Project Description

6. Sayı

Escape

DİPLOMAT – NİSAN 2005

6. Sayı

Diplomat

Nisan 2005

The Republic of Turkey celebrates an important occasion on April 23: the 85th anniversary of the opening of the Turkish Grand National Assembly, or Parliament. When the Assembly began its deliberations back in 1920, the Ottoman Empire was still in existence, and an Ottoman parliament was meeting in Istanbul. But while this Ottoman parliament, dependent on the Sultan, was soon to disappear, the parliament in Ankara, based on the sovereignty of the people, was to survive and celebrate many anniversaries.

Professor Özer OZANKAYA, a regular contributor to Diplomat ever since its first edition, dwells in his Human Angle column this month on the concept of national sovereignty.

Our guests from the diplomatic and international communities, meanwhile, are Constantin GRIGORIE, the Ambassador of Romania to Ankara, and Marielle Sander LINDSTRÖM, Chief of Mission of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). Ambassador GRIGORIE speaks of the position of his country, which is now on the verge of European Union membership, and emphasises the importance which Romania places on relations with Turkey. IOM Mission Chief LINDSTRÖM informs our readers about the activities of her organisation – activities which are not often publicised as one hot news story follows another, but the importance of which for humanity are difficult to underestimate.

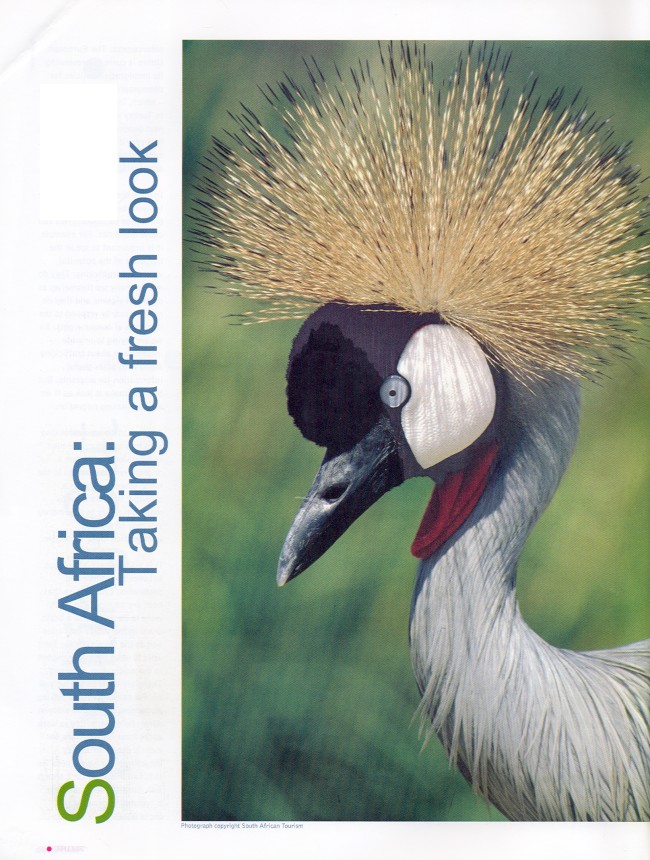

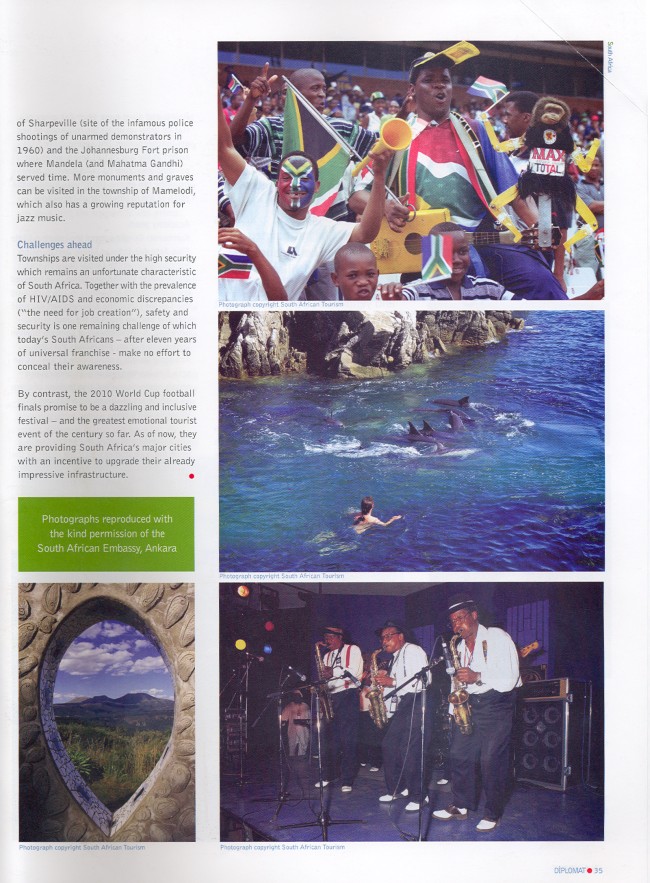

This issue of Diplomat also takes us to South Africa. It is a striking country where modern cities and fascinating natural resources go hand in hand – a country which has something for every tourist no matter how unconventional or narrow his or her field of interest may be. We are grateful to the Embassy of South Africa in Ankara for its assistance in making materials available for use in compiling this report.

For those with northern hemisphere summer holidays on their minds, we also travel to an alternative Turkish Mediterranean tourism destination, introducing readers to some of the attractive and curious places that can be visited along the coast of the province of Mersin.

Our arts pages feature another Ankara artist, Hatice Kumbaracı Gürsöz. Kumbaracı Gürsöz is no stranger to the world of diplomats. Married to a Turkish ambassador, she has opened exhibitions in every country to which she and her husband have been posted. She is now living and working as energetically as ever in the Turkish capital.

Happiness smells of chocolate, they say, and one of the best places to find it in Ankara is Patiswiss. More details can be found in the following. Gourmets, meanwhile, may enjoy our feature on Budakaltı Restaurant.

Bon appetit!

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Interview

Ambassador Grigorie: A Special Partnership

by Bernard KENNEDY

Ambassador Constantin Grigorie of Romania came to Ankara in January 2004 on his third ambassadorial posting, having spent four years in the top job in his country’s embassies in each of Rome and Sofia. His first year in Turkey coincided with a period of intensive diplomatic exchanges and an explosion in bilateral economic ties. The ambassador has nevertheless already visited numerous provincial centres including the five largest cities and several coastal towns. In the process, he has developed a close appreciation of Turkish cuisine – recalling “exceptional kebabs” in Bursa and Adana but noting that “also in Ankara you can have a very good kebab”. In the following interview, he talks to Bernard Kennedy about Romania’s relations with Turkey, about the challenges of EU accession and, just briefly, about football.

Q How would you sum up relations between Turkey and Romania?

A Turkey is a very very important partner for Romania. There is a special bilateral partnership. There was a very intensive high-level political dialogue between the two countries last year. President Ion Iliescu and Prime Minister Adrian Nastase both visited Turkey, as did the speaker of the Romanian Senate Nicolae Vacaroiu. Meanwhile, both President Ahmet Necdet Sezer and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey paid visits to Romania. More than half of the ministers making up the governments of each of the two countries also took part in mutual bilateral visits. The dialogue will continue with the same intensity in 2005. Romanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mihai-Razvan Ungureanu came to Ankara in late March, and a visit from Calin Popescu Tariceanu, the new Prime Minister, is envisaged for the spring months. Romania’s new president, Traian Basescu, will be travelling to Turkey later in the year, while Bülent Arınç, speaker of the National Assembly of Turkey, will make the journey to Bucharest. Once again, more than half of the ministers in the two governments will be exchanging bilateral visits.

