Project Description

8. Sayı

Harvest

DİPLOMAT – HAZİRAN 2005

8. Sayı

Diplomat

Haziran 2005

The Past few weeks have again been a lively time for Ankara’s diplomatic community. In addition to cultural activities organized by nomerous embassies, the capital has played host to a number or interesting meetings with political dimensions. Among these, the adress given by President Viktor Yuschenko of Ukraine at the Hilton in the early days of June and the Africa Day event staged jointly bye the African embassies have made a lasting impact.

The Africa Day celebrations were organized under the aegis of Ambassador Mohammed LESSIR of Tunisia, dean of the African ambassadors to Ankara. Mr Lessir is also DİPLOMAT‘s guests this month. Besides voicing some of Africa’s expectations, he speaks enthusiastically of the Information Summit which his country is due to host in November and comments on relations between Turkey and Tunisia.

These pages also include a conversations with two equally wel-known figures in the Turkish capital. Lebanese Ambassador Georges SIAM and his wife Golda. After approximately six years in Ankara, the count-down has begun for this much-liked couple. If, as expected, they return to their country shortly, they will leave many friendships and fond memories in their wake.

Meanwhile, DİPLOMAT interviews Mehmet DÜLGER, the Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of Turkish Grand National Assembly. Mr Dülger is a veteran politician who stems from a very political family. He explains the workings of the Committee in the context of Turkish foreign policy, and reveals his plans for increasing its effectiveness.

Our arts pages this month acquaint the reader with Nuri ABAÇ, a bright young man of 80 who is one of the best-known names in Turkish painting. Both Abaç’s recents works and the many cycles through which his artistic career has evovled are sure to be of interest.

For a travel destination, we have this month selected the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. With the holiday season upon us, thoughts of this small tourism country are quick to spring to mind. If you are looking to enjoy a great holiday without going very far, the beaches of Girne are at your disposal.

Don’t miss the opportunity.

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current opinion

Direct democracy?

by Bernard KENNEDY

Switzerland is a country of about 7.5 million people residing in 20 cantons and six half-cantons. Any eight cantons or 50,000 citizens have the right to insist that new laws are put to a referendum before they can take effect. Referenda are held frequently, and the most citizens visit a polling booth several times a year. On June 5, for example, the Swiss voted by a majority of about 55% in favour of subscribing to the Schengen and Dublin accords envisaging cooperation among European countries on police and judicial systems and asylum and migration issues.

The ‘No’ votes in the French and Dutch referenda on the proposed EU Constitution demonstrated some of the (alleged) imperfections of the referendum as an institution. May citizens appeared to cast their votes in accordance with their current level of general satisfaction, their attitude to the government, or their views on arguably unrelated issues. Swiss referenda do not suffer from this drawback, partly by virtue of their very regularity, and partly because of the way Swiss governments are formed. In other respects, referenda are in principle as open to debate in the Alpen environment as they are anywhere else. Issues have to be reduced to closed (Yes or No) questions, the ability of the public to understand complex legislation is necessarily limited, an electorate may change its mind rapidly over time, and the possibility of a vote to curtail democracy itself can never be ruled out.

Most countries have held national referenda (The US, India and Japan seem to be notable exceptions). Outside Switzerland, however, referenda are held rarely, on a one-off basis and only on issues of acknowledged constitutional importance. Voters have been asked to endorse or reject: independence in East Timor, the former Yugoslavia, the former Soviet Union and Qebec; devolution of power in Scotland and Wales (twice), EU membership, treaties and the euro in several European countries; NATO membership in Spain; Republicanism in Australia, apartheid in South Africa, divorce in Ireland and changes of written constitution everywhere from Russia (1993) to Burundi (2005) – with more anticipated in Kenya, Iraq and elsewhere. In some Latin American countries, referenda are also held to endorse or recall presidents. Even on issues of this kind, few countries resort to referenda easily, and governments or parliaments, confident in their legitimacy, frequently take on the responsibility themselves.

It is worth mentioning that the Swiss also regard referenda as particularly appropriate for dealing with constitutional issues. Constitutional amendments have to be submitted to a referendum as well as being approved by both houses of Parliament. A constitutional referendum may also be sparked by a people’s initiative of 100,000 signatures.

From De Gaulle to Papadopoulos

The man who became the major protagonist of the referendum in post-war Europe was an exception to all rules: Charles de Gaulle. Seizing on a moment of national crisis in 1958, he succeeded in having the French public approve a new and perceivedly more authoritarian constitution by an 85% majority. In this way he replaced the ‘Fourth Republic’, which he had never liked, by the ‘Fifth Republic’. Four years later, the French president also secured a plebiscite for Algerian independence.

In the De Gaulle tradition, most recent referenda called by European governments on constitutional issues have been intended to produce a ‘Yes’ vote. There is not usually much point in a political establishment going to the trouble of holding a referendum merely to prolong the status quo.

However, not everybody enjoys the enormous reputation of France’s legendary leader. More typically these days, the intentions of politicians are regarded with suspicion. The very fact that a referendum is held may be a sign of a government not sure of its ground. In the case of referenda involving international arrangements, the question to be asked may not be the product of satisfactory debate involving parliament and public. Both the decision to hold a referendum and the electorate’s response may be influenced by events in other countries. The Greek Cypriot referendum of April last year was arguably simply to defuse international pressure. For all these reasons, No votes – like accidents – happen.

The Turkish system

In Turkey, referenda have been few and far between. The liberal 1961 Constitution was approved by 62% of voters in July of that year. The highly restrictive constitution which replaced it was approved by 91% in November 1982. This new basic law banned the leading politicians of the pre-1980 era from taking part in politics for a period of ten years and permanently prevented any trial of the military leaders. The same Yes vote automatically made General Kenan Evren president of the Republic for a seven-year term. Restricted debate, the well-orchestrated support of the authorities and media for a Yes vote, the conduct of the voting and the fact that the only apparent alternative to the constitution was a more prolonged period of military rule all contributed to the outcome.

The 1982 constitution was not meant to be changed easily. It prescribes that amendments require a two-thirds majority in Parliament, and gives the president the right to put them to a referendum, even in cases where such a majority is obtained. In this way, referenda became an integral part of the political system, with binding results, and with no restrictions on the turn-out or the size of the majority required – but only for constitutional amendments, and only as one stage of an uphill process.

Over the years, the Constitution has been amended several times, often with a view to making it less restrictive. This has almost always been done without a referendum, thanks to consensus among the parties represented in Parliament and/or between political parties and the president.

Özal’s defeats

A constitutional amendment of May 1987 made it possible to change the constitution on the basis of only a three-fifths parliamentary majority provided both the president consents and the change is adopted by referendum. September of the same year brought the one constitutional change ever to have been made by referendum, when the public voted to lift the ten-year ban on the former politicians. This was, in a sense, a rebuff for the Turgut Özal government, which had no interest in seeing the names of Süleyman Demirel and Bülent Ecevit return to the ballot sheets in the next general election. But the margin was a dramatically slim 50.16%. Needless to say (?), a No vote would not have made the ban more democratic.

Özal instantly announced a snap general election, leaving his opponents minimum time to reorganise. Duly re-elected, he went on to sustain a 65% referendum defeat in September 1988 when he tried to bring forward the date of the next local elections (The Constitution fixes local elections at regular five-year intervals). The poll was one of history’s less crucial events: had the result gone the other way, citizens would have voted for their mayors, local councillors and muhtars in November 1998 instead of in March 1999.

Assessing risks

In 2003, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government introduced amendments to Articles 169 and 170 of the Constitution concerning forests. The aim was to allow so-called 2B properties – forest land which has become deforested – to be passed on to private developers, supposedly generating a huge income for the government. To sweeten the proposal, the AKP aimed to bundle the changes with an amendment reducing the voting age to 18. At the time, the AKP appeared to hold the necessary two-thirds majority in Parliament. But in the face of presidential opposition, it eventually fought shy of a referendum which would have turned into a “vote of confidence”. It would have been accused by all other parties of encouraging the burning of forests as well as seeking to pave the way for corruption.

In the AKP era, referenda have been suggested by government supporters and media commentators to by-pass the president on a range of other constitutional matters from secularism to his own powers of appointment. Another intriguing option would be to bring important constitutional changes onto the agenda between May 2007 and November 2007 – a period when, assuming both presidential and parliamentary elections are held on schedule, the AKP may have the benefit of a friendly president and still control a three-fifths parliamentary majority.

That said, the lesson of experience in both the EU and Turkey is that Yes votes require fine engineering. If European electorates are economically dissatisfied and inclined to punish their rulers, then the Turkish electorate – with its tradition of volatile swings away from ruling parties – can surely be relied on even less.

One cannot help wondering what would happen if Turkish citizens were asked to vote on whether to start accession talks with the EU now…

Interview

Mehmet Dülger: A voice for Parliament

by Bernard KENNEDY

Mehmet Dülger, chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament, comes from a political family. His father was almost executed with Prime Minister Adnan Menderes at Yassıada after the 1960 coup. A Swiss-educated architect, he himself succumbed to the lure – or duty – of politics as a newspaper director and then chief advisor to Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel in the 1970s. After the 1980 coup, Dülger became a founder and deputy leader of the True Path Party (DYP). The architect spent some time practising his profession after Demirel became President in 1993 and was replaced by Tansu Çiller as DYP leader. In 2002, he re-entered Parliament with the Justice and Development Party (AKP). “One of the reasons I am in politics is to make it a less risky occupation,” he declares. He names the failings of Turkish democracy as antipathy to rules, an emphasis on acquiring power – whether for use in the service of the people, of oneself or of one’s friends – and a constitution adopted under a military administration. Our conversation, however, focused on international issues and in particular the role of the Foreign Affairs Committee…

Q What role does the Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament play in making foreign policy?

A The Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament operates within a narrow framework. It discusses the international agreements which the government passes on to it. Those which it sees fit to approve then go to the General Assembly, and those which it does not see fit to approve either wait here or are sent back to the government.

When I became chairman of the Committee, a large backlog of agreements had built up over time. There was even one agreement which had been opened up for signatures in 1936. Working rapidly but carefully, we have now dealt with a high proportion of these accords. We have also done a lot of work related to the reform process.

