Project Description

2. Sayı

Winter

DİPLOMAT – ARALIK 2004

2. Sayı

Diplomat

Aralık 2004

The “DİPLOMAT” team is very happy right now.

We were frankly delighted with warm welcome which the first edition of “DİPLOMAT” received from diplomatic community. Both the content of the magazine and its visual quality were widely appreciated. The number of subscribers is now increasing slowly day by day, and offers of co-operation are coming in from various embassies. In the months ahead, we will be including more analyses of international affairs by different commentators.

The first edition of “DİPLOMAT” contained an interview with the doyen of the corps diplomatique, Ambassador of the State of Palestine to Ankara Fouad Yaseen. This month, you will be able to read the views both of Ambassador Jonuz Begaj of Albania, one of the important states of the Balkans, and of Ambassador Kaldone Nweihed, one of the world’s most important oil states.

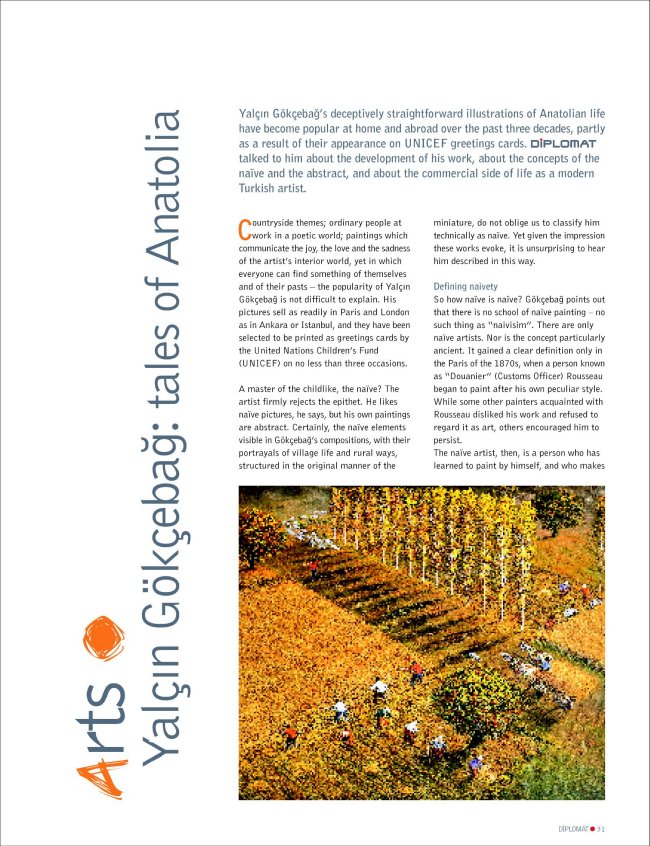

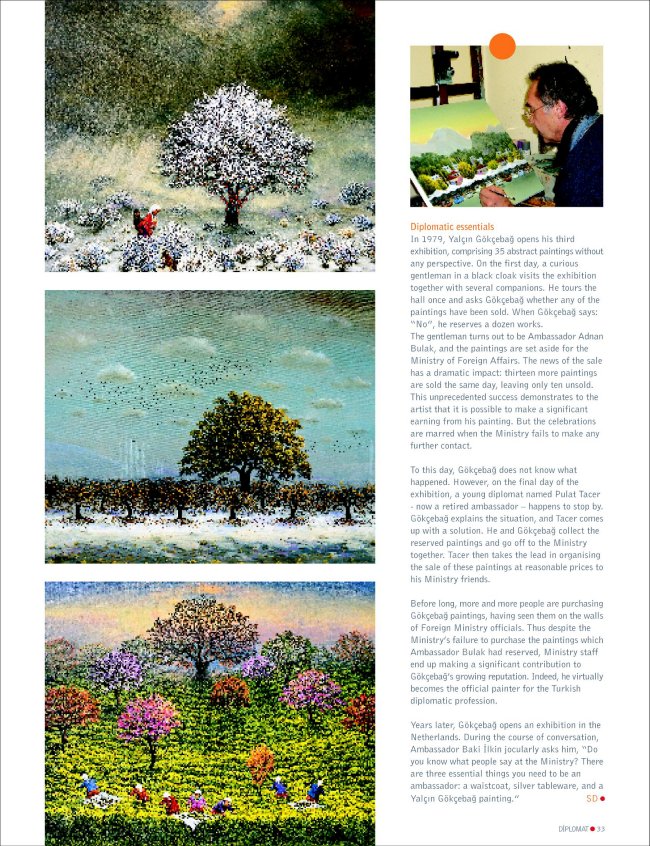

Many more interesting articles are to be found within these pages. Among those interested in arts and culture, an article about Yalçın Gökçebağ – one of the most popular modern Turkish painters – will, I think, attract particular attention.