Q What about economic ties?

A The volume of trade between Turkey and Romania reached over US$3bn in 2004 compared to US$1.8bn in the previous year. As a result, Turkey overtook Russia and the United Kingdom to become Romania’s fourth largest economic partner after Italy, Germany and France. There are about 10,000 joint ventures involving Turkish capital in Romania, and the level of Turkish investment has reached some US$800m. Turkish companies have participated in the Romanian privatisation programme, and companies like Arçelik and Kombassan have become well-known names – to give just two examples. At the same time, we are discussing very important investment projects, particularly in the field of energy. This subject was touched on again during the visit of Foreign Minister Ungureanu. We have started to elaborate a feasibility study on the transport of electricity via a 600MW submarine cable stretching from Turkey to Constanza.

Q Are there also cultural links between the two countries?

A Prime Minister Erdoğan’s official visit to Romania last year greatly enhanced the cultural dimension of relations between the two countries. During the course of the visit, the Turkish Prime Minister presented a replica of the sword of the Moldavian prince Stephen the Great. And on the occasion of the visit of President Sezer to Romania, the original of the sword, which forms part of the collection of the Topkapı Museum, Istanbul – was presented to the Romanians for a period of three weeks. These gestures took place as we commemorated the 500th year of the death of Prince Stephen the Great in 2004. Meanwhile, with the support of the local authorities, a square in Istanbul was named after another important Romanian prince, Dimitri Cantemir, who lived in the city in the 18th century, and who is also well known for his academic works. Prince Cantemir’s house in the Fener district is now being restored and will be transformed into a museum at the beginning of next year.

Last but not least, the Romanian Orthodox community in Istanbul acquired a church from the Greek Orthodox Community last year, and we are very grateful to the Turkish government for approving this arrangement. We also look very favourably on the request for a new Turkish mosque to be built in Bucharest, larger than the existing one, and we look forward to receiving a piece of land for the construction of a Romanian Orthodox church in Istanbul.

As an expression of the attention which we are paying to bilateral relations, we last year opened a General Consulate in Izmir and a cultural center in Istanbul. As a result, Romania, now, has more extensive official representation in Turkey than in any other country in Europe apart from France and Germany.

Q To what do you attribute the close relations between Turkey and Romania?

A First, there is a tradition of good relations between the two peoples and countries. Secondly, we are quite close to one another geographically. There is also a Turkish minority community of around 30,000 people in Romania who are respected and loved, and who have two representatives in the Romanian parliament. The existing conditions for the development of business ties between the two countries have also played an important role. Most of the 10,000 investments, which I mentioned earlier, are due to the initiative displayed by Turkish businessmen in response to the favourable business climate in Romania.

There is another force uniting Turkey and Romania which perhaps I should mention – namely, football. The Romanian football players, Hagi and Popescu, and the coach Lucescu are very well known in Turkey. Their careers here have also helped to make Turkey popular in Romania. During the closıng stages of the World Cup in 2002, when Turkey came third, all the Romanians were supporting the Turkish national side. Actually, this is not a new phenomenon. During a discussion with Prime Minister Erdoğan some months ago, I was very impressed to hear him mention the names of Nunweiler and Datcu, two Romanians who played for Fenerbahçe thirty years ago.

Q Turkey and Romania are also active in the same international organisations…

A Yes. Romania is very grateful for the support lent by Turkey during its bid for NATO membership, and it was by a happy coincidence that the first NATO summit in which Romania participated as a member took place in Istanbul. In turn, we are ready to extend political support to Turkey in its EU membership process and to share our experience in the area of EU accession. Turkey and Romania are also both members of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) initiative, which aims to increase the cooperation among all states in the region in order to build peace, stability and prosperity in the region. We face challenges in the areas of security and organised crime. I think we also have to increase the role of the BSEC in the economic sphere, with special reference to the energy sector. This was a major reason for the visit of Foreign Minister Ungureanu. In addition, Romania is currently in the chair of the SouthEast Europe Cooperation Process (SEECP). Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül is expected to attend the ministerial meeting of the SEECP which will take place in Bucharest on May 10, and we hope that President Sezer will attend the summit meeting due to take place on May 11.

Q Would it be true to say that Romania is following a more active foreign policy now that its economic problems are receding?

A For the past four years the Romanian economy has grown by between 5% and 8% each year. Meanwhile inflation has been reduced to single figures. Things are moving in Romania, and the EU and the United States have recognised that the country has a working market economy. But I think our foreign policy is really a separate issue. It is a duty and responsibility, which befalls us as a future member of the European Union and as a NATO member.

Q What is the current state of play in Romania’s EU accession process?

A According to the calendar, there will be a debate and a vote in the European Parliament on the Accession Treaty on April 13. Romania and Bulgaria will then sign an Accession Treaty with the EU on April 25. This will be followed by a process of ratification by all the national parliaments of the EU member countries, and 2007 will be the year when Romania and Bulgaria become full members. More than 80% of the population of Romania is in favour of accession to the EU, although they appreciate very well that it will involve sacrifices as well as benefits. Even after accession it will be some years before the process is complete. It is not possible to assimilate the entire 80,000-page acquis communautaire at the moment of accession, and so various transition periods have been agreed during the course of the negotiations.

Q Turks appear more doubtful about the benefits of EU accession. What would you say to them?

A It’s not a question of anything being imposed on Turkey. We and the Bulgarians faced the same problems as Turkey does now. We had to understand the need to harmonise our interests with those of the whole European community. The size of the country is a very important variable. I remember when Spain and Portugal joined, the two countries became members simultaneously, but Portugal concluded negotiations fifteen months before Spain, because if you are a bigger country it takes more time. Even for Romania and Bulgaria – and we are not the biggest countries – it will be almost ten years since negotiations began. Turkey signed an association agreement in 1963 and already has a customs union with the EU. Under the communist regime we too had more agreements with the EU than the other communist countries. But the transposition of the acquis is a much greater issue and it will take time. We have to respect the rules of the game. We the newcomers have to adapt ourselves to these realities.

I must say that I am very optimistic about Turkey’s perspective and I am sure that the EU needs Turkey in its ranks. I have a great respect for the history of Turkey. 1453 was a very important moment in history, when Turkey entered Europe. Today, 500 years later, I am sure that process will be finalised by the process of accession to the EU.

Q How do you find living in Turkey and more particularly in Ankara?

A I enjoy living in Turkey very much. I feel at home here. It is a country with a brilliant history, a great present and I am sure an exceptional future. Turkey is more than a country; it is a continent. Last month I was in Adana and it was 22 degrees Celsius, and then in the same week I went to Kars and it was minus 25. But Turkey’s most important treasure is neither its history nor its geography but rather its people. I am greatly impressed by their sincerity and hospitality.

I am doing my best to get to know Turkey better. For a start, the Turkish cuisine is very healthy and very close to the Romanian cuisine. To make food is also an art, and there are similarities with Mediterranean cooking, which I also experienced in Italy, a country well known for its art. But at the same time you can appreciate quite different food from the many different regions.

I see no difference between Ankara and all other important European capitals. It is a large civilised city and has a particularly good climate. The diplomatic community is very friendly and enjoys excellent relations with the Turkish Foreign Ministry.

Human Angle

The importance of National Sovereignty

by Prof. Dr. Özer Ozankaya

The Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA) celebrates the 85th anniversary of its foundation this month. It was this Assembly which brought victory in the Turkish War of Independence and achieved the revolutions of Turkish democracy under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal. All of this was due to the principle that “Sovereignty belongs unconditionally to the nation.”