Q How would you like to expand the role of the Committee?

A At the end of our first year, we called for legislation to make the Committee a place where foreign policy is discussed and debated to some extent, open to members of the Ministry concerned, and to writers, academicians, strategists and so on. This bill has not yet been submitted to Parliament. [If necessary,] I have decided to act as if the bill had become law. As of the coming term, the Foreign Affairs Committee is going to become a very interesting arena.

Q So the Committee would perform a kind of supervisory function?

A Not only that. In some countries like the USA there is a tactic which goes like this: You make a very reasonable request, and they say ‘OK, fine, but we have this awful Foreign Affairs Committee and we’ll never get them to approve it. So please show a bit of understanding.’ This gives the government a breathing space. We think we can perform this function too.

We would like to help the government to discuss its policies with [relevant parties]. Sometimes the government may take a step which at first glance appears unacceptable, but it may have its own reasons. So it would be able to explain itself here instead of somewhere else.

In the US, the Foreign Affairs Committee is very strong. Even the appointments of ambassadors have to be approved by the Foreign Affairs Committee. If only it were like that here…

Q How far is it possible to involve public opinion involved?

A I have a philosophy which I am personally trying to make sure that my party adopts. Generally, foreign policy falls within a government’s traditional policies. It is closely related to defence and so on. Nevertheless, I believe it should be as transparent as possible. After all, a bad foreign policy ultimately leads you to war. In war it is always the people that pay the highest price. But, for example, when you take a firm stance on a foreign policy issue, maybe the people don’t believe that is the right way to handle the issue. If you find out what the people want, then you can change your policy.

Before the famous March 1 vote in Parliament, I went to my constituency in Antalya, and asked them to listen to me explain the situation, and then to go away and sleep on it and consider their interests, and come to a conclusion with their families and friends, and decide whether I should vote Yes or No. In summary, what the people of Antalya said was this: ‘We don’t want a war. Tourism would suffer and there would be lots of problems for agriculture. As far as possible, try to avoid hostilities; try not to get involved in a war. But if you can’t manage it – if it can’t be done – then we will back you whatever decision you take.’ But at least I made up my mind after talking to my own people.

In foreign policy, I think you should go to the people and take their opinions, in exactly the same way as you do for economic policy or commercial policy. Once the Foreign Affairs Committee becomes an arena for ideas, then at the same time you will be learning what Turkey thinks outside Parliament – the views of the media, the academic world, people involved in strategic matters. As a result, you would develop better policies with a wider consensus.

Q What about the role of parliamentary delegations, friendship groups and so on?

A One of the things we are slowly trying to develop is what we call parliamentary diplomacy. This is a little more direct than governmental diplomacy. The sides can put their cases to one another even if they are sometimes far apart. An issue which may be difficult for diplomats to handle may be easy for parliamentarians, because you can’t deny that they represent the people… An agreement reached by way of parliamentary democracy can be very valuable because the member of parliament will then explain it to his own electors. This can lead us to follow more peaceful, softer policies.

Q Is there still an anti-American feeling in parliament? If the March 1 vote were held again would the result be the same?

A No, it is not a question of anti-Americanism. We have been loyal to our alliance with the US for 50 years. Paul Harris has called it a “troubled alliance”. Sometimes this is true but there are also times, such as the recent visit of US congressmen to Cyprus, when the US is closer to us than Europe. Iraq policy was a different matter. I think they realise that now.

Q It has been suggested that the Turkish parliament may issue retaliatory resolutions against parliaments that have passed Armenian “genocide” resolutions…

A At the moment there are no preparations for that. Where necessary, we are always on the side of the victims. But why should we make statements about history? When you talk to the French about Algeria, for example, they say, ‘Leave that to historians’. There is a double standard here. But we don’t need to get fanatical like some of the French….

Q What, briefly, are your thoughts on the future of the EU after the French No vote on the proposed constitution?

A …Until now, the newcomers to the EU have had to change and the EU has stayed the same. Now the EU will have to change… From a very broad perspective the No vote can be looked on as a childhood disease. Such an integration project is being attempted for the first time in the world, and it may take 100 years for everybody to feel the same way about it. The EU has gone a long way towards integration […but…] it has become detached from the people. Consequently [the referendum outcome] will certainly increase the importance of the European Parliament.

Human angle

The sociological void in the GME Project

by Prof. Dr. Özer OZANKAYA

The US and other Western governments have devised a strategy known as the “Greater Middle East Project” for the Muslim countries which they have colonised directly or indirectly for more than a century. On paper, they seek to establish self-governing democracies in a region extending from Morocco to Indonesia, and including the Caucasus and Central Asia. Yet they also speak of “moderate Islamic governments”. It is a complete contradiction in terms!

The idea of a public order based on Islam, moderate or otherwise, impedes from the start the contributions that the science of sociology can make to the establishment of the social order. In his classic work “The Division of Labour in Society”, Emile Durkheim states that “Of all the elements of civilization, science is the only one which, under certain conditions, presents a moral character. That is, societies are tending more and more to look upon it as a duty for the individual to develop his intelligence by learning the scientific truths which have been established. Science is nothing else than conscience carried to its highest point of clarity. Thus in order for societies to live under existing conditions, the fields of conscience, individual as well as social, must be extended and clarified. The more obscure conscience is, the more refractory to change it is. That is why intelligence guided by science must take a larger part in the course of collective life.”

Reason versus religion

The chief advocate of the Greater Middle East Project, President George Bush of the USA, says he is not following science but rather Jesus. For this reason, he deems “moderate Islamic government” appropriate for the Islamic world. But for Durkheim, “If there is one truth that sociology teaches us beyond doubt on historical dimension, it is that religion tends to embrace a smaller and smaller portion of social life. Originally it pervades everything; everything social is religious; then, little by little, political, economic, scientific functions free themselves from the religious function, constitute themselves apart and take on a more and more acknowledged temporal character… It has sometimes been said that free thought makes religious beliefs regress, but that supposes, in its turn, a preliminary regression of these same beliefs. It can arise only if the common faith permits.”

Innumerable Muslims have themselves come to a similar conclusion. The use of the printing press was forbidden in the Turkish and Islamic world for almost 400 years from the 15th century onwards, preventing the enlightenment of the masses. İbrahim Müteferrika established the first printing machine in the Islamic world in Istanbul in 1726. Before his machine was burnt and destroyed a few years later, he printed a book explaining the weak and backward condition of the Islamic World compared to the West in terms of the absence of reason from the realm of thought. In “Rational Bases for the Polities of Nations” Müteferrika argues as follows:

“The rules necessary for the ordering of all Christian nations do not exist in their religious books; the current order of their states are immediately dependent on a series of rules based on reason; they have no thought of awaiting reward or payment in the next world… They have firmly disciplined their armies with laws and rules based on reason… Islamic nations have been entirely careless, inattentive and thoughtless in the face of the condition of the peoples referred to, and have refused to understand their attitude towards our country or the essence of their situation, preferring unmitigated bigotry and insisting on remaining ignorant.”

Islam’s secular potential

Islam is not a religion incompatible with science, freedom and a democratic and secular social and state establishment. It was a force for freedom during the period of its establishment. It created a bright civilization which benefited from the ideas of the Ancient Greeks without prejudice, and which preserved them for the West while it endured the bigotry of Middle Ages, thereby contributing to the formation of the atmosphere in which the revolutions of the Renaissance and Reformation took place. Islam does not envisage a class of clergy with privileged knowledge of God, but rather considers every individual to have the maturity of mind and superiority of consciousness needed to distinguish good from bad. It has no places of worship like churches where attendance is compulsory, but envisages that prayer be performed without ostentation, averting all pressures on the individual conscience.

In this context, let us recall Ibn Rushd, whose words “The universe has not been created, because it has been always there!” and “Verses of the Koran should not be used as an evidence in my madrasah” prefigured Lavoisier’s “Nothing is lost, nothing is created”; and can be seen as the source of inspiration for Lessing’s “What is the value of believing without asking evidence?” . Nor let us forget the universal values of Islam expressed by Yunus Emre – for example in the lines “Whatever you wish for yourself/ Wish for the others/ This is the meaning of the four books/ If there is any meaning.”

Such a religion, far from being opposed to democracy and secularism, makes these the essential form of social order. So why “moderate Islam”? Why does the West not simply declare itself for secularism and refrain from condoning medieval-minded public institutions and the practices which control them, from sheikhdom, sectarianism, religious education, opposition to the freedom of thought and the frequenting of tombs and healers to a family structure which places women in chains and seeks to base economic institutions on religious rules?

Chains of colonialism

Words spoken by Mustafa Kemal 80 years ago provide the essential clue: “The hundreds of millions of Muslim masses on earth are in chains of captivity and subservience to somebody or other. The spiritual education and morality which they have received has not given them the necessary human quality to break these chains of captivity, nor can it!” If one problem facing the integration of the Islamic world into the civilised family of society is the widespread mode of thought of a Muslim world anchored to the Middle Ages, the other side of the coin is the mentality of the Political West which does not regard colonialism as shameful!

Müteferrika’s extremely important warning failed to prompt an intellectual movement. Its outdated structure also caused the Islamic world to be excluded entirely not only from printing machine but also from the trends of the Renaissance and Reformation, from geographical discoveries and from scientific inventions in the West. Although a century later, during the Tanzimat period, efforts at modernization started to be witnessed, the Ottoman state and the Islamic countries had by then become colonies of Western Europe anyway. Like all oppressive governments, the rulers of these countries, insisted on their old feudal structure and started to cooperate with the colonialists.

The Islamic world – with the sole exception of the Turkey of Atatürk’s – was unable to understand – or prevented from understanding – the real cause of the destruction it had undergone. Capitalist powers, in turn, are far from repudiating their colonial heritage and habits – let alone from putting science and technology to best use in the service of freedom, equality, justice, peace and common welfare, particularly on the international plane.