It is a special pleasure for us to be able to report on the wide-ranging activities of the embassies in Ankara and to publicise them for the benefit of our other readers. Naturally, we can only report on these activities if we hear about them in time. We would therefore very much welcome any and all information which embassies are able to provide.

Meanwhile, it seems the winter has come to Ankara. Winters in Ankara are cold but when it snows they can be beautiful. Enjoy it and take care.

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current opinion

Watching Washington

by Bernard KENNEDY

The Turkish public would have preferred the US presidential election to go the other way. While top officials in Ankara did not necessarily share these sympathies, public perceptions of the situation in Iraq are likely to go on complicating the formation of workable policies.

The Turkish public would have preferred John Kerry to have won last month’s US presidential election. This was the overwhelming conclusion of opinion polls and casual observation alike. What the polls did not ask was why.

Turks had reasons of their own for wanting President Bush out. Mostly Muslim, they are particularly sensitive to the threat of a ‘War of Civilisations’ (or “crusade”). Moreover, Iraq and other potential targets of US military might are just next door – real, familiar people, rather than blobs on a strategic map. For all Turkey’s Western orientation, its social realities are in many ways closer to those of the South than the North.

If questioned, however, many would also have explained their desire for change in the White House with arguments equally familiar in Western Europe. That the US under Bush had responded with excessive and misplaced violence to the September 11 massacre. That far from making the world a safer place it was provoking extremism and terrorism. That it had disgraced itself in Guantanamao and Abu Ghraib. That its first-strike doctrine and unilateralism were unethical as well as a threat to the influence of other major capitals. That its real aim was to dominate the world’s oil supplies while nourishing the American arms industry. And so on.

Not that Kerry was expected to act otherwise. Abroad as well as at home, US presidentials are referenda on the incumbent. The hope was not that Kerry would win but that Bush would lose. Immediate foreign policy changes were never on the cards – a fact well-recognised and generally expressed in some such phrase as “It makes no difference who wins “. But if the US public refused to approve its administration’s bad behaviour, then belief in “justice” and “common sense” would be restored. And perhaps in the months and years ahead Washington might at least refrain from more of the same, lower its bottom line, and listen as well as talk.

Religious factor

This widespread Bush-aversion was broadly encouraged by media commentators, but was not totally shared in narrow ruling circles. Ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) aides were concerned that Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan might be unable to set up the same kind of cordial personal relationship with Kerry as he had succeeded in setting up with Bush. Militant Islamists may dread (or, alternatively, relish) the heightened influence of the Christian right in US politics. But for the AKP, a blurring of the distinction, in dominant international ideology, between religion and state (if not between religions and states) would be beneficial.

If, in the West, state laws come to accommodate religious precepts – and popes, patriarchs or preachers come to substitute for public officials, politicians and community leaders (not least on diplomatic occasions) – then Turkey’s semi-Islamist administration is all the more easily normalised. At a time when Western Europe shows signs of rediscovering secularism (in the face of Islamist militancy, of course), the US offers a more attractive, more comprehensible model to the AKP leadership. Like Bush, Erdogan has his millions of ‘honest folk” backers, who partake of his identity and admire his zeal, and who do not worry about much else.

Hawks for ever

In circulation at the highest echelons of the civilian and military bureaucracies, meanwhile, were a number of variations of the devil-you-know and climate-of-fear themes. One line of argument – not obviously borne out by history so far – was that a president in his second term, and hence more responsible to history than to the electorate, would make a more conciliatory and reliable leader and partner. To this must be added the atavistic assumption that interventionist US administrations are intrinsically more supportive of Turkey – whether in the context of European integration, at the IMF, or with respect to Cyprus and the matrix of Armenian issues. Dating back to the Cold War, this assumption rests compellingly on the understanding that Turkey’s importance to the US is largely military in nature, reflecting its role in NATO and its proximity to “enemy” territory.