In line with this principle, a social order based on freedom, national independence and peace was established. Today, however, the modern science and technology which is transforming our world into a “global village” has been placed in the service of the “Political West” rather than in the service of national sovereignty, and the benefits of national sovereignty in terms of independence, freedom, peace and social justice are under attack.

During this month’s celebrations, the Turkish Grand National Assembly needs to assert first and foremost the principle of national sovereignty which is the base of its legitimate existence, and not allow this principle to be distorted or emptied.

A national movement

The glorifying of Mustafa Kemal to the rank of “Atatürk” – as well as the international accolades accorded to him – are also closely related to his commitment to the true meaning and honest implementation of the principle of “national sovereignty”. The author of the words, “Freedom and independence is my character” had an early record of resisting oppression, supporting a constitutional order and separating military and political power. With the War of Independence his commitment to the national sovereignty became explicit.

In the Amasya Declaration, the first declaration he made to the nation and to the world, he said, “The future of the nation will be determined again by the decision of the nation. Whatever the decision of the nation, it will appear at the General Congress to be assembled in Sivas”. The War of Independence began at the congresses and was executed by the TGNA. And it was this strategy that made victory possible at Sakarya:

“War means two nations confronting and fighting with each other with their entire beings, with all their material and spiritual powers. Because of this I had to involve the Turkish nation in the war as much as the army at the front… Not only those facing the enemy but everyone – in his village, at home, in the field – would regard himself as being on duty … and give his entire being to the war. Nations which are slow to give their entire material and spiritual existence to the defence of the country cannot be considered really to have accepted the risk of war and conflict. However this is the only condition for the success of wars of independence.”

Consolidating victory

While accepting the duty of commander-in-chief conferred on him by the TGNA, Atatürk continued to insist that the war was the war of the nation. He insisted that his authority be limited to three months. He was to attribute the victory which he achieved to the power of “a thought accepted completely by a nation.”

After the victory, the next stage was the institutionalisation of the principle of national sovereignty, guaranteeing that the nation would never have to be “freed” again – in other words, that the administration will always be determined with the free vote of the nation. This process included the abolition of the sultanate and caliphate and of organisations of oppression such as sects and lodges, the secularisation of political and public life, the establishment of a secular and general order of education, the achievement of equality between men and women, the prohibition of titles, signs and forms of dress that confer social and political privilege in the public sphere (hat and clothing revolution) and the adoption of the national language as the language of law, administration, education and science (language and writing revolutions). All these reforms were indispensable conditions of the principle of national sovereignty. All were approved by the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

Dictratorship of the majority?

Those whose traditional interests were threatened by these developments suggested that the Turkish people could not be governed without caliphate-sultanate. They even attempted to offer the position of sultan and caliph to Mustafa Kemal himself. As soon as they understood that this was not possible, they resorted to the deception (demagogy) that they were the ones upholding the will of the people. They assumed that the people, who had not yet acquired the culture of being free and equal citizens, would mostly vote for the rule of a caliphate-sultanate. But Mustafa Kemal again highlighted that the principle of “national sovereignty” does not mean random majority order.

It is a point which many democratic countries have come to realise and inscribe in their constitutions only after experiencing disasters of fascism, communism, religious oppression and two world wars.

In 1924, Mustafa Kemal asked all the army commanders including Chief of General Staff Marshal Fevzi Çakmak who also held parliamentary seats to relinquish them. Most withdrew, and what Atatürk termed a “conspiracy against the Republic” failed. Thus Mustafa Kemal established the necessary separation of the military from the political power struggle.

Subsequent anti-democratic movements such as the Izmir assassination attempt, the Şeyh Sait Revolt and the Menemen incident failed. These were supported by the “Political West”, which shows the importance of the principle of national sovereignty for both developing countries and for the West itself.

The balance sheet

Thanks to the principle of national sovereignty:

1) The concept of the Turkish nation had come to embrace all individuals tied to the Turkish Republic through citizenship. All were equipped with equal individual and citizenship rights without any distinction of race, gender, religion, sect or occupation. Thanks to this definition of the democratic Turkish nation, domestic and foreign imperialistic attempts to pave the way for ethnic conflicts in Turkey have failed.

2) The notion of the Turkish homeland was clarified and all kinds of expansionist and irredentist aims were excluded. Accordingly, war came to be seen as murder unless the life of the nation is in danger. The principle of “Peace at home peace in the world” was accepted. Turkish foreign policy came to be determined freely and in Ankara for the sake of legitimate national interests. The adaption of foreign policy to the aims of other states was over. The Turkish Republic obtained a respected and active place in the world of international relations.

3) Laicism achieved its clear and true definition: The authority to make laws to regularise relations between people was vested solely in the TGNA. Laws could not be introduced on behalf of religion. Every adult was free to choose his religion.

4) The human and citizenship rights and freedoms of women, who make up 50% of the public, were recognised and their free and effective participation in social life assured.

5) The ideas of freedom, independence and scientific thinking were induced in young people through the unification of education. Thus the principle that “Morality formed on intimidation, is neither a wise nor a reliable morality” was put into practice.

6) The economic system was based on permitting public enterprise for the purpose of assuring the production of goods and services in the public interest, preventing monopolisation and ensuring fair rewards for labour, while ensuring that private enterprise become the main source of economic activities.

7) The survival of the arts, philosophy, science and national language was ensured by making the legal, administrative and scientific language identical with the daily language of the public.

These were also the necessary requirements and the true assurances of political, military, judicial, educational, economic and cultural independence, referred to by Atatürk as “absolute independence”. The same principles are essential if modern science and technology is to be used with the aim of meeting the requirements of all nations for freedom, peace and welfare in the realm of international relations.

World view

1915: Was it a genocide?

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV

Sections of the Armenian diaspora are preparing to commemorate the events of 1915 in war-time Anatolia with additional zeal on 24 April 2005, to mark their 90th year. The assertion of these groups has always been that there was a genocide – a state plan or operation to exterminate a people. The objective reply, based on reliable and pertinent documentation should be: There was no genocide committed against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire before, during or after the First World War.

This general statement does not mean that nothing happened in 1915. Many things did occur – among them Armenian armed revolt, cooperation between Armenians and the invading Russians, attacks on defenseless Muslim villages, towns and quarters, the participation of the Armenians in about a dozen wars, the Ottoman decision to relocate them, the safe arrival of the overwhelming majority at their destinations, assaults on some Armenian groups by Muslim civilians seeking booty or revenge, casualties among all citizens because of the adverse war conditions and the spread of contagious diseases, and the Ottoman decision, taken within less than a year, to halt the relocation and ask the Armenians to come back.

Ottoman tolerance

The allegation that the Ottoman Turks misruled the non-Muslim citizens of their state is a gross denial of historical facts. “Tolerance” should be the first word used in describing the six centuries of Ottoman policy towards the minorities of the Empire. Thanks to the “millet” system, a cornerstone of Muslim law, all of these minorities – among them the Greeks, other Orthodox peoples like the Bulgarians and the Serbs, the Gregorian Armenians, the Sephardic Jews who had escaped from Europe and found a haven among the Turks, Catholics like the Croats, Levantines and some Lebanese, and the Protestants – were left to govern themselves, use their own languages, worship in their own way, maintain their cultures, preserve their traditions, and run their schools and courts.