Durkheim’s moral anomie

This issue is referred to by Emile Durkheim in his aforementioned work as “the state of legal and moral anomie that economic life is in”. “The most blameworthy acts,” he asserts, “ are so often absolved by success that the boundary between what is permitted and what is prohibited, what is just and what is unjust, has nothing fixed about it, but seem susceptible to almost arbitrary change by individuals… It is this anomic state that is the cause of the incessantly recurrent conflicts and the multifarious disorders of which the economic world exhibits so sad a spectacle… Human passions stop only before a moral power they respect. If all authority of this kind is wanting, the law of the strongest prevails, and latent or active, the state of war is necessarily chronic…To justify this chaotic state; we vainly praise its encouragement of individual liberty. Nothing is falser than this antagonism too often presented between legal authority and individual liberty. Quite on the contrary, liberty (we mean genuine liberty, which it is society’s duty to have respected) is itself the product of regulation… It is impossible for the State not to be interested in a form of activity which, by its very nature, can always affect all society…”

The only project able to improve the lot of Muslims and to integrate them into the modern world is the secularist path, which permits the development of a social order based on the science of sociology. This is compatible with Islam but requires a different attitude form the Political West.

The lives of societies are determined in part by material (economic and technological) forces, and in part by forces of thought and ideas. Unless the fabric of a society is not distorted by outside factors, these two groups of factors normally form a harmonious whole. If an order genuinely based on democracy – on independence, freedom, justice and welfare – is to be established in the large area of our world referred to as the “Greater Middle East”, the forces of thought should be such as to achieve, and not obstruct, these ideals.

World view

Africa, Turkey – and a personal touch

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV

“…As I see the early rays of the sun coming up and chasing the darkness of the night away, I envisage with equal certainty that all the colonial peoples will drive foreign exploitation out and attain their deserved independence and freedom…” It is on record that these prophetic words were uttered in March 1933, at the end of a high-level meeting that continued until day-break, by none other than the great M. Kemal Atatürk, the illustrious leader of our National Liberation Struggle (1919-22) and the founder of our Republic (1923). Ours was the first successful anti-imperialistic struggle of modern times, and it served as a pioneering model for all peoples striving to throw off colonial and the imperialistic yokes.

What Kenyatta knew

During the visit of a Turkish delegation to Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, the first prime minister (1963-64) and then president (1964-78) of that country, told his listeners how Turkey had been faced with foreign intervention but had resisted all assaults. When one of those present expressed his surprise at the Kenyan leader’s command of Turkish history, Kenyatta retorted: “I am not an expert on the history of the Turks; but I am well-read on the records of anti-imperialistic struggles. What I know is that history, in which the Turks wrote glorious pages.”

When I was in Tripoli in 1981, to attend the Asia-African Philosophy Conference, which coincided with the centenary of Atatürk’s birth, I phoned the Editor-in-Chief of The Nation to inform him that I had prepared a special article for his paper on the Turkish leader. At the same time, I narrated the Kenyatta episode. The publisher immediately assured me that he had himself witnessed those remarks. He was the President’s press attaché at the time, and had been in attendance. He printed my article on the editorials page the next day.

Academic approach

As Ottoman Turks in particular, we knew North Africa quite well. Our first appearance there in 1517 – in response to Western European incursions designed to encircle the Muslim lands – added Egypt and the seat of the Caliphate to our Empire. Eventually, Ottoman sovereignty touched the Moroccan borders in the far West. Even Karl Marx, one of the foremost analysts of discrimination and exploitation, stated that Ottoman rule could not be compared to the subsequent European colonialism either in that region or in the other parts of the globe.

Although some Arab geographers further divide North Africa into sub-regions, such as “Jazirat al–Maghrib” (meaning Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco), I have always chosen to treat the continent as a whole. This was my academic approach when I prepared The African National Liberation Movements, a 705-page textbook, for my course on Africa at Ankara University. Atatürk’s guiding statement, quoted above, was printed on the back cover of the book.

Six pioneers

I introduced this course, initially as a graduate seminar, in the year 1960, when there were only six independent African states. They were:

— Ethiopia – also known in the past as Abyssiania – with which we had age-old relations since Ottoman times, and a complete identity of vital interests, especially against Mussolini’s fascism;

— Liberia, founded in 1847 by freed black slaves from the southern USA who had first settled along the western Guinea coast;

— Egypt, which had experienced a high degree of cultural individuality before the coming of the Muslim Arabs, a golden age under the early Fatimids, a long Ottoman period, British rule, independence (1922) and finally continental leadership after the “Free Officers” Revolution (1952);

— Libya, where the majority were Muslims, and which had been ruled by the Karamanlı dynasty of Ottoman origin or directly by the Porte until the Italian invasion (1911), then achieved a Revolution (1959) remarkable for the absence of opposition, fighting or deaths;

— South Africa, which later overthrew the apartheid regime – an extreme formulation of segregationist principles adopted by all governments since the Union (later Republic – 1961), and

— Ghana, the famous “Gold Coast”, which possessed a respectable tradition of protest against British colonialism, and which had adopted the slogan of “Self-Government Now”, and attained independence in 1957.

The EAFORD years

Later, my course became a fully-fledged undergraduate course, the first and only one in the whole network of the Turkish universities. This interest of mine, coupled with other publications and activities, led to my election to the newly-founded (1976) Central Executive Council of the “International Organization for the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination”, known for short as EAFORD. A UN affiliate, EAFORD, which met in an African capital, now has a Secretariat in Geneva, and formerly had chapters in London, Paris, Quebec, and Washington, D.C.. It organized several international conferences and printed various books and booklets.

My own publications under EAFORD’s roof include several books and booklets printed in the UK, Canada, the USA, Switzerland and Libya. It was on account of activities of this kind that I was to receive an academic award from the University of Bophuthatswana (South Africa) which reads: “This Citation of Meritorious Contribution to African Scholarship and Research is awarded for his Service to the African Phenomenon which spans some 30 years…”

After apartheid

When I started my first course on Africa, Nelson Mandela had not yet been arrested (1962). While he spent long 27 years behind bars, becoming an international cause célèbre in the meantime, some of us worked for three decades to help bring about the transition to non-racial democracy. Consequently, I was his government’s guest (the only Turk besides Mrs. Ataöv) at that historic session of parliament that ended apartheid. Having considered the treatment of the Palestinians as another form of racial discrimination, I may add that Chairman Yasser Arafat responded to my equally sincere endeavours in support of Palestinian rights with the award of a “Medal of Honour”, conferred on me in his Tunis headquarters.

It gave us Turks great pleasure to host speeches and a reception marking the occasion of “Africa Day 2005” in our capital last month. Atatürk’s prophecy has certainly materialised. The “crowns” are now on the heads of the majorities of the African peoples. What should be watched from now on is to see that their jewels are also evenly distributed.

Speaking Out

Ambassador Mohamed Lessir: Acting on information

A former ambassador to London, Ambassador Mohamed Lessir was the first newly-arrived envoy to present his credentials to President Ahmet Necdet Sezer a full five years ago. His country, Tunisia, straddles Africa and the Middle East, yet lies only 140 kilometres across the Mediterranean from Europe. Famous for its oranges, olive oil and dates, it is today heavily engaged in the digital revolution and the future of Africa…

- Bilateralrelations

Turkey and Tunisia have always had good relations. Aside from the long Ottoman presence in Tunisia, there are certain moments in our common history which cannot be forgotten. Almost 2,200 years ago, the great strategist and warrior, Hannibal of Carthage, finally poisoned himself in Gebze, near Istanbul. We are grateful to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk for ordering a modest mausoleum to be built for him. A second link was forged between Turkey and Tunisia when Tunisia sent 12,000 soldiers to fight against the Russians in the Crimean War. Some of the survivors later settled in Kastamonu. When I visited Kastamonu, I met many people who said they were of Tunisian origin.

Thirdly, there is the great nineteenth century reformer Hayreddin Pasha, who imported many reforms from the West to Tunisia, and later continued his reforms as sadrazam in Istanbul. Turkey and Tunisia have continued to see eye-to-eye on social reforms. You can see in both countries how adamant we have been in women’s liberation. It is the magic of the alphabet that we also sit by side in the list of nations.

Politically relations are excellent. President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali visited Turkey in March 2001, President Ahmet Necdet Sezer reciprocated in May 2003, and in March 2005 Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Tunisia. Foreign Minister Abdelbaki Hermassi was here in February. In April we had a very, very successful film festival, which I inaugurated together with Minister of State Kürşad Tüzmen. What we need now is the cement of economic relations and trade. The signing of a Free Trade Agreement in November 2004 marks a milestone in our economic relations. Now the ball is in the court of the businessmen.

We have a deficit in our trade with Turkey. On the other hand, there are about fifteen projects, joint ventures and direct investments by Turkish companies in Tunisia. There is room for more. With the aid of generous incentives, Tunisia obtains close to US$1bn per year in foreign investment – a high figure for a country of ten million people. There are 62 industrial zones, two free zones – and 2,532 foreign companies. Tunisia provides the stability which investors need. It’s an excellent base from which to enter Africa.

Given our common heritage we should be exchanging more tourists. There are already ten flights a week between the two countries. About 50,000 Tunisians visit Turkey each year. Most go to Istanbul on shopping trips. Many of them are traders who spend money and then pay Tunis Air and Turkish Airlines for excess baggage. But in return only 12-13,000 Turks visit Tunisia.

The textiles industry is very important for both countries. Tunisia, for example, is the leading exporter of trousers to France. Chinese products are very competitive. We are having contacts about this, but the answer won’t be to bring back quotas. So we envisage some co-operation schemes to lower costs and make us more competitive.

- Africa’s agenda

People tend to see Africa as a disease- and conflict-ridden continent with no prospects for peace and security. At the moment there are troubles in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Ivory Coast and Sudan. We are hoping that the African Union will do better in the future in terms of establishing stability. But other continents have gone through much strife and revolution as well. In time, I think, given a bit of stability, if African countries can put their act together, they can enjoy good prospects. There are numerous African countries which are stable and which you don’t hear about because they are making progress. And of course Africa is well endowed with natural resources to exploit.

