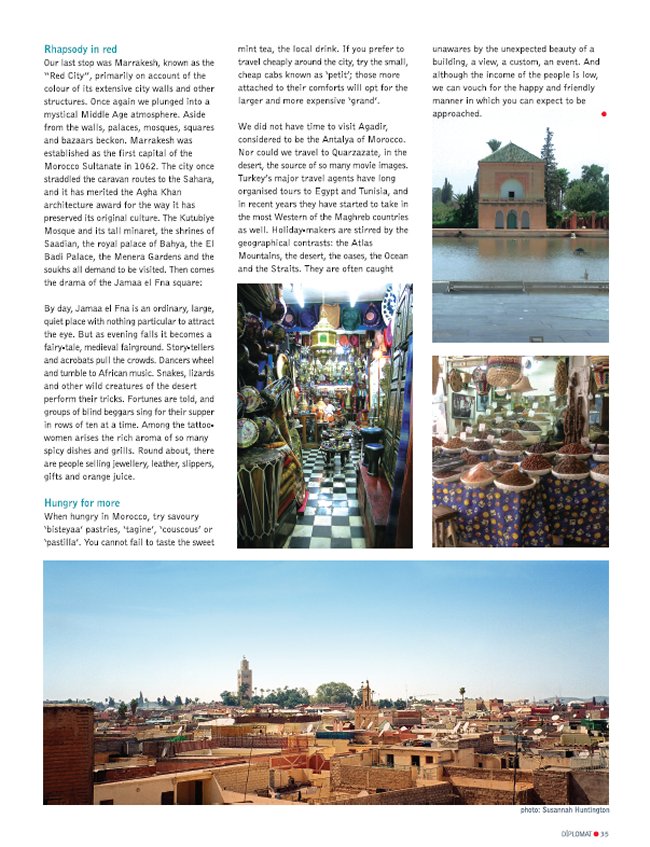

Rhapsody in red

Our last stop was Marrakesh, known as the “Red City”, primarily on account of the colour of its extensive city walls and other structures. Once again we plunged into a mystical Middle Age atmosphere. Aside from the walls, palaces, mosques, squares and bazaars beckon. Marrakesh was established as the first capital of the Morocco Sultanate in 1062. The city once straddled the caravan routes to the Sahara, and it has merited the Agha Khan architecture award for the way it has preserved its original culture. The Kutubiye Mosque and its tall minaret, the shrines of Saadian, the royal palace of Bahya, the El Badi Palace, the Menera Gardens and the soukhs all demand to be visited. Then comes the drama of the Jamaa el Fna square:

By day, Jamaa el Fna is an ordinary, large, quiet place with nothing particular to attract the eye. But as evening falls it becomes a fairy-tale, medieval fairground. Story-tellers and acrobats pull the crowds. Dancers wheel and tumble to African music. Snakes, lizards and other wild creatures of the desert perform their tricks. Fortunes are told, and groups of blind beggars sing for their supper in rows of ten at a time. Among the tattoo-women arises the rich aroma of so many spicy dishes and grills. Round about, there are people selling jewellery, leather, slippers, gifts and orange juice.

Hungry for more

When hungry in Morocco, try savoury ‘bisteyaa’ pastries, ‘tagine’, ‘couscous’ or ‘pastilla’. You cannot fail to taste the sweet mint tea, the local drink. If you prefer to travel cheaply around the city, try the small, cheap cabs known as ‘petit’; those more attached to their comforts will opt for the larger and more expensive ‘grand’.

We did not have time to visit Agadir, considered to be the Antalya of Morocco. Nor could we travel to Quarzazate, in the desert, the source of so many movie images. Turkey’s major travel agents have long organised tours to Egypt and Tunisia, and in recent years they have started to take in the most Western of the Maghreb countries as well. Holiday-makers are stirred by the geographical contrasts: the Atlas Mountains, the desert, the oases, the Ocean and the Straits. They are often caught unawares by the unexpected beauty of a building, a view, a custom, an event. And although the income of the people is low, we can vouch for the happy and friendly manner in which you can expect to be approached.

Speaking out

Dr Akkan Suver: A forum for Eurasia

Dr. Akkan Suver is the President of the Marmara Foundation, which is organising next month’s international Eurasia Summit in Istanbul, with a focus on regional energy issues, the role of small businesses and the fight against international terrorism. In the following commentary, Dr Suver explains the aims of the Foundation, the way in which the summit has developed over the years, the choice of topics, the other activities which will take place in and around the summit, and the dignitaries expected to attend. In his view, “Focusing on the EU does not mean that we should neglect Eurasia. Relations between Turkey and the Eurasian countries are weak, yet these regions have rich natural resources. It is not meaningful to be the poor steward of the rich resources in the Eurasia Region. We started out to discover new and broader ways of joining forces and cooperating.” The Foundation President concludes his remarks with some propositions on the concept of Eurasia itself.