The hawkishness-is-good-for-Turkey hypothesis is re-invented in the run-up to every US presidential election. The Cold War may be over; there may be no doves in sight, and Turkey-US relations may have blossomed into a strategic partnership (at least rhetorically) under the Democrat Clinton administration. Nevertheless, the hypothesis has yet to be disproved in the perceptions of the foreign policy establishment. If the Turkish press devoted few column centimetres to it this year, this is probably only a testimony to the general antipathy inspired by Bush’s policies.

The Iraq you know

Last but not least, policy-makers in Ankara privately take the view that while the Iraq situation is not good, it could be worse. The clock cannot be turned back, they note; the overthrow of the Saddam regime and the US occupation are matters of fact. In these circumstances, US policing and a gradual democratisation and legitimisation of the pro-US Iraqi government remain the best hope for law, order and economic opportunity. This requires a sustained US commitment to assign a large part of its military and economic capabilities to Iraq for the foreseeable future. The fewer compromises the US is prepared to make in order eventually to extract its troops, the better the prospects for the establishment of a strong and friendly neighbour in the near future. If the US presence requires co-operation with the Kurds of northern Iraq, then this is a penalty which Turkey has no choice but to pay, given alternative scenarios ranging from the establishment of a radical Shi-ite state to Arabs (and Turcomans?) taking bloody revenge on the Kurds, creating another massive refugee crisis in the Turkish Southeast and potentially cementing the case for an independent Kurdish state.

Limited leverage

With Kerry confined to history, Ankara clings to this logic, out of necessity if not out of conviction. By supporting Washington, top officials may also hope to exercise some influence over the future of Iraq. However, even if the US is interested in such bargains, the level and nature of the support that Ankara is willing or politically able to offer in return for its long shopping list – territorial integrity, no Kurdish state or autonomy, no Kurdification of Kirkuk, the disarming of the PKK – is limited. In terms of providing logistical support, the parliamentary vote of March 1, 2003, was a turning point. Turkey may still be of value to the US as a “model Muslim country”, but this does not represent a “card” that can be “played”.

Meanwhile, public opposition to the US in Iraq may increase further in the months ahead. For one thing, over 60 Turks have now been killed in lawless Iraq since the invasion. Almost as many Turkish lives have been lost as British, and all of them are the lives of non-combatants. Popular discontent is starting to be heard. The government in November warned citizens to avoid travelling to Iraq, but lorry-drivers are in need of the work, and government ministers, exporters and contractors are still eager for slices of the Iraq “cake”.

Eyes on Iraqi elections…

Secondly, this year has seen an increase in mine explosions and armed clashes in Eastern and Southeastern Turkey. These are inevitably associated in the public eye with the PKK Kurdish guerillas, now known as KADEK, and with their northern Iraq base. With the arrival of winter, the number of incidents is likely to fall, but another spate of funerals of conscripts in April or May could well spark nationalist recriminations against the AKP government.

Thirdly, the proposed Iraq elections will put the “Kurdish state” issue back on the agenda. A critical question will be whether elections are held in Kirkuk and other “disputed” settlements, and if so what the outcome will be. Aware as they are of the importance of transatlantic relations, neither the AKP leadership nor the Foreign Ministry nor the armed forces are impervious to public misgivings on these issues.

Human Angle

Anatolia’s Cultural Contribution to the European Identity

Prof. Dr. Özer OZANKAYA

Europe owes its central place in the world to the great advances which it has accomplished in the fields of art, science, technology, humanitarian philosophy and democratic socio-political order. All this is the outcome of a dialectical relationship between local and common cultural elements. This common European identity has been formed through continuous contributions of the peoples and regions of Europe and has in its turn guided and rescued them from sterile particularism and raised them above the folkloristic level to the level of arts and sciences.

Anatolia has been a part of this process for millenia, playing host to a succession of astonishing civilisations all of which have had a definite role in the evolution of European culture. So much so, in fact, that in many European languages the word ‘orient’ not only denotes what is lustrous and precious, along with the geographical East, but also means to establish one’s position (One does not “occident” oneself!).

Hittite heritage

Some 5,000 years before our time, the Hittites tilled the Anatolian soil, producing wheat and barley, and extracting and processing ores. “Their rulers,” says H. J. Muller in his The Loom of History, “were not divine or divinely appointed, but ruled rather as constitutional monarchs.’ They shared their authority with a council of nobles and warriors that supposedly represented the whole community, and queen mothers had a part in their prestige.