Africans believe in elections and transparent government. This is not dictated by foreign powers. There is a scheme within the Union for monitoring human rights, good governance and fair elections. There is also an African Commission on Human Rights. And there are innumerable African NGOs dealing with development, education, the treatment of children and women and many other issues. Hope can spring afresh, and a new day can dawn.

The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) is an initiative of the Union to provide an integrated socio-economic development framework for Africa. It is also seeking to determine how the G-8 and other countries could help the Continent to emerge through more democracy, more transparency, the elimination of corruption and the promotion of health and education. Why not consider a Marshall Plan for Africa, since Africa is so important for the big powers, so that Africa does not get marginalised again?

The eight African countries represented in Ankara – Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tunisia – have formed a small group to speak in the name of Africa. I am the dean of the African ambassadors because I have been here the longest. We were very much encouraged when Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government declared 2005 the “Year of Afrıca”. Turkey has not shown a great interest in Africa in the past, but Mr Erdoğan has travelled to Ethiopia and South Africa and recently visited Tunisia and Morocco. A visit to Kenya and a couple of other visits are in the pipeline.

In May we organised a series of Africa Day events in order to increase our visibility. We think Turkey and Africa can do a lot of things together. Turkey has very powerful companies in the field of infrastructure. We would like to form partnerships and take advantage of that know-how. The technical cooperation agency TICA, heavily present in Central Asia, is moving into Africa too. Tunisia has a similar agency. I think there is work for everyone. We could work together to carry out education, health and women’s programmes and to build bridges, roads and schools.

- Information summit

Phase Two of the World Summit on the Information Society is to be held in Tunis on November 16-18, 2005. President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali is very interested in technology. At the International Telecommunication Union summit in Minneapolis in 1998, the President proposed a summit on the information society. The first phase took place in December 2003 in Geneva. Intensive preparations are now under way for the second phase.

The developing countries want to bridge the digital divide from the beginning. You do not have to have had an agricultural revolution or an industrial revolution to do well in this field. It doesn’t take a lot of investment. It’s a question of education and science. Tunisia exports a lot of produits de l’intelligence. So do countries like Bangladesh, not to speak of India.

The Third World has been marginalised before, and in many countries there is disease, violence and conflict, which poses a threat to World stability. A repetition is not in the interests of the developed countries. Spreading the information society can make the world a more peaceful place. I am not being romantic – merely logical. We must not give arguments to those who would like to blow up the world and all civilisation for the sake of an idea in the back of their heads.

In 1993, Tunisia set up a National Solidarity Fund (NSF). It attracts large donations on December 7 every year, and has reduced poverty to just 4%. There are now similar funds in many African countries. Some years ago, we suggested a World Solidarity Fund, and the UN has passed a resolution on the subject. At Geneva, we proposed a “Digital Solidarity Fund” This has now been established and will be discussed further at November’s summit.

Another important topic is the governance of the Internet. People are aware that you can’t really control the Internet. Nevertheless, it is being used by criminal organisations and pornography rings. This is recognised as a problem in the developed countries as well as the Third World and the Islamic world. Some rules – for want of a better word –need to be laid down. But agreement will have to be reached not just with governments but also with civil society, which is very concerned about the freedom of the Internet.

I must emphasise that the summit is not intended only for heads of state, government officials and international organisations. NGOs, the media and the business community will also have a major presence. Parallel activities include a major exhibition, workshops and a partnership area. We hope that the summit will act as a magnet to attract big names to Tunisia and to Africa. We would like to see a high level of business participation as well as a sizeable contribution from the developed world to do something to bridge the gap. I think it’s going to be a very big event.

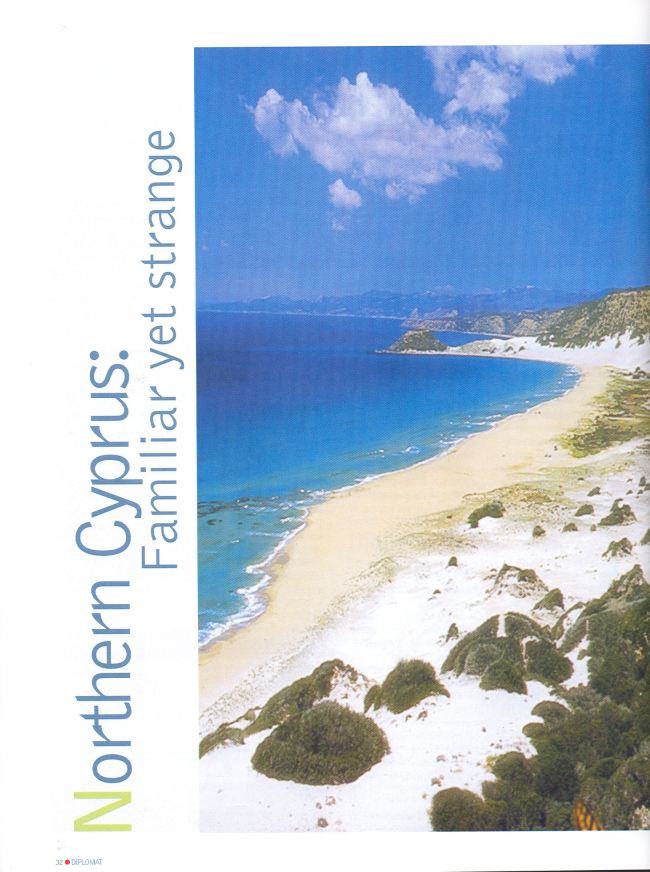

Northern Cyprus: Familiar yet strange

Only 65km south of the Turkish Mediterranean coast lies a country where the sea is a deeper blue, the architecture speaks of a different past and Turkish is spoken with an alternative intonation. Often visited in private by diplomats resident in Turkey, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus turns out to offer more variety and surprises than its small size and its physical and cultural proximity would suggest.

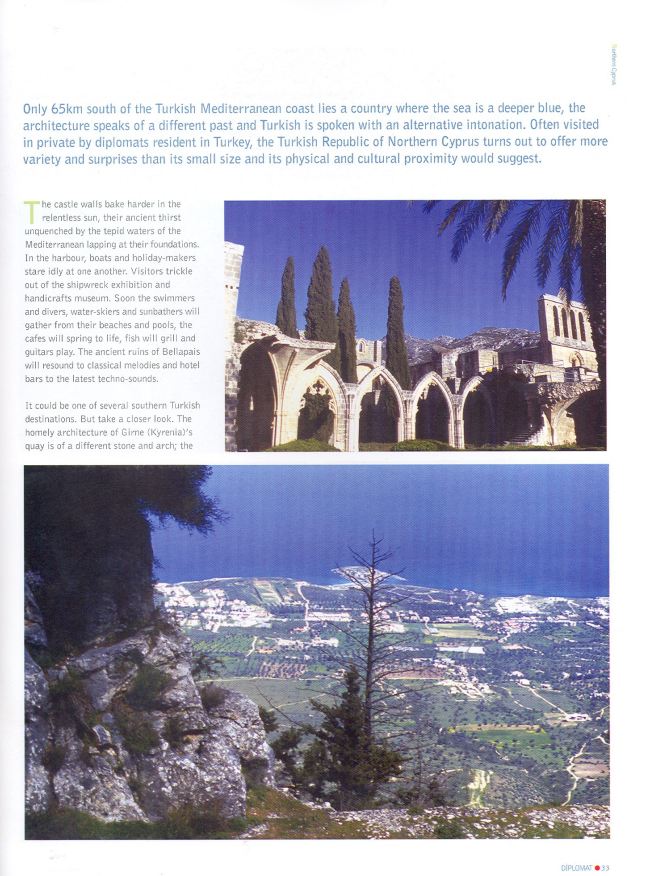

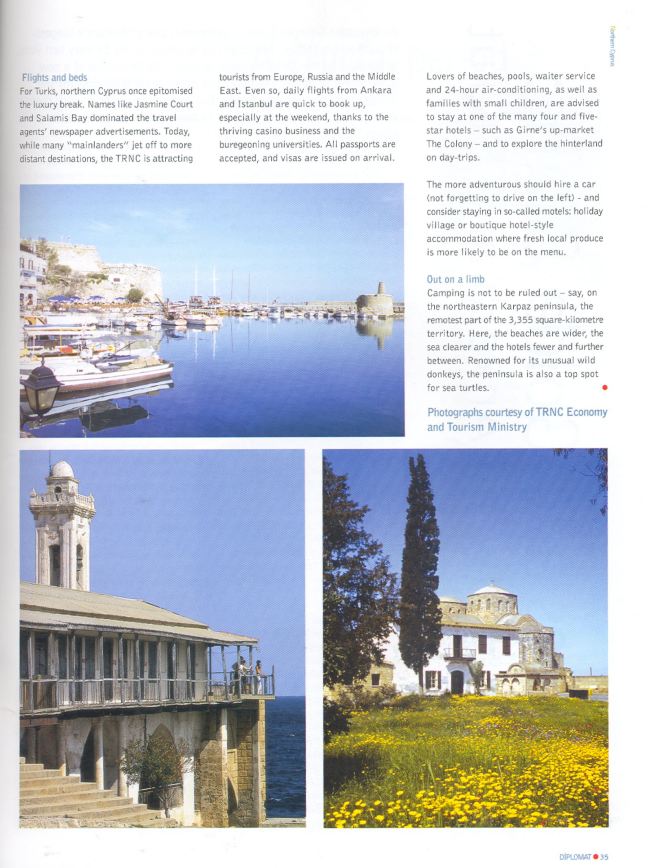

The castle walls bake harder in the relentless sun, their ancient thirst unquenched by the tepid waters of the Mediterranean lapping at their foundations. In the harbour, boats and holiday-makers stare idly at one another. Visitors trickle out of the shipwreck exhibition and handicrafts museum. Soon the swimmers and divers, water-skiers and sunbathers will gather from their beaches and pools, the cafes will spring to life, fish will grill and guitars play. The ancient ruins of Bellapais will resound to classical melodies and hotel bars to the latest techno-sounds.