The Turks opened their doors to the persecuted Jews, the Russian Old Believers and to Polish and other refugees fleeing after the 1848 Revolution. This practice was remarkably “modern” considering that during the same period in Europe Catholics were ill-treated by Cromwell’s soldiers, the Huguenots were slaughtered by the French and Calvinists were oppressed variously. While Europe and North America sent missionaries all over the world to convert others to Christianity, the Ottomans had guaranteed religious freedom to all subject peoples. This is also what the Arabs had done during their long stay in Spain. Had the Ottomans converted their subjects to Islam by force, there would have been a band of Turkish-speaking Muslims from the Adriatic to Basra

As long ago as 1461, the Turks had been the first to recognize independently the Gregorian Armenian Church, disowned by other Christians for its Monophysite beliefs ever since the Calcedon Council’s decision of the year 451. The Ottoman Empire had 29 Armenian civilian generals, 22 Cabinet members, 23 parliamentarians, seven ambassadors, 11 consuls, 11 university teachers, and hundreds of other Armenians in various posts. Far from being discriminated against, they enjoyed a favored status relative to their weight in the population. In 1913, even the Ottoman Foreign Minister was an Armenian – Gabriel Nouradoungian.

Armenian revolt

The Armenian subjects suffered not from Ottoman rule, but at times from the misrule of their own leaders. At the time when they understandably focused their criticisms on the central government, beginning with the end of the 19th century, Muslim intellectuals were also seeking change, But with the rise of nationalism in the Balkans and elsewhere, the goal of reforms and modernization for all was overshadowed, and minorities came to exploit their autonomy, eventually demanding territories much more extensive than they had ever ruled at any single moment of time.

In Eastern Anatolia, which the Armenian diaspora frequently opts to call “Armenia”, the Armenians, whose original homeland was in the Caucasus, were everywhere a small minority. They had been dispersed by Byzantine rule before the Turks appeared on the scene one-thousand years ago. The Turks acquired territory in the region not from Armenians but from the declining Byzantine Empire. For more than 900 years, their relations with the Turks were friendly, peaceful, even brotherly.

Much later, like the non-Muslim Balkan peoples, Armenians hoped and endeavored to kill or drive out the Turks and other Muslims so as to pave the way for a territorial claim. Their so-called political parties, the Hunchaks and the Dashnaks – “terrorist” organizations by today’s standards – resorted to large-scale propaganda and bloodshed from the late 19th century onwards in the hope of stimulating strife between the two communities and obliging the Europeans to intervene militarily. They hurled bombs, assassinated officials, attacked public places and villages and caused much destruction and bloodshed. All of this has been recorded in the archives of many governments and the reports of many foreign observers. As Armenian writers (like L. Nalbantian) confess, “the most opportune time was to institute the general rebellion…when Turkey was engaged in war.”

When war came, the Armenian residents of Van attacked the Muslim quarters of the area, welcomed the invading Czarist Russian armies and declared their own independent state. Their heavily armed fighting force consisted of close to 160.000 soldiers, according to the admissions of a number of Armenian sources. Many Armenian commanders later published memoirs admitting their belligerency, and a host of Armenian and foreign sources refer to them as “combatants”. Their barbarity at times reached such proportions that some Russian officers on the Eastern Front and later some French commanders in the Adana region on the Southern Front tried to withdraw them to the rear lines.

Wars and relocation

Armenian battalions participated in about a dozen conventional wars, civil wars and similar serious armed encounters between 1914 and 1922: guerilla warfare against the Ottoman army and the Muslim villages and towns; acts carried out in cooperation with the regular Russian forces; overpowering the civilians of the Eastern region after the Bolshevik Revolution; battles with Turkish General Kazım Karabekir’s 15th Army-Corps; encounters with the detachments of the newly-formed Ankara Government; wars with the neighbouring Georgians and the Azerbaijanis; the armed suppression of Armenia’s own Azeri minority; joint bloody military exploits with the occupying French troops in the Adana region and with the invading Greeks in the Aegean region. In all these combats, both sides, certainly including the Armenians, suffered tremendous casualties. Let us ask the militant Armenians, their associates and disinterested third parties whether its is justifiable to consider such losses as the result of a genocide.

The terribly detrimental war conditions that caused the death of many Turks and Armenians are not a matter of propaganda or an excuse for the losses suffered. In all wars fought everywhere throughout the world up to the 20th century, more men died of disease than in actual combat at the fronts. The freezing winter on the Sarıkamış slopes, for instance, caused the extinction of about 70.000 Turkish soldiers in one night. Soldiers perished on account of contagious diseases such as cholera, dysentry, typhus, typhoid and malaria, in addition to pneumonia, tuberculosis, influenza, and enteric fever. These afflictions affected all forces and civilians, whether Turkish or Armenian. No less than 1,175,000 Turkish soldiers were admitted to hospitals, and many did not survive. Even the top Turkish, German and British commanders could not be saved. Although the number of civilian Armenian casualties caused by sickness cannot be documented, their number should not be added to the column of those deliberately misconstrued to have been “massacred”.

After the revolt and the Armenian assault on the Muslims of Van, the Ottoman Government aimed to remove the Armenians and relocate them away from the war zones. Militant Armenian circles conveniently consider the “24th of April” – when 235 Armenians in Istanbul were put under custody – as the beginning of the controversy. This is an attempt to cover up the crucial episode in the crisis: the immediate motive behind the relocation order was the armed revolt in Van, which occurred earlier, and the need to maintain the security of the border.

Counting the losses

The replacement orders may be found in the rich Ottoman archives and in foreign files such as those in the Public Record Office in London (for instance, FO, 371/4241/170751), They are very clear that the voyages should not cause any killings, that they should exclude Protestant, Catholic, handicapped and orphan Armenians – as well as Armenians of certain professions – and their families, that the relocated persons should be protected and fed during the journey, and that they should be given homes and proper utensils to work in their new surroundings.

Some marauding brigands nevertheless attacked the caravans. Orders were issued that the culprits should be punished and that three local investigation committees be set up. According to Bogos Nubar, the head of the Armenian Delegation at Versailles (1918-19), 6-700.000 Armenians were transferred, 390,000 of whom reached their destinations. But according to Prof. Yusuf Halacoğlu, the director of the Turkish Historical Society, the number of the relocated people is a little less than 450,000. If 390,000 reached their destinations, then the number who went missing works out at either 260,000 (on the basis of the Bogos Nubar document) or 60,000 (in the Halacoğlu estimate). One cannot be certain how many of the losses were due to recurrent arms, diseases, war conditions or the attacks of brigands. Although the British had to free the 144 Ottoman leaders imprisoned in Malta, it was the Turkish courts that put 1,397 persons on trial, resulting in many guilty verdicts and some executions.

The Armenian losses were much lower than the figures of 3.5 million, 2 million, 1 million or just under a million variously put forward by militant Armenians. The total population of the Armenians in the whole of the Ottoman Empire was barely 1.3 million. The Ottomans counted their peoples in accordance with modern methods under the direction of the statistics bureau, which was headed successively by a Jew, an Armenian and an American.

Inventing the myth

Then how did such terribly invented figures and falsehoods emerge? It was the duty of Masterman’s propaganda bureau at Wellington House to disseminate such information. Ambassador H. Morgenthau’s book, written collectively for war purposes, and the works of missionaries like Dr. J. Lepsius presented entirely one-sided stories. In addition, a number of Armenians printed forged “documents”, even presenting the picture of an old (1871) oil painting as a photograph of Armenian skulls. Novels like Forty Days of Musa Dagh and movies like Ararat captured the Western imagination. Many “learn” from such biased sources rather than study first-hand archive material. Now, “1915” has become a part of the Armenian identity, transferred from generation to generation, with little connection to what actually happened in history.