Arnold Toynbee has said that the cultural heritage of Anatolia remained predominantly Hittite down to Ottoman times. Unquestionably, they made a lasting impression. The immediate contribution of the Hittites was chiefly political. As they conquered they did not simply slaughter or enslave, but showed some genius for organisation and administration. They established a feudal empire that seemingly enlisted the loyalty of most of its diverse subjects by respecting their customs and according them some equity; the tablets found at Boğazköy contain traces of at least eight different languages. Hittites built a radiating system of roads, paving the way for the later Persians and Romans. (Muller, p.67)

In the third millennium the Hittites gave way to the Phrygians, who achieved a synthesis between the Anatolian and Mesopotamian traditions, as is most evident in their artefacts: reliefs and statuettes of ducks and rams; decorations and imagers engraved or painted on household utensils and woven into rugs. The harvest god Lityersis is a manifestation of the cycle of life, death and rebirth and pre-figures Christianity. After the defeat of the Persian Emperor Darius by Alexander the Great, the brilliant if hedonistic Ionian civilisation faded away, ushering in the classical epoch, and the coastal cities of Pergamon, Ephesos, Didyma, Assos and Miletos came to represent the heights of philosophy and arts.

In Ankara today there still stand, side by side, two monuments; the Temple of Augusts (Monumentum Ankyranum), with its columns and bath, and the memorial and mosque to the 15th century Turkish thinker Hacı Bayram. Here, cultures borrow viable, noble, productive elements from each other to work out a new synthesis.

Era of empires

From the 4th Century onwards, a succession of major empires held sway in Anatolia. The Byzantine Empire, a bridge of artistic and commercial exchange, was founded upon the cultural heritage of the ancient Anatolian civilisations. In its prime the empire was ruled by three Asiatic dynasties: the Assyrian, founded by Leo III (who was contemptuously called “the Phrygian”), the short-lived Amorian or Phrygian, and the so-called Macedonian, founded by Basil I, an Armenian born in Macedonia. (Muller, p.279). “A fresh impulse was needed,” writes Muller, “and it came from the East”.

During the iconoclastic period of the 8th and 9th centuries, the rock churches and homes of Cappadocia provided refuge to Anatolian Christians oppressed for depicting human faces. Historians believe that the main current of cultural influence at that time was from Cappadocia to Byzantium rather than the other way round, revealing a Cappadocian theme in Byzantine art and architecture.

The empire of the Seljuk Turks brought relief from persecution and the number of churches increased. A culture exempt from fanaticism and conscious of the beauty of consensus was rising. The philosophers of the period – Yunus Emre, Hacı Bektaş, Mevlana – are still loved and respected in Turkey, and have attracted recent international attention with their characteristic tolerance and humanity. The Seljuks built prosperous cities, medreses (colleges), hospitals, roads, bridges and caravanserais. Their arts used some Anatolian animal motifs such as the twin-headed eagle of the Hittites, while they fully developed and perfected all the characteristics of Islamic art – its use of colour and abstract ornament in metal and wooden objects, calligraphy, painted tiles, and architecture.

Ottoman contributions

The Ottomans, too, worked out a synthesis of the preceding cultures. They interacted intensively first with Venice and then with many other cities, states and lands to the West. All this is well-known and well-documented. But at the same time it is worth drawing attention to two figures from the Ottoman world of ideas: the poet Fuzuli and the writer İbrahim Hakkı.

Fuzuli is best known among Turks today for his sharp criticism of corrupt officialdom (“I offered them a greeting/ but still I was not welcome/ because it was no bribe”). His prime theme, however, was the exaltation of the truth. Although by “truth” he naturally refers to the truth of God, he gives a remarkable definition of science which emphasises the necessity of never-ending research: “To reach the highest ranks through science/ is an unattainable desire /For science is nothing but what we already know! /The most fundamental thing is love (of truth)”. There is a striking parallel here with the concept of science expressed by Justus von Liebig from 19th century Germany – “Science begins to be really interesting only when it no longer provides explanation”.