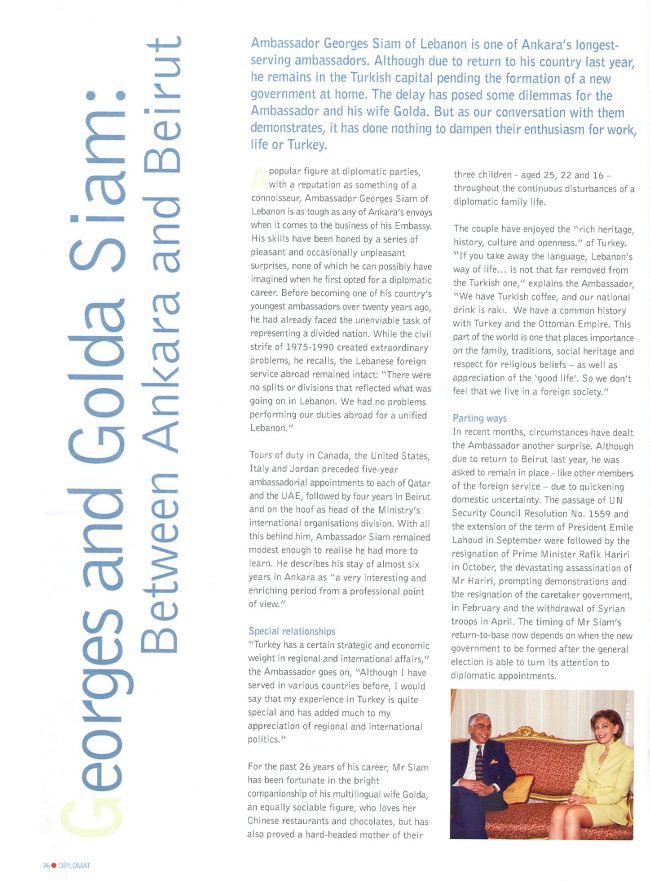

It could be one of several southern Turkish destinations. But take a closer look. The homely architecture of Girne (Kyrenia)’s quay is of a different stone and arch; the seventh-century castle bears imprints of Lusignans, Genoese and Venetians – and Bellapais is a medieval monastery, first built for migrant priests from Jerusalem, the expanded by Hugh III of France.

Gothic mosques, hill-top hideouts

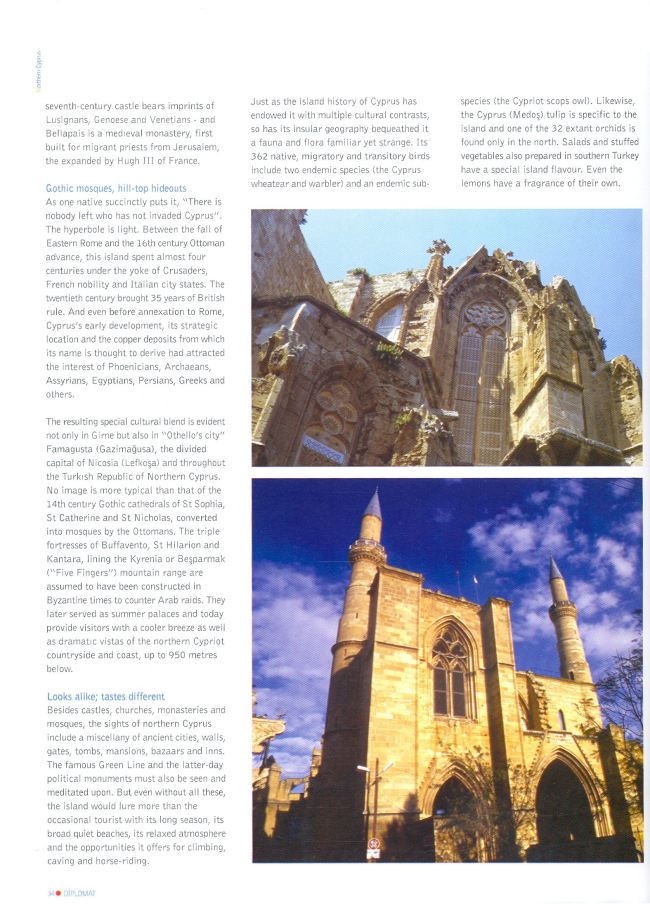

As one native succinctly puts it, “There is nobody left who has not invaded Cyprus”. The hyperbole is light. Between the fall of Eastern Rome and the 16th century Ottoman advance, this island spent almost four centuries under the yoke of Crusaders, French nobility and Italian city states. The twentieth century brought 35 years of British rule. And even before annexation to Rome, Cyprus’s early development, its strategic location and the copper deposits from which its name is thought to derive had attracted the interest of Phoenicians, Archaeans, Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Greeks and others.

The resulting special cultural blend is evident not only in Girne but also in “Othello’s city” Famagusta (Gazimağusa), the divided capital of Nicosia (Lefkoşa) and throughout the Turkısh Republic of Northern Cyprus. No image is more typical than that of the 14th centıry Gothic cathedrals of St Sophia, St Catherine and St Nicholas, converted into mosques by the Ottomans. The triple fortresses of Buffavento, St Hilarion and Kantara, lining the Kyrenia or Beşparmak (“Five Fingers”) mountain range are assumed to have been constructed in Byzantine times to counter Arab raids. They later served as summer palaces and today provide visitors wıth a cooler breeze as well as dramatic vistas of the northern Cypriot countryside and coast, up to 950 metres below.

Looks alike; tastes different

Besides castles, churches, monasteries and mosques, the sights of northern Cyprus include a miscellany of ancient cities, walls, gates, tombs, mansions, bazaars and inns. The famous Green Line and the latter-day political monuments must also be seen and meditated upon. But even without all these, the island would lure more than the occasional tourist with its long season, its broad quiet beaches, its relaxed atmosphere and the opportunities it offers for climbing, caving and horse-riding.

Just as the island history of Cyprus has endowed it with multiple cultural contrasts, so has its insular geography bequeathed it a fauna and flora familiar yet strange. Its 362 native, migratory and transitory birds include two endemic species (the Cyprus wheatear and warbler) and an endemic sub-species (the Cypriot scops owl). Likewise, the Cyprus (Medoş) tulip is specific to the island and one of the 32 extant orchids is found only in the north. Salads and stuffed vegetables also prepared in southern Turkey have a special island flavour. Even the lemons have a fragrance of their own.

Flights and beds

For Turks, northern Cyprus once epitomised the luxury break. Names like Jasmine Court and Salamis Bay dominated the travel agents’ newspaper advertisements. Today, while many “mainlanders” jet off to more distant destinations, the TRNC is attracting tourists from Europe, Russia and the Middle East. Even so, daily flights from Ankara and Istanbul are quick to book up, especially at the weekend, thanks to the thriving casino business and the buregeoning universities. All passports are accepted, and visas are issued on arrival.

Lovers of beaches, pools, waiter service and 24-hour air-conditioning, as well as families with small children, are advised to stay at one of the many four and five-star hotels – such as Girne’s up-market The Colony – and to explore the hinterland on day-trips. The more adventurous should hire a car (not forgetting to drive on the left) – and consider staying in so-called motels: holiday village or boutique hotel-style accommodation where fresh local produce is more likely to be on the menu.

Out on a limb

Camping is not to be ruled out – say, on the northeastern Karpaz peninsula, the remotest part of the 3,355 square-kilometre territory. Here, the beaches are wider, the sea clearer and the hotels fewer and further between. Renowned for its unusual wild donkeys, the peninsula is also a top spot for sea turtles.

Georges and Golda Siam: Between Ankara and Beirut

by Bernard KENNEDY

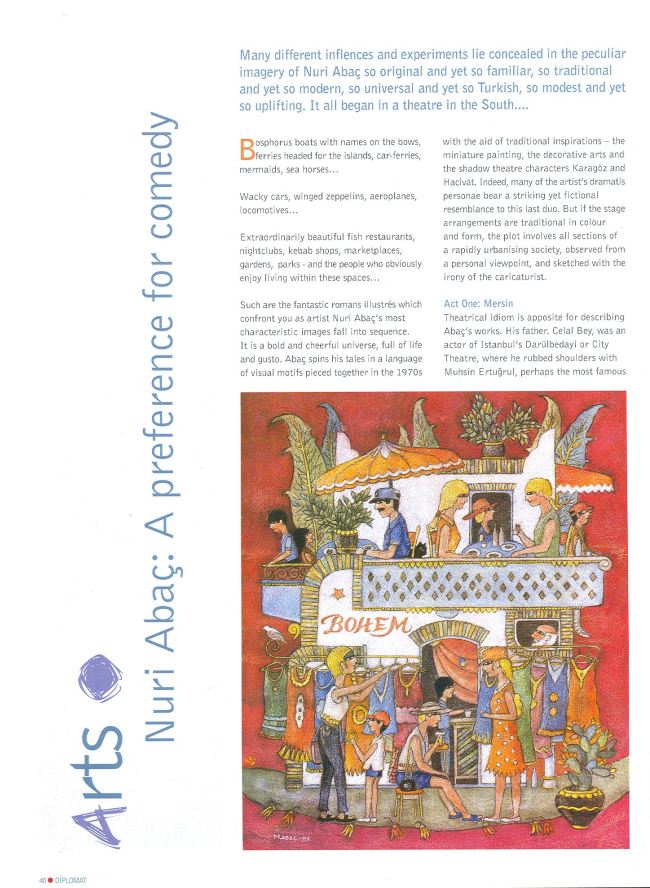

Ambassador Georges Siam of Lebanon is one of Ankara’s longest-serving ambassadors. Although due to return to his country last year, he remains in the Turkish capital pending the formation of a new government at home. The delay has posed some dilemmas for the Ambassador and his wife Golda. But as our conversation with them demonstrates, it has done nothing to dampen their enthusiasm for work, life or Turkey.

A popular figure at diplomatic parties, with a reputation as something of a connoisseur, Ambassador Georges Siam of Lebanon is as tough as any of Ankara’s envoys when it comes to the business of his Embassy. His skills have been honed by a series of pleasant and occasionally unpleasant surprises, none of which he can possibly have imagined when he first opted for a diplomatic career. Before becoming one of his country’s youngest ambassadors over twenty years ago, he had already faced the unenviable task of representing a divided nation. While the civil strife of 1975-1990 created extraordinary problems, he recalls, the Lebanese foreign service abroad remained intact: “There were no splits or divisions that reflected what was going on in Lebanon. We had no problems performing our duties abroad for a unified Lebanon.”