Arts:

The world of Hatice Kumbaracı-Gürsöz

by Sibel DORSAN

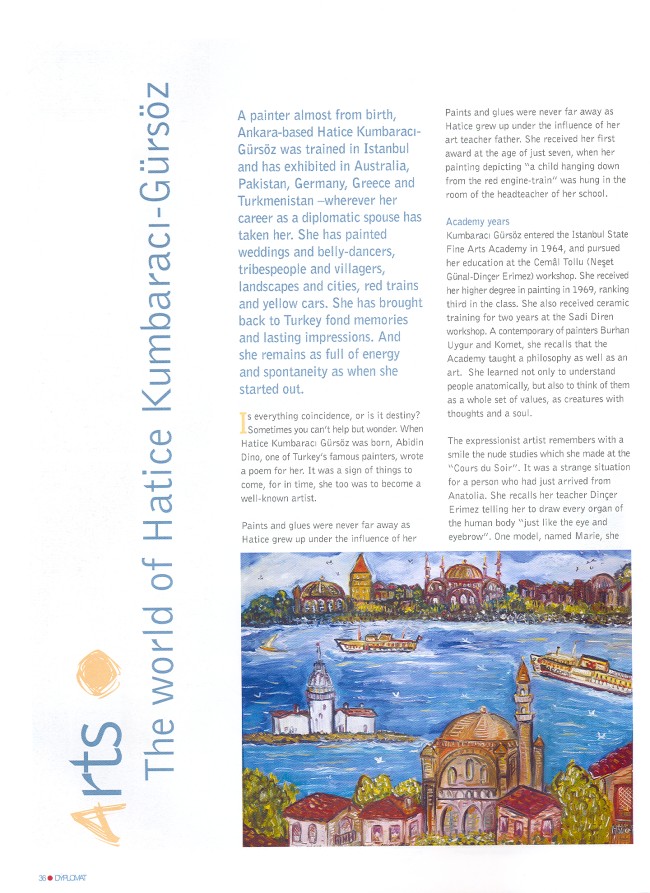

A painter almost from birth, Ankara-based Hatice Kumbaracı-Gürsöz was trained in Istanbul and has exhibited in Australia, Pakistan, Germany, Greece and Turkmenistan –wherever her career as a diplomatic spouse has taken her. She has painted weddings and belly-dancers, tribespeople and villagers, landscapes and cities, red trains and yellow cars. She has brought back to Turkey fond memories and lasting impressions. And she remains as full of energy and spontaneity as when she started out.

Is everything coincidence, or is it destiny? Sometimes you can’t help but wonder. When Hatice Kumbaracı Gürsöz was born, Abidin Dino, one of Turkey’s famous painters, wrote a poem for her. It was a sign of things to come, for in time, she too was to become a well-known artist.

Paints and glues were never far away as Hatice grew up under the influence of her art teacher father. She received her first award at the age of just seven, when her painting depicting “a child hanging down from the red engine-train” was hung in the room of the headteacher of her school.

Academy years

Kumbaracı Gürsöz entered the Istanbul State Fine Arts Academy in 1964, and pursued her education at the Cemâl Tollu (Neşet Günal-Dinçer Erimez) workshop. She received her higher degree in painting in 1969, ranking third in the class. She also received ceramic training for two years at the Sadi Diren workshop. A contemporary of painters Burhan Uygur and Komet, she recalls that the Academy taught a philosophy as well as an art. She learned not only to understand people anatomically, but also to think of them as a whole set of values, as creatures with thoughts and a soul.

The expressionist artist remembers with a smile the nude studies which she made at the “Cours du Soir”. It was a strange situation for a person who had just arrived from Anatolia. She recalls her teacher Dinçer Erimez telling her to draw every organ of the human body “just like the eye and eyebrow”. One model, named Marie, she recalls, held a long, thick stick in her hand, which she used to warn male students to concentrate. Another unforgettable memory is the competitions that were staged for paintings on any theme created to the accompaniment of classical music. “Wherever the music takes you, that’s what you paint,” she says, and she frequently won prizes.

From Taksim to Melbourne

Colour is the key element in Kumbaracı-Gürsöz’s early paintings. Perspective and light are created with colour. In the darkish colours, there are similarities with George Roueau and especially with Emil Nolde, while the simple figures remind one of Chagall. In time, the colours become lighter and a style emerges which reflects the beauty of pure thoughts and innocent, naïve feelings. “Painting is a process which never ends and further develops and changes,” she says. The process was to continue after her marriage to a diplomat, which caused her to live in many different places and gave her the opportunity to learn of different cultures and to visit innumerable museums, galleries and exhibitions.

First came Australia, the cradle of modern art. She was especially impressed by the primitive paintings of the Aboriginals. The effect was soon to become apparent in her portrait paintings and colours. She met Pierre Poirier, who liked her paintings and became her manager. As a result, Kumbaracı-Gürsöz – whose first personal exhibition had taken place at the Taksım Art Gallery in Istanbul – opened her second at the Bartoni International Gallery in Melbourne. Her paintings were praised in the local newspapers, and most of them were sold.

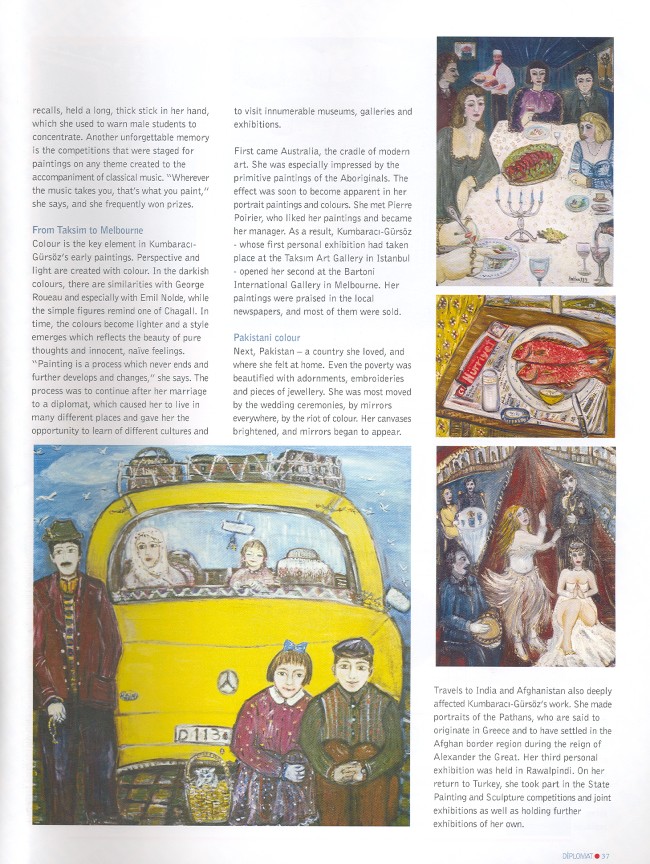

Pakistani colour

Next, Pakistan – a country she loved, and where she felt at home. Even the poverty was beautified with adornments, embroideries and pieces of jewellery. She was most moved by the wedding ceremonies, by mirrors everywhere, by the riot of colour. Her canvases brightened, and mirrors began to appear. Travels to India and Afghanistan also deeply affected Kumbaracı-Gürsöz’s work. She made portraits of the Pathans, who are said to originate in Greece and to have settled in the Afghan border region during the reign of Alexander the Great. Her third personal exhibition was held in Rawalpindi. On her return to Turkey, she took part in the State Painting and Sculpture competitions and joint exhibitions as well as holding further exhibitions of her own.

Kumbaracı-Gürsöz and her husband moved to Nurnberg when her second child was still very young, and she was content to take part in joint exhibitions. In Bonn, however, she also held five exhibitions of her own. She became a member of the German Federal Artists Union (BBK). Pessimistic in Australia and colourful in Pakistan, the paintings of her German period are more disciplined and focus mainly on nature.