The propositions of Hakkı, a native of Erzurum, are perhaps even more striking. Hakkı is the author of the Marifetname , a study of science, philosophy and literature completed in 1756. Half a century before the birth of Darwin, he suggested that human beings were the outcome of a very long process of evolution, in which they were preceded by the monkey. Elsewhere in his famous study, Hakkı warns that:

“Whoever believes that it is a religious duty to dispute the reality of the facts stated here does nothing but enfeeble and invalidate the religion and commit a crime against it. For these facts are established through mathematical proofs. When one learns and verifies them and discovers their causes, time, quantity and prolongation, one would no more doubt the truth of them even if he were told they are against the religion. One would rather call the religion itself into question, asking oneself, ‘How could the religion ever go against the reason?’”

Republican revival

The Turkish Republic was founded upon this millennial cultural heritage at a time when the East was flattened by colonialism and the West was suffering from “a pure organic disintegration and a pure mechanical organisation” – to quote from English author D.H. Lawrence. The Turkish Republic is a comprehensive project of civilisation saving the Turkish people from both types of decline and opening up for them the vistas of arts and science, representative government, individual freedom, female emancipation, human rights and supremacy of law. It implies both peace between nations, in which colonialism is eradicated, and deliverance from materialist obsessions, moral sterility, social stagnation and intolerance. And above all it seeks to meet both the political and economic requirements of democracy.

The project of civilisation enhances a culture which integrates the local with the general and inspires the preservation and development of both. One of the first steps taken by the Republican regime was to determine and disseminate the cultural values of Anatolia. The Anatolian cultural heritage was put at the service of the national and international community through the founding of modern universities, academies, museums, libraries, archives, exhibitions and excavations. Meanwhile, many aspects of Turkish culture were elevated above the former folkloristic level and acquired the form and content of opera, ballet symphonic music, painting, sculpture, cinema, broadcasting and literature. In art and science as in the realm of political and social systems, Anatolia continued its role in the European synthesis.

Magical minerals

By Sibel DORSAN

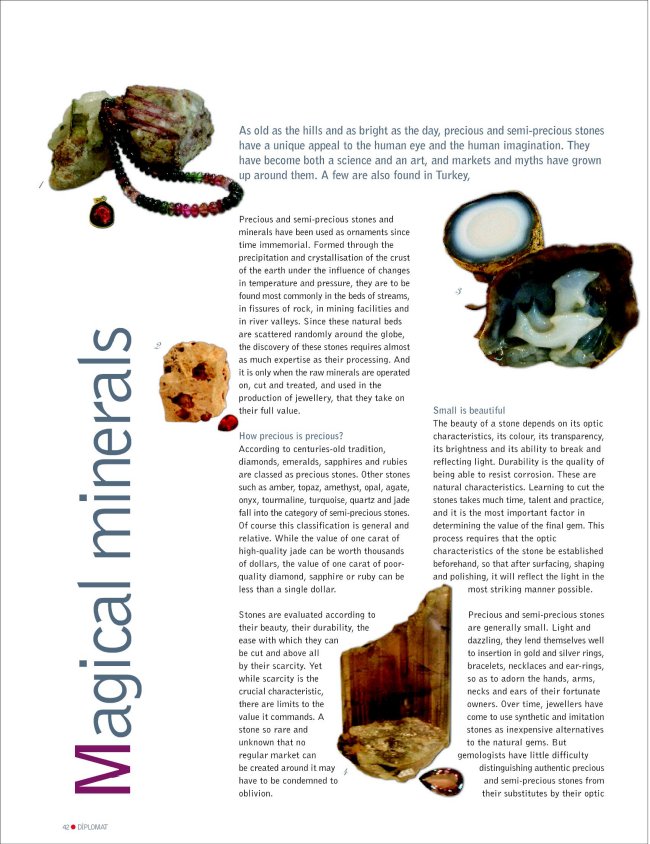

As old as the hills and as bright as the day, precious and semi-precious stones have a unique appeal to the human eye and the human imagination. They have become both a science and an art, and markets and myths have grown up around them. A few are also found in Turkey.

Precious and semi-precious stones and minerals have been used as ornaments since time immemorial. Formed through the precipitation and crystallisation of the crust of the earth under the influence of changes in temperature and pressure, they are to be found most commonly in the beds of streams, in fissures of rock, in mining facilities and in river valleys. Since these natural beds are scattered randomly around the globe, the discovery of these stones requires almost as much expertise as their processing. And it is only when the raw minerals are operated on, cut and treated, and used in the production of jewellery, that they take on their full value.

How precious is precious?