Tours of duty in Canada, the United States, Italy and Jordan preceded five-year ambassadorial appointments to each of Qatar and the UAE, followed by four years in Beirut and on the hoof as head of the Ministry’s international organisations division. With all this behind him, Ambassador Siam remained modest enough to realise he had more to learn. He describes his stay of almost six years in Ankara as “a very interesting and enriching period from a professional point of view.”

Special relationships

“Turkey has a certain strategic and economic weight in regional and international affairs,” the Ambassador goes on, “Although I have served in various countries before, I would say that my experience in Turkey is quite special and has added much to my appreciation of regional and international politics.”

For the past 26 years of his career, Mr Siam has been fortunate in the bright companionship of his multilingual wife Golda, an equally sociable figure, who loves her Chinese restaurants and chocolates, but has also proved a hard-headed mother of their three children – aged 25, 22 and 16 – throughout the continuous disturbances of a diplomatic family life.

The couple have enjoyed the “rich heritage, history, culture and openness.” of Turkey. “If you take away the language, Lebanon’s way of life… is not that far removed from the Turkish one,” explains the Ambassador, “We have Turkish coffee, and our national drink is rakı. We have a common history with Turkey and the Ottoman Empire. This part of the world is one that places importance on the family, traditions, social heritage and respect for religious beliefs – as well as appreciation of the ‘good life’. So we don’t feel that we live in a foreign society.”

Parting ways

In recent months, circumstances have dealt the Ambassador another surprise. Although due to return to Beirut last year, he was asked to remain in place – like other members of the foreign service – due to quickening domestic uncertainty. The passage of UN Security Council Resolution No. 1559 and the extension of the term of President Emile Lahoud in September were followed by the resignation of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in October, the devastating assassination of Mr Hariri, prompting demonstrations and the resignation of the caretaker government, in February and the withdrawal of Syrian troops in April. The timing of Mr Siam’s return-to-base now depends on when the new government to be formed after the general election is able to turn its attention to diplomatic appointments.

Mrs Siam and their younger daughter, however, are on the move. As the baccalaureat approaches, she explains, “I can’t take the risk of changing schools in the middle of the academic year.” Accordingly, she will be working on their new apartment and hoping for visits from her elder children currently studying in Canada and France, while “leaving [the Ambassador] in good hands and preparing the ground for his homecoming.”

“I will miss all our friends,” says Mme Siam, “It is friends that makes any place special. But funnily enough, because Lebanon is so close to Turkey, in a way we feel we can come back any time and relive the good memories. Turkey is a place you can’t simply remove from your mind. People are very hospitable and there are so many places to visit. I hope we’ll keep in touch. I also want some of my friends to come and visit Lebanon.”

Unfinished business

The Ambassador will have plenty to keep him occupied. When we spoke to him he was excited about the prospect of a trip to Lebanon by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Before the death of Hariri, Turkey and Lebanon were about to conclude talks on a free trade agreement, and a number of other accords signed last year await full implementation. Re-generating the momentum of business ties and tourist visits and building on the Arab-Turkish summit which took place in Istanbul in early May are also among the Lebanese envoy’s priorities. After the election and the setting up of a new government in Lebanon, he says, there is every reason to believe that cooperation will go back to usual. “We have never had serious issues or differences with Turkey. Turkey has always been supportive of Lebanon in regional and international instances… and of course we look at Turkey as a regional power which can be useful in bringing peace and stability.”

And are any of the couple’s children considering a diplomatic career? “They are very open to different cultures and glad that they have experienced the richness of a diplomat’s life,” replies Ambassador Siam. “But no, I think they would like to settle down and lead a normal life.”

A crucial period

Ambassador Siam also expressed his views on a range of issues concerning Lebanon and the international community.

Q How would you characterise the current political situation in Lebanon?

A We are going through a very crucial period. For the first time in so many years the Lebanese feel that they have the responsibility of taking the destiny of their country in their own hands. It is an opportunity to prove that we can put the country back on its feet and on the regional and international map. It’s not easy to exercise freedom and democracy in this part of the world. There has been much interference in our political life, and Lebanese society is very diverse. However, we can be proud of our national and democratic heritage. We have had a democratic process for many years. The rights of women and human rights in general are observed and respected. Freedom of religion, expression and the media are all part of our national heritage. I am sure many countries in the area look at Lebanon as a unique experience and would like to follow our footsteps. We hope to be able to present an example of peaceful coexistence between different communities.

Q Is there any indication of who was responsible for the bomb attack which killed Prime Minister Hariri?

A An international investigation team sent by the United Nations is working on it. The Lebanese authorities will extend every possible help. It is very easy to speculate but more difficult to find evidence. The departure of Mr Hariri was a great loss not only at the national level but also at the regional and world level. He was a political and economic heavyweight who called for regional and international cooperation and was a driving force behind major economic opportunities for Lebanon and the region. He was also a champion of close ties between Lebanon and Turkey.

Q Will the army now be deployed in southern Lebanon?

A The army is already deployed in the south of Lebanon. It’s not a no-man’s-land. However, in certain areas the United Nations is assuming the responsibility of keeping things quiet. When we are able to resolve the issue of the remaining occupied parts of our territory – namely the Shebaa Farm and surrounding areas – then the army will be in a better position to deploy further southward.

Q Will Lebanon continue to maintain good relations with Syria?

A This is a delicate period but we will definitely be able to overcome any misunderstandings that have resulted from the recent developments and to restore our relations back to a normal level because ultimately this is what history and geography requires.

Q What about the Palestinian issue?

A There is no major problem resulting from the Palestinian presence in Lebanon for the time being. Nevertheless, we hope for a quick solution to enable the Palestinian refugees that live in Lebanon to return to their homeland. We cannot integrate a large number of Palestinians into our national life, but they should not live in refugee camps for ever. It is the responsibility of the countries of the region and the international community to bring the peace process to a happy end. That said, we have no reason to be optimistic at this point.

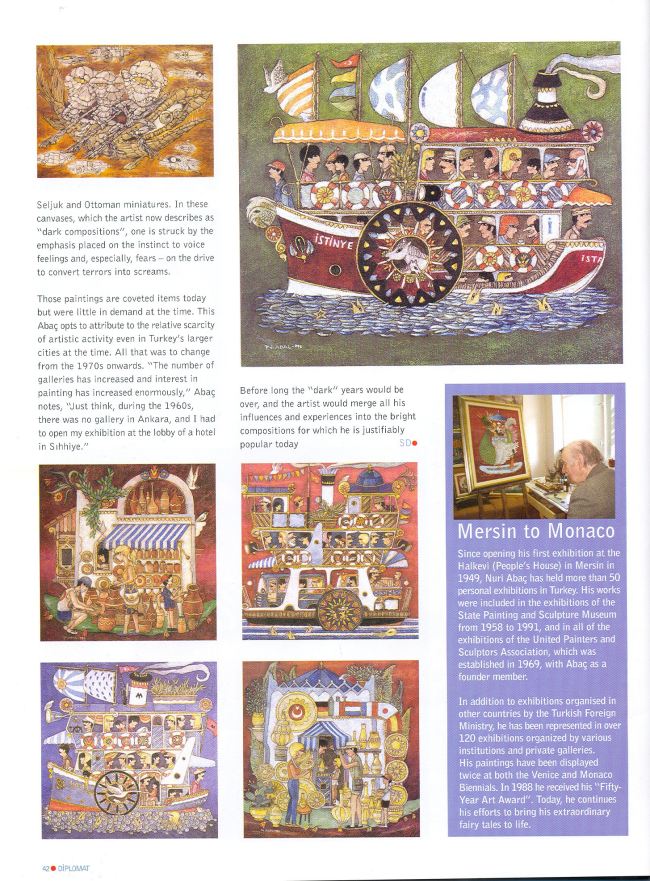

Nuri Abaç: A preference for comedy

by Sibel DORSAN

Many different inflences and experiments lie concealed in the peculiar imagery of Nuri Abaç so original and yet so familiar, so traditional and yet so modern, so universal and yet so Turkish, so modest and yet so uplifting. It all began in a theatre in the South….

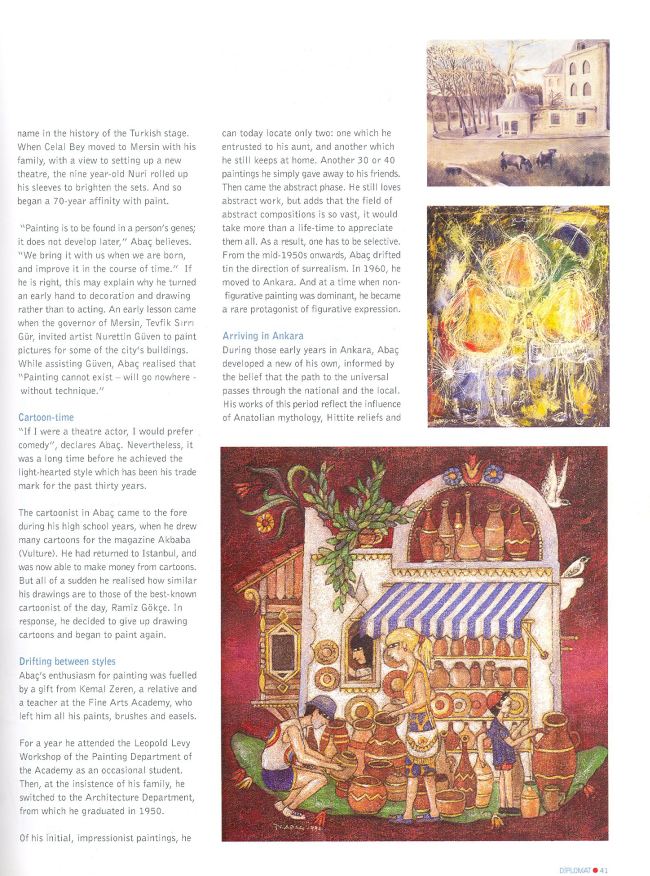

Bosphorus boats with names on the bows, ferries headed for the islands, car-ferries, mermaids, sea horses…

Wacky cars, winged zeppelins, aeroplanes, locomotives…

Extraordinarily beautiful fish restaurants, nightclubs, kebab shops, marketplaces, gardens,

parks – and the people who obviously enjoy living within these spaces…

Such are the fantastic romans illustrés which confront you as artist Nuri Abaç’s most characteristic images fall into sequence. It is a bold and cheerful universe, full of life and gusto. Abaç spins his tales in a language of visual motifs pieced together in the 1970s with the aid of traditional inspirations – the miniature painting, the decorative arts and the shadow theatre characters Karagöz and Hacivat. Indeed, many of the artist’s dramatis personae bear a striking yet fictional resemblance to this last duo. But if the stage arrangements are traditional in colour and form, the plot involves all sections of a rapidly urbanising society, observed from a personal viewpoint, and sketched with the irony of the caricaturist.