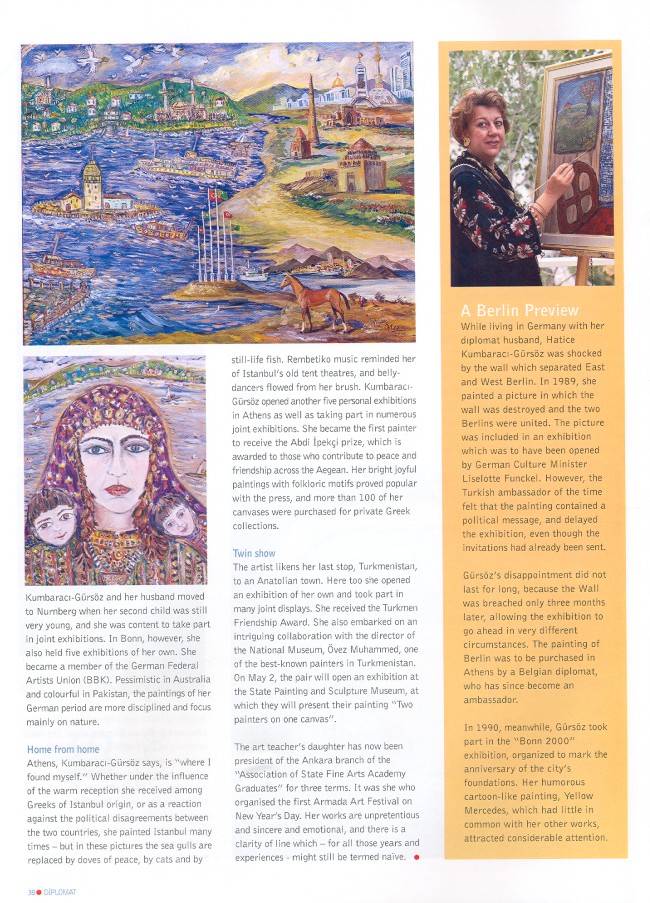

Home from home

Athens, Kumbaracı-Gürsöz says, is “where I found myself.” She became deeply aware of the similarities between Turks and Greeks in every field of life. She made many friends in artistic circles. Whether under the influence of the warm reception she received among Greeks of Istanbul origin, or as a reaction against the political disagreements between the two countries, she painted Istanbul many times – but in these pictures the sea gulls are replaced by doves of peace, by cats and by still-life fish. Rembetiko music reminded her of Istanbul’s old tent theatres, and belly-dancers flowed from her brush.

Kumbaracı-Gürsöz opened another five personal exhibitions in Athens as well as taking part in numerous joint exhibitions. She became the first painter to receive the Abdi İpekçi prize, which is awarded to those who contribute to peace and friendship across the Aegean. Her bright joyful paintings with folkloric motifs proved popular with the press, and more than 100 of her canvases were purchased for private Greek collections.

Twin show

The artist likens her last stop, Turkmenistan, to an Anatolian town. Here too she opened an exhibition of her own and took part in many joint displays. She received the Turkmen Friendship Award. She also embarked on an intriguing collaboration with the director of the National Museum, Övez Muhammed, one of the best-known painters in Turkmenistan. On May 2, the pair will open an exhibition at the State Painting and Sculpture Museum, at which they will present their painting “Two painters on one canvas”.

The art teacher’s daughter has now been president of the Ankara branch of the “Association of State Fine Arts Academy Graduates” for three terms. It was she who organised the first Armada Art Festival on New Year’s Day. She is also busy painting. Anatolian people, especially women, are currently her favourite themes. Her poetic narration draws on fairy tales and myths, and her careful composition from Turkish miniature art. Her works are unpretentious and sincere and emotional, and there is a clarity of line which – for all those years and experiences – might still be termed naïve.

A Berlin Preview

While living in Germany with her dıplomat husband, Hatice Kumbaracı-Gürsöz was shocked by the wall which separated East and West Berlin. In 1989, she painted a picture in which the wall was destroyed and the two Berlins were united. The picture was included in an exhibition which was to have been opened by German Culture Minister Liselotte Funckel. However, the Turkish ambassador of the time felt that the painting contained a political message, and delayed the exhibition, even though the invitations had already been sent.

Gürsöz’s disappointment did not last for long, because the Wall was breached only three months later, allowing the exhibition to go ahead in very different circumstances. The painting of Berlin was to be purchased in Athens by a Belgian diplomat, who has since become an ambassador.

In 1990, meanwhile, Gürsöz took part in the “Bonn 2000” exhibition, organized to mark the anniversary of the city’s foundations. Her humorous cartoon-like painting, Yellow Mercedes, which had little in common with her other works, attracted considerable attention.

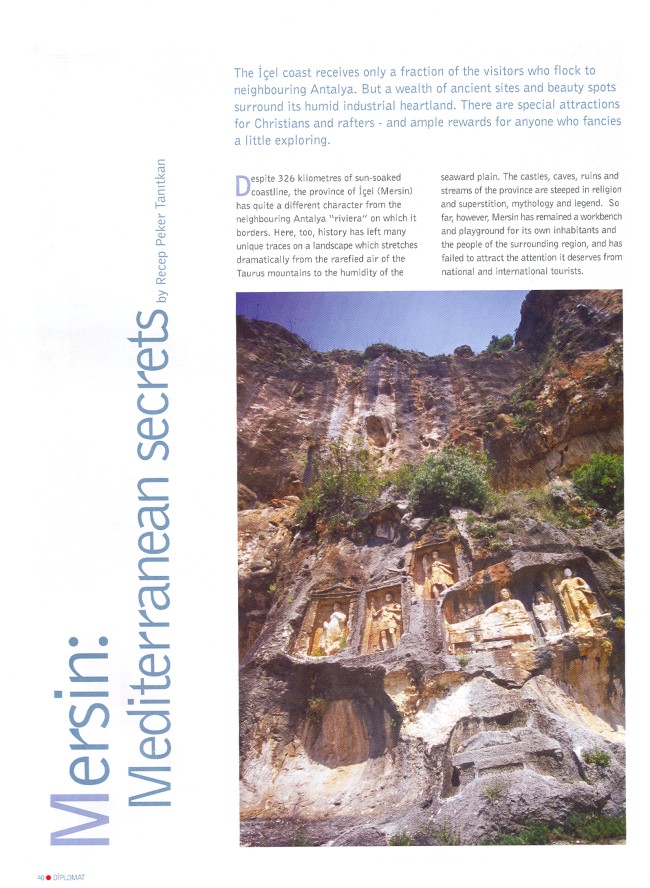

Mersin: Mediterranean secrets

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

The İçel coast receives only a fraction of the visitors who flock to neighbouring Antalya. But a wealth of ancient sites and beauty spots surround its humid industrial heartland. There are special attractions for Christians and rafters – and ample rewards for anyone who fancies a little exploring.

Despite 326 kilometres of sun-soaked coastline, the province of İçel (Mersin) has quite a different character from the neighbouring Antalya “riviera” on which it borders. Here, too, history has left many unique traces on a landscape which stretches dramatically from the rarefied air of the Taurus mountains to the humidity of the seaward plain. The castles, caves, ruins and streams of the province are steeped in religion and superstition, mythology and legend. So far, however, Mersin has remained a workbench and playground for its own inhabitants and the people of the surrounding region, and has failed to attract the attention it deserves from national and international tourists.

Town and country

Little more than a fishing village until 150 years ago, Mersin city has grown into an international port with a population of over half a million. If business is brisk in Mersin port, the adage runs, then all is well in Turkey. Together with adjoining Tarsus – itself home to over 200,000 inhabitants – Mersin makes up a major industrial conurbation comparing favourably in many ways with nearby Adana and with the rival port of Iskenderun, which it faces across the northeast corner of the Mediterranean.

Agriculture too is intensive, with greenhouse fruit and vegetable farms and irrigated plains that produce – inter alia – the bulk of Turkey’s citrus crop. Perhaps it is all this economic activity as much as the distance from major cities in western Turkey and Europe which has kept coastal towns like Silifke, Erdemli and Anamur of delta, castle and banana fame away from the beaten track, and confined picturesque Mut and rugged Gülnar to the logbooks of hardened travellers.