According to centuries-old tradition, diamonds, emeralds, sapphires and rubies are classed as precious stones. Other stones such as amber, topaz, amethyst, opal, agate, onyx, tourmaline, turquoise, quartz and jade fall into the category of semi-precious stones. Of course this classification is general and relative. While the value of one carat of high-quality jade can be worth thousands of dollars, the value of one carat of poor-quality diamond, sapphire or ruby can be less than a single dollar.

Stones are evaluated according to their beauty, their durability, the ease with which they can be cut and above all by their scarcity. Yet while scarcity is the crucial characteristic, there are limits to the value it commands. A stone so rare and unknown that no regular market can be created around it may have to be condemned to oblivion.

Small is beautiful

The beauty of a stone depends on its optic characteristics, its colour, its transparency, its brightness and its ability to break and reflecting light. Durability is the quality of being able to resist corrosion. These are natural characteristics. Learning to cut the stones takes much time, talent and practice, and it is the most important factor in determining the value of the final gem. This process requires that the optic characteristics of the stone be established beforehand, so that after surfacing, shaping and polishing, it will reflect the light in the most striking manner possible.

Precious and semi-precious stones are generally small. Light and dazzling, they lend themselves well to insertion in gold and silver rings, bracelets, necklaces and ear-rings, so as to adorn the hands, arms, necks and ears of their fortunate owners. Over time, jewellers have come to use synthetic and imitation stones as inexpensive alternatives to the natural gems. But gemologists have little difficulty distinguishing authentic precious and semi-precious stones from their substitutes by their optic and physical characteristics as well as their peculiar chemical structures.

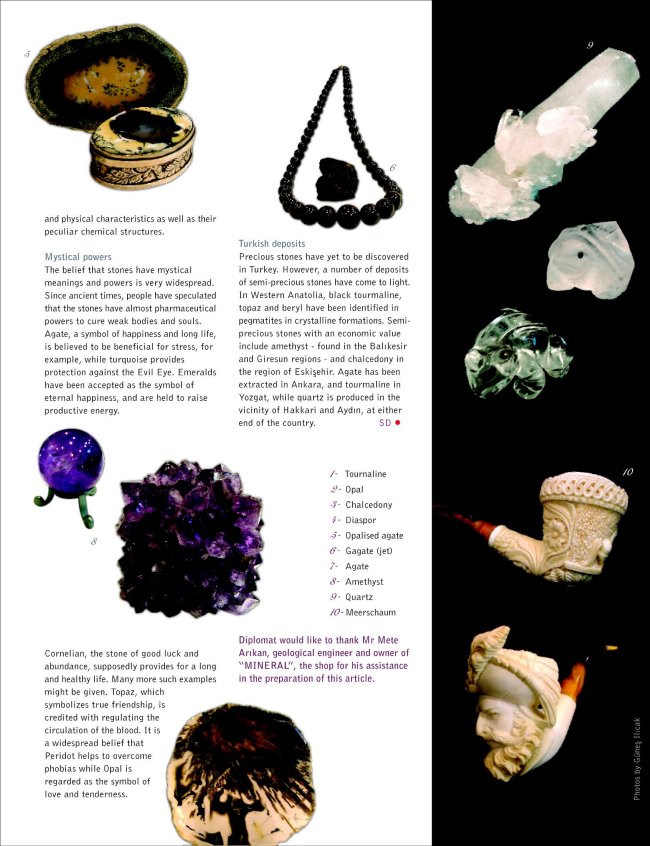

Mystical powers

The belief that stones have mystical meanings and powers is very widespread. Since ancient times, people have speculated that the stones have almost pharmaceutical powers to cure weak bodies and souls. Agate, a symbol of happiness and long life, is believed to be beneficial for stress, for example, while turquoise provides protection against the Evil Eye. Emeralds have been accepted as the symbol of eternal happiness, and are held to raise productive energy. Cornelian, the stone of good luck and abundance, supposedly provides for a long and healthy life. Many more such examples might be given. Topaz, which symbolizes true friendship, is credited with regulating the circulation of the blood. It is a widespread belief that Peridot helps to overcome phobias while Opal is regarded as the symbol of love and tenderness.