Act One: Mersin

Theatrical idiom is apposite for describing Abaç’s works. His father. Celal Bey, was an actor of Istanbul’s Darülbedayi or City Theatre, where he rubbed shoulders with Muhsin Ertuğrul, perhaps the most famous name in the history of the Turkish stage. When Celal Bey moved to Mersin with his family, with a view to setting up a new theatre, the nine year-old Nuri rolled up his sleeves to brighten the sets. And so began a 70-year affinity with paint.

“Painting is to be found in a person’s genes; it does not develop later,” Abaç believes. “We bring it with us when we are born, and improve it in the course of time.” If he is right, this may explain why he turned an early hand to decoration and drawing rather than to acting. An early lesson came when the governor of Mersin, Tevfik Sırrı Gür, invited artist Nurettin Güven to paint pictures for some of the city’s buildings. While assisting Güven, Abaç realised that “Painting cannot exist – will go nowhere – without technique.”

Cartoon-time

“If I were a theatre actor, I would prefer comedy”, declares Abaç. Nevertheless, it was a long time before he achieved the light-hearted style which has been his trade mark for the past thirty years.

The cartoonist in Abaç came to the fore during his high school years, when he drew many cartoons for the magazine Akbaba (Vulture). He had returned to Istanbul, and was now able to make money from cartoons. But all of a sudden he realised how similar his drawings are to those of the best-known cartoonist of the day, Ramiz Gökçe. In response, he decided to give up drawing cartoons and began to paint again.

Drifting between styles

Abaç’s enthusiasm for painting was fuelled by a gift from Kemal Zeren, a relative and a teacher at the Fine Arts Academy, who left him all his paints, brushes and easels. For a year he attended the Leopold Levy Workshop of the Painting Department of the Academy as an occasional student. Then, at the insistence of his family, he switched to the Architecture Department, from which he graduated in 1950.

Of his initial, impressionist paintings, he can today locate only two: one which he entrusted to his aunt, and another which he still keeps at home. Another 30 or 40 paintings he simply gave away to his friends. Then came the abstract phase. He still loves abstract work, but adds that the field of abstract compositions is so vast, it would take more than a life-time to appreciate them all. As a result, one has to be selective. From the mid-1950s onwards, Abaç drifted in the direction of surrealism. In 1960, he moved to Ankara. And at a time when non-figurative painting was dominant, he became a rare protagonist of figurative expression.

Arriving in Ankara

During those early years in Ankara, Abaç developed a new of his own, informed by the belief that the path to the universal passes through the national and the local. His works of this period reflect the influence of Anatolian mythology, Hittite reliefs and Seljuk and Ottoman miniatures. In these canvases, which the artist now describes as “dark compositions”, one is struck by the emphasis placed on the instinct to voice feelings and, especially, fears – on the drive to convert terrors into screams.

Those paintings are coveted items today but were little in demand at the time. This Abaç opts to attribute to the relative scarcity of artistic activity even in Turkey’s larger cities at the time. All that was to change from the 1970s onwards. “The number of galleries has increased and interest in painting has increased enormously,” Abaç notes, “Just think, during the 1960s, there was no gallery in Ankara, and I had to open my exhibition at the lobby of a hotel in Sıhhiye.”

Before long the “dark” years would be over, and the artist would merge all his influences and experiences into the bright compositions for which he is justifiably popular today.

Mersin to Monaco

Since opening his first exhibition at the Halkevi (People’s House) in Mersin in 1949, Nuri Abaç has held more than 50 personal exhibitions in Turkey. His works were included in the exhibitions of the State Painting and Sculpture Museum from 1958 to 1991, and in all of the exhibitions of the United Painters and Sculptors Association, which was established in 1969, with Abaç as a founder member. In addition to exhibitions organised in other countries by the Turkish Foreign Ministry, he has been represented in over 120 exhibitions organized by various institutions and private galleries. His paintings have been displayed twice at both the Venice and Monaco Biennials. In 1988 he received his “Fifty-Year Art Award”. Today, he continues his efforts to bring his extraordinary fairy tales to life.

Pamukkale: Reviving the spa spirit

Whole cities have grown up in the past around the curative springs and streams of the Pamukkale region in Southwest Turkey. The region is now turning into a resort offering much to see and do in addition to the beauty spot from which it takes its name.

Everybody has heard of Pamukkale. For decades now, the extraordinary terraced hillside of cascading rock and welling water has been a sine qua non of Turkish tourism brochures. To busy residents and spoilt-for-choice holiday-makers, the familiar frozen image of white and blue, warmed by the heartthrob of thermal springs, may seem a little remote. But those who hesitate to visit the “Cotton Castle” are missing out on more than just one natural wonder.

Still white – and red

A decade ago, the landmark travertines showed signs of turning grey. This national disaster was swiftly averted. Gone are the hotels and hamams which had occupied the vital river valley and monopolised the hot water. And since 1997, visitors shod and unshod have been barred from wandering over the terraces at will and splashing freely in and out of the curvy pools (Alternative facilities are provided on site).

Thus at the expense of a little fun now, the delicate balance of geology, temperature and meteorology has been restored for the future: the calcium bicarbonate precipitates and hardens, and the whole faintly radioactive formation is regenerated, a milky white, ad infinitum.

Pamukkale is not the only hot or warm spring in the region and not all of them are white. Karahayit, five kilometres away, runs red with iron minerals, spouting a surreal miniature landscape of rainbow rock. Stalactites and stalagmites await visitors to the caves of Kaklık and Keloğlan and the nearby hills and forests conceal lakes like Saklı Göl, Işıklı Göl and Salda Gölü, waterfalls like Yeşildere and the bird reserve of Acı Göl.

Two cities

While nature has persevered on this spot for thousands of years, the human civilisations whose needs it has provided have come and gone. Adjacent to Pamukkale stand the dusty ruins of Hierapolis. Established in 190BC by the King of Pergamon and named after his Amazon queen spouse Hiera, the city was devastated by an earthquake in 60AD. It survived to become an important centre of early Christianity. The remains of gates, arcades, walls, temples, churches and a theatre are easily identified, and smaller relics are exhibited in the pleasant local museum, located in a Roman bath. Even so, the city is best known for the limestone and marble monuments of its extensive necropolis.

Compare and contrast the less spectacular hill-top ruins of Laodikeia, situated just a few kilometres to the south, and closer to the booming textile town of Denizli. These include two theatres, a stadium, a gymnasium, a council building, a monumental fountain and portions of giant aqueducts as well as a large church. A settlement from prehistoric times onwards, Laodikeia (or Laodicea) became one of the seven churches of Asia (Minor) of early Christianity (The Book of Revelations lambasts its cosy wealth and implicitly its tepid water).

How to spa

People have been “taken the waters” here for millenia. Ancient myths celebrate the beautifying properties of the thermal springs. In Roman times, religious ceremonies and festivals were held beside the pools. Wealthy individuals and statesmen apparently came to Hierapolis for healing, which was administered by priests and physicians. These were the precursors of the “health tourists” and “spa hotels” which are reinvigorating the Pamukkale region today.

Among the hotels of all sizes and grades at Pamukkale and Karahayıt are several which take the wellness concept seriously and offer a wide range of treatments and therapies as well as recreational activities and access to the timeless tonic springs. They seek to alleviate cardiac conditions, physiological complaints, skin diseases, all forms of aches and pains, digestive problems and loss of appetite, not to mention mere age or stress.

The Colossae package

One of the region’s leading facilities is the five-star Collossae Hotel, named after the third of the ancient cities of the Lycus River area, and pictured with this article. The hotel claims to be the only one with both Pamukkale and Karahayıt waters on stream. Aside from a choice of Turkish, sauna, thermal and herbal baths, three, five and seven-day “Collife” programmes can be booked which incorporate a range of massage treatment, hydrotherapy, electrotherapy, mud therapy and exercise. Personal programmes are suggested for slimming, beauty or combating stress.

There are indoor and outdoor swimming pools, a fitness centre and facilities for soccer, basketball, volleyball, tennis, squash and table tennis. Players, joggers and trekkers do not retain the smell of sweat for long in these aromatic surroundings. It is not always easy to choose between the balcony plus 24-hour room service and the indoor and outdoor restaurants and bars, with discos or live music.

New meeting point

Pamukkale has generally been a day-trip destination for holiday-makers to the Mediterranean and Aegean coasts. With all modern conveniences on hand, the itinerary can now be reversed, as early-rising travellers strike out from here towards Aphrodisias, Ephesus and the Aegean to the West, or Dalaman and Marmaris to the south.

The region’s hotels are also well-suited for private celebrations, retreats and conferences. The Colossae offers meeting rooms seating anything from 25 to 250 people, and banqueting for groups of almost all sizes. In short, you can still make excuses for not going to Pamukkale, but you can make many more excuses for going.