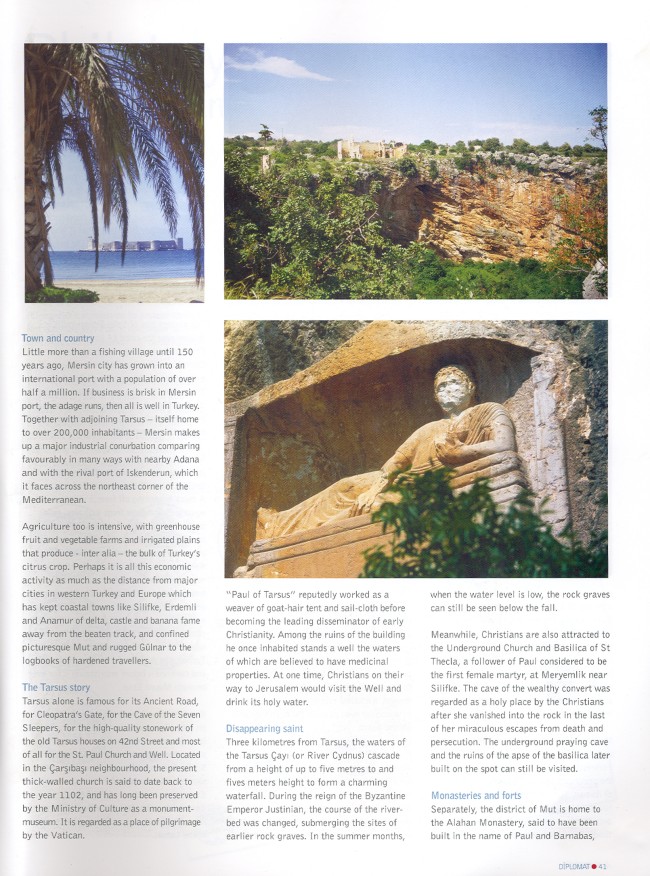

The Tarsus story

Tarsus alone is famous for its Ancient Road, for Cleopatra’s Gate, for the Cave of the Seven Sleepers, for the high-quality stonework of the old Tarsus houses on 42nd Street and most of all for the St. Paul Church and Well. Located in the Çarşıbaşı neighbourhood, the present thick-walled church is said to date back to the year 1102, and has long been preserved by the Ministry of Culture as a monument-museum. It is regarded as a place of pilgrimage by the Vatican.

“Paul of Tarsus” reputedly worked as a weaver of goat-hair tent and sail-cloth before becoming the leading disseminator of early Christianity. Among the ruins of the building he once inhabited stands a well the waters of which are believed to have medicinal properties. At one time, Christians on their way to Jerusalem would visit the Well and drink its holy water.

Disappearing saint

Three kilometres from Tarsus, the waters of the Tarsus Çayı (or River Cydnus) cascade from a height of up to five metres to and fives meters height to form a charming waterfall. During the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, the course of the river-bed was changed, submerging the sites of earlier rock graves. In the summer months, when the water level is low, the rock graves can still be seen below the fall.

Meanwhile, Christians are also attracted to the Underground Church and Basilica of St Thecla, a follower of Paul considered to be the first female martyr, at Meryemlik near Silifke. The cave of the wealthy convert was regarded as a holy place by the Christians after she vanished into the rock in the last of her miraculous escapes from death and persecution. The underground praying cave and the ruins of the apse of the basilica later built on the spot can still be visited.

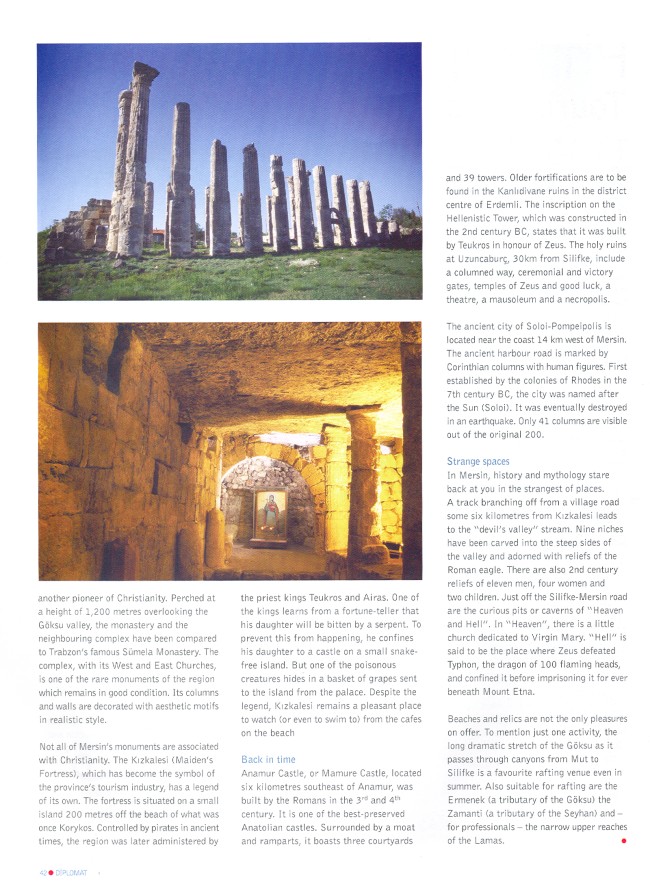

Monasteries and forts

Separately, the district of Mut is home to the Alahan Monastery, said to have been built in the name of Paul and Barnabas, another pioneer of Christianity. Perched at a height of 1,200 metres overlooking the Göksu valley, the monastery and the neighbouring complex have been compared to Trabzon’s famous Sümela Monastery. The complex, with its West and East Churches, is one of the rare monuments of the region which remains in good condition. Its columns and walls are decorated with aesthetic motifs in realistic style.

Not all of Mersin’s monuments are associated with Christianity. The Kızkalesi (Maiden’s Fortress), which has become the symbol of the province’s tourism industry, has a legend of its own. The fortress is situated on a small island 200 metres off the beach of what was once Korykos. Controlled by pirates in ancient times, the region was later administered by the priest kings Teukros and Airas. One of the kings learns from a fortune-teller that his daughter will be bitten by a serpent. To prevent this from happening, he confines his daughter to a castle on a small snake-free island. But one of the poisonous creatures hides in a basket of grapes sent to the island from the palace. Despite the legend, Kızkalesi remains a pleasant place to watch (or even to swim to) from the cafes on the beach

Back in time

Anamur Castle, or Mamure Castle, located six kilometres southeast of Anamur, was built by the Romans in the 3rd and 4th century. It is one of the best-preserved Anatolian castles. Surrounded by a moat and ramparts, it boasts three courtyards and 39 towers. Older fortifications are to be found in the Kanlıdivane ruins in the district centre of Erdemli. The inscription on the Hellenistic Tower, which was constructed in the 2nd century BC, states that it was built by Teukros in honour of Zeus. The holy ruins at Uzuncaburç, 30km from Silifke, include a columned way, ceremonial and victory gates, temples of Zeus and good luck, a theatre, a mausoleum and a necropolis.

The ancient city of Soloi-Pompeipolis is located near the coast 14 km west of Mersin. The ancient harbour road is marked by Corinthian columns with human figures. First established by the colonies of Rhodes in the 7th century BC, the city was named after the Sun (Soloi). It was eventually destroyed in an earthquake. Only 41 columns are visible out of the original 200.