Turkish deposits

Precious stones have yet to be discovered in Turkey. However, a number of deposits of semi-precious stones have come to light. In Western Anatolia, black tourmaline, topaz and beryl have been identified in pegmatites in crystalline formations. Semi-precious stones with an economic value include amethyst – found in the Balıkesir and Giresun regions – and chalcedony in the region of Eskişehir. Agate has been extracted in Ankara, and tourmaline in Yozgat, while quartz is produced in the vicinity of Hakkari and Aydın, at either end of the country.

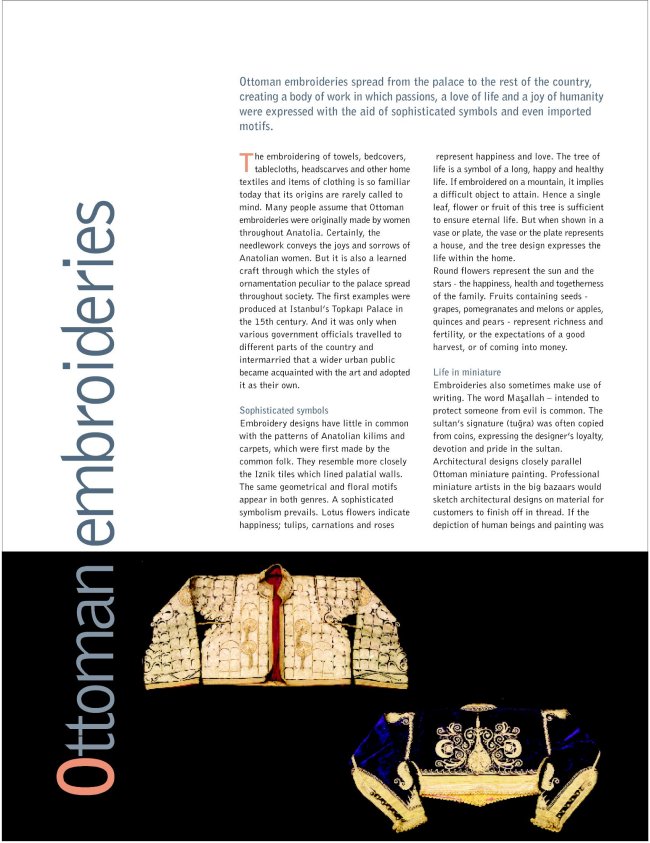

Ottoman embroideries

by Alper YURDEMI

Ottoman embroideries spread from the palace to the rest of the country, creating a body of work in which passions, a love of life and a joy of humanity were expressed with the aid of sophisticated symbols and even imported motifs.

The embroidering of towels, bedcovers, tablecloths, headscarves and other home textiles and items of clothing is so familiar today that its origins are rarely called to mind. Many people assume that Ottoman embroideries were originally made by women throughout Anatolia. Certainly, the needlework conveys the joys and sorrows of Anatolian women. But it is also a learned craft through which the styles of ornamentation peculiar to the palace spread throughout society. The first examples were produced at Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace in the 15th century. And it was only when various government officials travelled to different parts of the country and intermarried that a wider urban public became acquainted with the art and adopted it as their own.

Sophisticated symbols

Embroidery designs have little in common with the patterns of Anatolian kilims and carpets, which were first made by the common folk. They resemble more closely the Iznik tiles which lined palatial walls. The same geometrical and floral motifs appear in both genres. A sophisticated symbolism prevails. Lotus flowers indicate happiness; tulips, carnations and roses represent happiness and love. The tree of life is a symbol of a long, happy and healthy life. If embroidered on a mountain, it implies a difficult object to attain. Hence a single leaf, flower or fruit of this tree is sufficient to ensure eternal life. But when shown in a vase or plate, the vase or the plate represents a house, and the tree design expresses the life within the home.

Round flowers represent the sun and the stars – the happiness, health and togetherness of the family. Fruits containing seeds – grapes, pomegranates and melons or apples, quinces and pears – represent richness and fertility, or the expectations of a good harvest, or of coming into money.

Life in miniature

Embroideries also sometimes make use of writing. The word Maşallah – intended to protect someone from evil is common. The sultan’s signature (tuğra) was often copied from coins, expressing the designer’s loyalty, devotion and pride in the sultan. Architectural designs closely parallel Ottoman miniature painting. Professional miniature artists in the big bazaars would sketch architectural designs on material for customers to finish off in thread. If the depiction of human beings and painting was forbidden by the sultan and caliph, embroidery offered a substitute medium of narrative and self-expression.