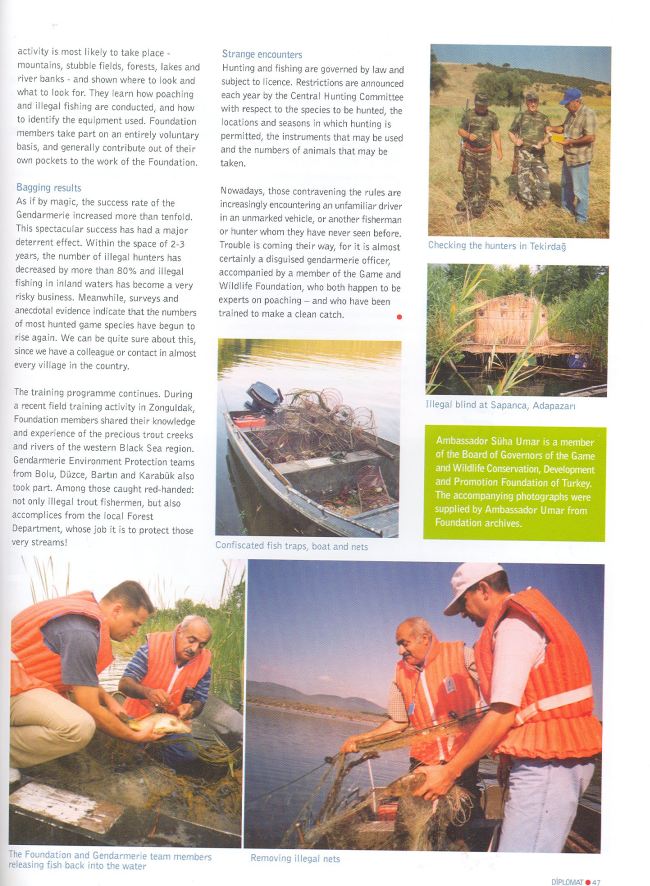

Environment teams: Trapping the poachers

by Süha UMAR (*)

Some 70% of Europe’s mammals, birds and plants can be found in Turkey. But conservation has not always been the country’s strong point. A number of the country’s diplomats are among those actively struggling to protect the rich natural heritage. One of these is Foreign Ministry Director General of Bilateral Political Relations Süha Umar. Here he explains the efforts which the fourteen year-old Game and Wildlife Conservation, Development and Promotion Foundation of Turkey has been making in conjunction with the Gendarmerie to counter illegal hunting and fishing.

Back in 1999 we were desperate. The populations of bears, deer, rabbits, wildcats and many other species were diminishing rapidly. Poaching and illegal fishing were widespread, and neither the then Ministry of Forestry nor the Ministry of Agriculture and Village Affairs were willing to do their duty and stop it. For all its valiant efforts, the Game and Wildlife Conservation, Development and Promotion Foundation of Turkey was unable to counter the threat alone. So we decided to talk to General Rasim Betir, Commander in Chief of the Gendarmerie.

General Betir was quick to grasp the situation and instructed two close aides to do everything to help us. Jointly, we launched a large-scale campaign against illegal fishing and hunting. First results were encouraging but these early achievements still needed to be consolidated. The next step was to be taken, in response to our discreet prodding, by another Gendarmerie Commander-in-Chief, General M. Şener Eruygur.

Imagine my excitement when I received the following message from friend and close collaborator Staff Colonel Metin Coşkun in 2002: “Keep it to yourself for the time being… but we will soon be setting up Gendarmerie Environment Protection Teams and Nature Conservation Units. These will be solely responsible for nature conservation and the prevention of poaching and illegal fishing”.

Training mission

The decision filled an important vacuum for specialized units. The next job was to train them. The first field training exercise took place in the mountains around Çatak, in Van, in October 2002. Within two days, around 40 poachers and five illegal fishermen were apprehended and brought to justice. Among them were members of the Police Special Forces.

Since then the Foundation has field-trained about 40 teams from Van and Bitlis in the East to Çanakkale and Tekirdağ in the West. The teams are taken to areas where illegal activity is most likely to take place – mountains, stubble fields, forests, lakes and river banks – and shown where to look and what to look for. They learn how poaching and illegal fishing are conducted, and how to identify the equipment used. Foundation members take part on an entirely voluntary basis, and generally contribute out of their own pockets to the work of the Foundation.

Bagging results

As if by magic, the success rate of the Gendarmerie increased more than tenfold. This spectacular success has had a major deterrent effect. Within the space of 2-3 years, the number of illegal hunters has decreased by more than 80% and illegal fishing in inland waters has become a very risky business. Meanwhile, surveys and anecdotal evidence indicate that the numbers of most hunted game species have begun to rise again. We can be quite sure about this, since we have a colleague or contact in almost every village in the country.

The training programme continues. During a recent field training activity in Zonguldak, Foundation members shared their knowledge and experience of the precious trout creeks and rivers of the western Black Sea region. Gendarmerie Environment Protection teams from Bolu, Düzce, Bartın and Karabük also took part. Among those caught red-handed: not only illegal trout fishermen, but also accomplices from the local Forest Department, whose job it is to protect those very streams!

Strange encounters

Hunting and fishing are governed by law and subject to licence. Restrictions are announced each year by the Central Hunting Committee with respect to the species to be hunted, the locations and seasons in which hunting is permitted, the instruments that may be used and the numbers of animals that may be taken.

Nowadays, those contravening the rules are increasingly encountering an unfamiliar driver in an unmarked vehicle, or another fisherman or hunter whom they have never seen before. Trouble is coming their way, for it is almost certainly a disguised gendarmerie officer, accompanied by a member of the Game and Wildlife Foundation, who both happen to be experts on poaching – and who have been trained to make a clean catch.

(*) Ambassador Süha Umar is a member of the Board of Governors of the Game and Wildlife Conservation, Development and Promotion Foundation of Turkey.

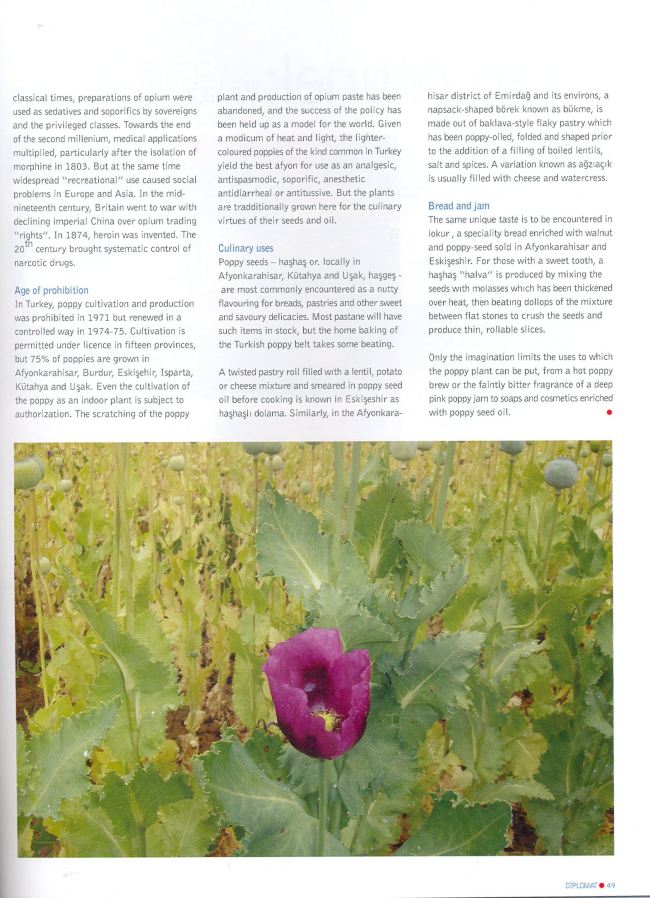

Poppies: A sight to savour

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

A feast for the eye – and indeed for the stomach – awaits visitors to a swathe of provinces in western Anatolia. This is the ancestral home of the delightful opium poppy, grown here not for the ambiguous pharmaceutical properties of its pod but for the wholesome nourishment of its seeds.

Crimpled crepe petals – bright red or patchy white, pink and magenta – fussing around bright contrasting organs above serrated fingery foliage. A single flower on a proud upright stem up to 1.5m high. Neither a giant of nature nor a dwarf, yet instantly recognisable as papaver somniferum – the opium poppy. An annual plant of delicate beauty which has forged enormous strategic, sociological and medicinal upheavals over the centuries. And nowhere more at home than in Turkey, where whole fields in bloom continue to offer a striking early summer spectacle.

The flower will make way for a bluish or greyish green capsule or pod. Scratched with a knife or needle at 1-3 weeks, the pod yields a milky substance which soon stiffens and hardens and can be processed further to obtain opiates like morphine – also the raw material for heroin – and codeine.

The poppy is considered to be native to Southeast Europe and Western Asia, from where its cultivation and use notoriously spread eastward with the assistance of Alexander the Great and later Arab traders. Today it is legally sown and harvested in several inland provinces of western Turkey – and above all in the province of Afyonkarahisar, which takes the afyon in its name from the Turkish word for opium.

From Hittites to heroin

The language of the Sumerians suggests that the poppy plant was known as long ago as 5000BC. From the second century BC onwards, the plant is said to have been traded by Egyptians and the sea peoples of Cyprus. On display at Afyonkarahisar Museum are stone reliefs and even coins bearing illustrations of the poppy, allegedly remaining from the time of the Hittites.

Poppy cultivation was first described by botanic pioneer Theophrastus (372-287 BC). In classical times, preparations of opium were used as sedatives and soporifics by sovereigns and the privileged classes. Towards the end of the second millenium, medical applications multiplied, particularly after the isolation of morphine in 1803. But at the same time widespread “recreational” use caused social problems in Europe and Asia. In the mid-nineteenth century, Britain went to war with declining imperial China over opium trading “rights”. In 1874, heroin was invented. The 20th century brought systematic control of narcotic drugs.

Age of prohibition

In Turkey, poppy cultivation and production was prohibited in 1971 but renewed in a controlled way in 1974-75. Cultivation is permitted under licence in fifteen provinces, but 75% of poppies are grown in Afyonkarahisar, Burdur, Eskişehir, Isparta, Kütahya and Uşak. Even the cultivation of the poppy as an indoor plant is subject to authorization. The scratching of the poppy plant and production of opium paste has been abandoned, and the success of the policy has been held up as a model for the world.