The Marmara Vakfı (Marmara Foundation) was founded in 1985 with the aim of examining strategic issues and suggesting solutions to private and public institutions. It is a non-governmental organization. It carries out research, makes proposals, implements projects, discusses problems, handles enquires and helps to determine the public agenda. Our greatest goals are to develop “adoption strategies” by analyzing the effects of change, and to help non-governmental organizations so that they can play an important role in the development of democracy and the culture of civil society.

The Marmara Foundation is also the organizer of the annual Eurasian Economic Summit, which is now in its ninth year. The first summit was organized by the Marmara Group Strategic and Social Research Foundation eight years ago, with the attendance of just 6 countries. At that time I was the Secretary General of the Marmara Foundation. When I became president, we were on our way to staging the second summit. Gradually, these events have turned into a prestigious venture on the international stage. This year, the Ninth Eurasian Economic Summit will take place from May 8 to May 10, at the Assembly Hall of the Istanbul Chamber of Commerce in Istanbul.

Complementing the EU

Relations between Turkey and the Eurasian countries were as bright as a comet during the presidencies of Turgut Özal and Süleyman Demirel. The current government has focused on the EU, and has not given due consideration to the relations with the Eurasian Countries. But focusing on the EU does not require us to neglect the Eurasian countries. These regions still have rich resources and Turkey remains the poor steward of these rich resources. However the Turkish community and its youth have the strength and ability to make use of these resources. I believe that Turkey can take advantage of its identity to lead EU countries to this region.

I regard these summits as works undertaken to realize the goal set by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – namely, to achieve peace, stability and welfare for the region by cooperation among countries.

Every year we try to move one step further and realize the summits with a broader horizon. Last year, ten countries were represented at the Summit at the level of government ministers. Ninth President of Turkey Süleyman Demirel, Speaker of the Grand National Assembly Bülent Arınç, Ministers of State Kürşat Tüzmen and Nimet Çubukçu, Minister of Internal Affairs Abdülkadir Aksu, Minister of Industry and Trade Ali Coşkun, Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Hilmi Güler and Minister of Tourism Atilla Koç represented Turkey at the Summit.

Three key themes

This year, we have three themes. We will work on energy issue on the first day, trade and industry on the second day and finally international terrorism, internal, external and international security on the last day. The subtitles of the first day (May 8, 2006) will be: World’s Energy Need, Alternative Energy Resources, Energy Strategies of Eurasia-EU-USA-China-Japan, Geostrategic and Geopolitical Importance of EU and Eurasian Dimensions of Energy Strategies, Security Dimension of Energy: Future of Oil and Natural Gas Pipelines, and Security of the Turkish Straits.

On May 9, 2006 which is the second day of the Summit, we will be focusing on Trade and Industry. Under the leadership of the Small and Medium-Scale Industry Development Organization of the Republic of Turkey (KOSGEB) and its president Erkan Gürkan, we will draw a map for small and medium-size enterprises (SME’s) and introduce their performances to the representatives of foreign countries. Mr. Ali Coşkun, the Minister of Industry and Trade, will be attending this session just as he did last year.

To fill in a little more detail, we will touch on the following issues: SME’s – Pioneering and Leadership of KOSGEB, EU and UN Supported Funds and New Opportunities, Creativity, Relations Among the Economic Sectors, International Dialogue, Tourism and Congress, Meeting, Adventure, MASS, Leisure, Cultural and Belief Tourism: Alternative Tourism Options, Textiles, Ready-to-Wear Clothing, Home Textiles and Leather.

Finally on the last day of the Summit (May 10, 2006), we will turn to the crucial issue of ‘Globalizing Terrorism – Internal and International Security’. This issue will be discussed by high-level national and international authorities. It will be addressed under the following headings: Terrorism and Technology, Terrorism and Economy, Terrorism and Development, Cyber-terrorism (Terrorism and Science), Terrorism and International Cooperation, Terrorism and Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), The UN and the Fight Against Terrorism, and Security of Women: Social & Economic.

It is clear that under the insecure conditions it is not possible to talk about capital and investments.

Exhibits and messages

The summit will be accompanied by a number of other activities. As every year, under the leadership of the Süleyman Orakçıoğlu and the Istanbul Textile & Apparel Exporters’ Associations (İTKİB), we will organize a fashion show. This will provide a great opportunity for our foreign guests to view new horizons for the future.

This year, the Turkish Cooperation and Development Administration (TİKA) will make a major advertisement of Turkey’s mission and vision for the region and the countries in it.

During our cocktail party this year, the Turkey Bottle and Glass Factories will present unique examples of Turkish handicrafts.

In addition, Azerbaijan will be involved in a wide range of promotional activities. Azerbaijan will be particularly well represented at the summit at the highest level.

Invited guests

Altogether, we have invited to the summit ministers, chairmen of chambers and businessmen interested in making investments from Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Mongolia, Ukraine, Moldova, Lithuania, Estonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Austria, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, Macedonia, France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Syria, Tunisia, China, India, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, the United States and Israel.