Strange spaces

In Mersin, history and mythology stare back at you in the strangest of places. A track branching off from a village road some six kilometres from Kızkalesi leads to the “devil’s valley” stream. Nine niches have been carved into the steep sides of the valley and adorned with reliefs of the Roman eagle. There are also 2nd century reliefs of eleven men, four women and two children. Just off the Silifke-Mersin road are the curious pits or caverns of “Heaven and Hell”. In “Heaven”, there is a little church dedicated to Virgin Mary. “Hell” is said to be the place where Zeus defeated Typhon, the dragon of 100 flaming heads, and confined it before imprisoning it for ever beneath Mount Etna.

Beaches and relics are not the only pleasures on offer. To mention just one activity, the long dramatic stretch of the Göksu as it passes through canyons from Mut to Silifke is a favourite rafting venue even in summer. Also suitable for rafting are the Ermenek (a tributary of the Göksu) the Zamanti (a tributary of the Seyhan) and – for professionals – the narrow upper reaches of the Lamas.

Philately

Touristic cancellations

by Kaya DORSAN

Turkey became aware of its tourism potential during the initial years of the Republic, and a Tourism Congress was held in Istanbul in July 1931. However, the advent of World War II heralded a long period of stagnation for the sector all over the world. In the 1950s, international leisure travel revived, and Turkey resumed its efforts to promote itself.

Philately played an important part in these promotion initiatives. It was only natural for Turkey to promote its historical, cultural and ethnographic richness on its postage stamps. Not satisfied with that, it also began to make use of special postmarks – i,e, cancellations.

First resorts

The first touristic cancellation was used at the end of 1955, in the post office at the Yalova Thermal Springs, and bore a picture of the station. Soon afterwards, a special postmark came into use at Uludağ in Bursa, displaying the image of the mountain. From 1957 onwards, it was common to see cancellations depicting various touristic regions. These included the resort of Şile near Istanbul, Izmir’s famous seaside township Çeşme, Lake Abant and the ancient city of Ephesus with its House of the Virgin Mary.

In the 1960s, more and more of the sites favoured by tourists came to be depicted on touristic postmarks, among them Pamukkale, Boğazkale, Göreme and Konya. Today, such cancellations are to be found on letters and postcards sent from places of interests as far apart as Doğubayazıt and the Manyas Bird Paradise, Samsun and the Sarıkamış Ski Center.

The use of postal cancellations as a means of promotion has proved so effective that some hotels have also begun to promote themselves in this way. Moreover, it is also possible to send letters and postcards with special pictorial postmarks from many museums in Turkey, particularly Topkapı Palace and the Museum of Anatolian Civilisations in Ankara.

Any collectors?

Unfortunately, the cancellations have been slow to attract the attention of philatelists. No catalogue of these postmarks has yet been published, and information about them is incomplete even at the archives of the Turkish Post Office (PTT).

The usage of some of the cancellations has been stopped, and they are not available anymore.

Given that collectors are drawn towards rare items, it would not be surprising if philatelists soon began to collect these postmarks.

Akdağ: a horse’s paradise

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

Three hundred kilometres southwest of Ankara, the mountains and forests of Afyon conceal an equine dream come true.

A carpet of spring flowers, a curtain of pine trees, the scent of thyme… Cradled in the lap of Mount Akdağ, 1,550 metres above sea level, the Kocayayla national park in the Sandıklı district of Afyon is a heaven on earth in good weather. Nearby, the Akdağ Canyon dissects the mountainside, an unspoilt gift of nature, tempting the most cautious of souls to explore, to climb, to trek, to jump or to swim.

Suddenly a sound both familiar and strange: a thunder of hooves; a wind of manes and tails. It is Akdağ’s wild horses. White, black, piebald and bay, all are descendants of yılkı horses, released by their owners when they became too old to work. Born free, they live every bit as wild as the boar and the deer which share the same natural pastures. One moment they roam loyal, noble and docile behind their leaders; the next they erupt into bitter, snorting conflict with one of a hundred rival herds.

All who make the trip to Kocayayla may glimpse these highland mares and stallions as they graze, wonder at their survival and reflect on the improvisations of time and fortune. But to approach is unwise and the animals move on swiftly. The photographer must trust to the quickness of his or her eye and the calibre of his or her telescopic lens. Then back to Afyonkarahisar, the spa town, to view the results – and to make quite sure it was not just some midsummer mirage.

Budakaltı: Guests for dinner

By Sibel DORSAN

It may have become a chain but it is still a family business. Diplomat goes behind the scenes at one of Ankara’s favourite restaurants and learns some the recipes of its success – as well as the recipe for Sezai Bey’s “külbastı”.

For all their rushing around from work to shops and shops to kitchen, they could never quite emulate the frequent dinner parties of their childhood. The solution they found was to enter the caterıng business en famille. They still rush around, of course – but now as adult managers, all together with their father. We are talking about the Derer family – better known today as the Budakaltı group. After gaining experience at Madamın Yeri and the Kavaklı Restaurant, the family opened the Budakaltı Brasserie, which they have gradually expanded into a select chain of eating houses and cafes.

Sezai’s secret

I cannot help but ask Ertuğrul Derer the story of a dish which I have previously eaten and which is familiar to all regular customers know: the Sezai Bey usulü kekikli dana külbastı. (Sezai Bey style grilled veal cutlets with thyme). It turns out that a gentleman by the name of Sezai would come to the restaurant every lunchtime and order the very same dish, together with an orange juice. The customer becomes almost part of the family, and his chosen main course becomes so closely identified with him that his name finds its way onto the menu.

Thyme, soybean sauce, tuzot (a mixture of salts and spices), black pepper and sunflower oil are mixed together and the meat is marinated for 3-4 hours. In summer, the meat is served on a bed of hünkarbeğendi (Sultan’s favorite), and in winter, a sauté is prepared of spinach or seasonal vegetables. Accompanied by baked potatoes, the dish is both delicious and pleasing to the eye.

Sezai Bey would not disapprove if you followed it with profiteroles and ice cream – an equally irreplaceable component of the desserts list.

No bosses

The group’s watchword is to provide a good service, and it is constantly seeking to improve. Mr. Derer says he works 24 hours a day. “We are a team,” he goes on. “A hundred people work in this group but nobody is the boss. All decisions about everything are taken jointly. Everyone is responsible in their own way for improving the business, from the menu to the uniforms and from the cleaning to the shopping.”

To succeed in a business in which there are no regular hours or holidays demands commitment and sacrifice. Only by working together for years with the same well-trained personnel has Budakaltı succeeded in becoming a trade-mark.

Original options

There are 50-60 dishes on Budakaltı’s menu. One way of incorporating new tastes is to travel abroad to gastronomy fairs and to adapt the new ideas to Turkish taste. Other dishes are discovered as a result of research done by cook Mehmet Ali, who has been in the job for over 15 years.

The menu is changed three times a year. The more original flavours include soups – some cold! – of carrot, marrow, aubergine, cucumber, asparagus, apple and pear. Then there is celery with orange, chicken in sesame oil sauce, schnitzel framed in shredded tel kadayıf pastry and pumpkin profiteroles.

The cheeses are mostly foreign – French or Italian – although Turkey’s Izmir tulumu and a number of cheeses with peppers and spice are also to be found on the menu. There is a rich cellar of local and foreign wines with which to accompany all this variety.

Customer choice

Burcu Omay, one of the restaurant’s partners, joins in the conversation. While they might themselves wish to make some changes in the menu, she says, it really develops according to the wishes of the customers. She stresses that they regard the customers as guests and their main duty as to satisfy them. She believes that the people of Ankara are less fickle than the folk of Istanbul, and that they will keep coming back provided quality is maintained. Salads are disinfected.

The portions are large, containing 180-200 grams of meat, chicken or fish. No wonder, the customers generally leave the restaurant well satisfied both with the food and with the service.