Noah’s ark

Tents, kiosks and ships generally reflected the royal lifestyle. At the same time, the ship design is the symbol of freedom. Birds and butterflies were most often used by nomads to represent happiness, good luck and freedom, while fish designs were popular near coasts and lakes and represented fertility, good luck and a good harvest. Other everyday animals also appear in the embroideries. Indeed, something resembling Noah’s Ark pops up at times – a part of Anatolian mythology. Whatever people talked about to their children they also reproduced in thread.

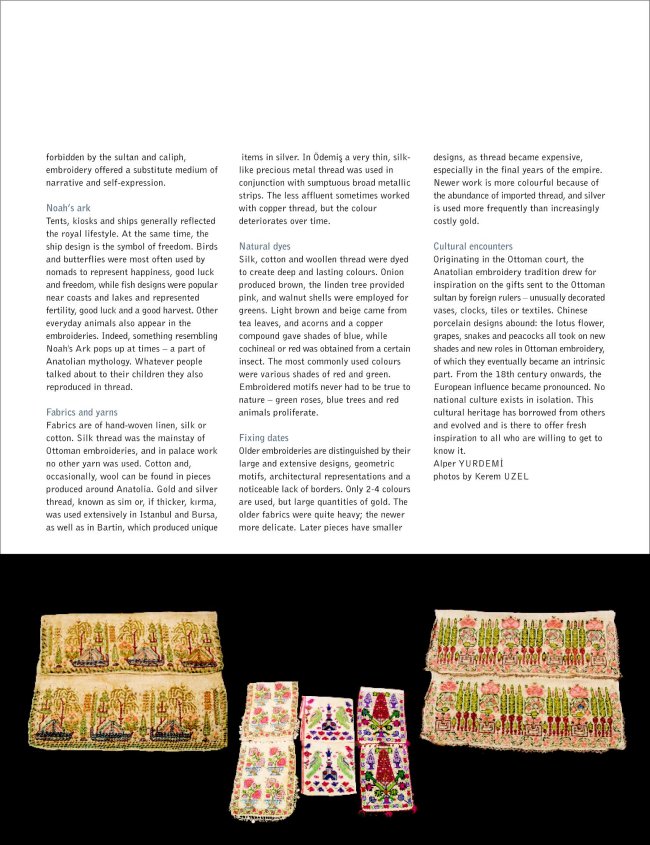

Fabrics and yarns

Fabrics are of hand-woven linen, silk or cotton. Silk thread was the mainstay of Ottoman embroideries, and in palace work no other yarn was used. Cotton and, occasionally, wool can be found in pieces produced around Anatolia. Gold and silver thread, known as sim or, if thicker, kırma, was used extensively in Istanbul and Bursa, as well as in Bartin, which produced unique items in silver. In Ödemiş a very thin, silk-like precious metal thread was used in conjunction with sumptuous broad metallic strips. The less affluent sometimes worked with copper thread, but the colour deteriorates over time.

Natural dyes

Silk, cotton and woollen thread were dyed to create deep and lasting colours. Onion produced brown, the linden tree provided pink, and walnut shells were employed for greens. Light brown and beige came from tea leaves, and acorns and a copper compound gave shades of blue, while cochineal or red was obtained from a certain insect. The most commonly used colours were various shades of red and green. Embroidered motifs never had to be true to nature – green roses, blue trees and red animals proliferate.

Fixing dates

Older embroideries are distinguished by their large and extensive designs, geometric motifs, architectural representations and a noticeable lack of borders. Only 2-4 colours are used, but large quantities of gold. The older fabrics were quite heavy; the newer more delicate. Later pieces have smaller designs, as thread became expensive, especially in the final years of the empire. Newer work is more colourful because of the abundance of imported thread, and silver is used more frequently than increasingly costly gold.

Cultural encounters

Originating in the Ottoman court, the Anatolian embroidery tradition drew for inspiration on the gifts sent to the Ottoman sultan by foreign rulers – unusually decorated vases, clocks, tiles or textiles. Chinese porcelain designs abound: the lotus flower, grapes, snakes and peacocks all took on new shades and new roles in Ottoman embroidery, of which they eventually became an intrinsic part. From the 18th century onwards, the European influence became pronounced. No national culture exists in isolation. This cultural heritage has borrowed from others and evolved and is there to offer fresh inspiration to all who are willing to get to know it.