At the time of writing, the following have confirmed that they will be participating in the summit: Ion Iliescu, the former President of Romania; Pal Csaky, Deputy Prime Minister of Slovakia; Heydar Babayev, Minister of Economic Development of Azerbaijan; Abbas Abbasov, Deputy Prime Minister of Azerbaijan; Hakim Soliyev, Minister of Economy and Trade of Tajikistan; Albert Chernichev, former Ambassador of the Russian Federation to Turkey; Charles Washington, Senior Policy Analyst of the US Department of Energy, Franc Urbancic, Coordinator for Counter-Terrorism at the US State Department; Ali Hasanov, Presidential Executive Staff for Political and Economic Relations of Azerbaijan; Abid Şerifov, Vice Prime Minister of Azerbaijan; Natıq Aliyev, Minister of Trade and Industry of Azerbaijan; Nazım İbrahimov, Minister of State of Azerbaijan; Irakli Chogovadze, Minister of Economic Development of Georgia; Jusuf Kalamperovic, Minister of Internal Affairs of Montenegro; Ehud Barak, former Prime Minister of Israel and member of the Parliament (Knesset); Lothar Klemm, former Minister and Member of Parliament of Germany; Colonel (Ret.) Jonathan Figel, Executive Deputy Director of the International Policy Institute for Counter Terrorism (Israel), and Dr. Alon Liel, the Director General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Israel. There are still several weeks to go until the Summit, and I am confident that we will receive many more confirmations, just as happened last year.

Defining Eurasia

Some comment may be called for concerning the definition of “Eurasia”. Is Eurasia a land-based civilization? Where does it start and end? Is it possible to make a geopolitical evaluation for the whole of Eurasia?

First of all, we have to know that in the strict sense there are only two countries which we can call Eurasian countries. These are Turkey and Russia. If we evaluate this concept in a narrow perspective, we cannot include either China or Kyrgyzstan, which would be an incomplete evaluation. It is necessary to treat the concept in relation to notions of “belonging” and “civilization”.

According to some, the values of the Atlantic and Eurasia cannot be reconciled. These people argue that the Atlantic is a sea-based civilization whereas Eurasia is a land-based civilization. Thus the two civilizations appear in opposition to one another. However, in the philosophy of civilization there must be togetherness and complementariness.

When talking about civilization, we must mention endurance and tolerance, not contradictions. Consequently, the philosophy of Eurasia reflects harmonization from the Atlantic seaboard to America and from the geography of Africa to that of Australia. It would not be correct to limit the philosophy of Eurasia to a triangular region with China, Russia and Turkey as its sides. This is not a cultural movement but a standard for civilization.

Pioneering common values

In short, we should not evaluate Eurasia just as a land based civilization and present it in opposition to other civilizations. Nor should its philosophy be restricted to Russia and Turkey alone. Accordingly, we have opened the horizon of the Eurasian Economic Summits to all the other four continents. We gather people and cultures from America, Africa and Europe together with Eurasia.

Eurasia is a standard of civilization. And civilization is the common value of the human being. This is what we are pioneering.

Arts:

Kayıhan Keskinok: The spirit of the Republic

by Sibel DORSAN

The plane tree is large, long-lived and resistant to the elements, providing ample shade and greenery year after year. This year’s winner of the “Plane Tree of Art Award”, presented by the Ankara-based ‘Dünya Kitle İletişim Araştırma Vakfı’ (World Mass Communications Research Foundation) is a painter the same age as the Republic itself – an important artist who has constantly renewed himself, and is still going from strength to strength: Kayıhan Keskinok. Keskinok received the award last month, during the 17th Ankara Film Festival, organised by the Foundation. He was described as a modern educator, who has raised countless students, a producer of hundreds of modern works, an upholder of the principles of Kemalism, a responsible intellectual and a man of principle…

Born in İzmir in 1923, Kayıhan Keskinok has only praise for the efforts of the young Turkish Republic, declared the same year, in providing him with an artistic education that helped put him on a par with the contemporary painters of Europe. He has paid his debt many times over, not only as a teacher himself, or with his paintings on national themes, but with his art ‘per se’ in each of its many transformations.

It began in the second-to-the back row of a second-grade primary school classroom. Though younger and smaller than his peers, he chose this seat so that he could draw without being bothered. Then came the Adana Teacher Training College. Although he had dreamed of going to military school and becoming a pilot, the timeless death of his father had forced him to choose a profession which did not, in those days, require a long period of training. He later fulfilled his wishes, he notes, by taking glider training from the Turkish Aeronautics Institute, winning his wings and parachuting.

At the College, there were many teachers who had studied abroad. Keskinok recalls the encouragement of headteacher Mehmet Naci Ecer, who had studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and prepared his thesis on Montaigne, Design and sculpture classes with the artist Hasan Kavruk greatly developed his abilities.