Project Description

16. Sayı

Observer

DİPLOMAT – ŞUBAT 2006

16. Sayı

Diplomat

Şubat 2006

The cold winter has been making life difficult for everybody in Turkey recently. But this is a country where all four seasons can be lived out to the full. By the time the nex edition of DİPLOMAT appears Spring will have arrived, and the snow and ice will be all but forgotten.

In the present edition of DİPLOMAT we have two important guests. Our interview is with Latvia’s dynamic ambassador to Ankara, Ivars Pundurs. Ambassador Pundurs has been making every effort to make his charming Baltic homeland betetr known in Turke. Besides increasing our knowledge of Latvia, he discusses frankly the problems it has faced and teh progress it has made since its rebirth in 1991.

On our “Speaking Out” pages, meanwhile, Turkmenistan’s ambassador to Ankara, Nurberdi Amanmuradov, explains his country’s policy of neutrality. Turkmenistan’s rich natural resources make it one of the most important countries of Central Asia. It is also of particular interest to Turkey for linguistic and cultural reasons. Ambassador Amanmuradov sheds light on his country’s relations with its neighbours and underlines the role played by the principles of President Saparmurat Niyzaov in the formation of foreign policy.

Famous both for his landscape paintings and his non-figurative abstract works, artist Lütfü Günay is one of the doyens of the Turkish art world. His scenes of Çanakkale, the province in which he was born, are particularly treasured by galleries and collectors. The life and works of Günay form the subject of our Arts pages this month.

Our travel pages, meanwhile, spirit you off to Portugal, the most Western country in Europe, and one of the most attractive. For those who are not in a position to cross the whole of Europe from East to West, we also recommend a visit to Mudurnu, which is just 200km from Ankara, and which together with nearby Lake Abant makes a fascinating and beatiful weekend outing at any time of year.

Among other articles which we believe you will find interesting, DİPLOMAT’s legal columnists Murat Demir and İbrahim Yüce turn their attention to the question of foreigners’ residence in Turkey, the procedures which must be followed and the rights which foreigners posses. We expect this information will prove useful for many of our readers.

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current opinion

Tunis, Turkey and the information society

by Fikret N. Üçcan

In 1995, a study carried out in the Unıted States comparing the multiplier effects of the information technology and manufacturing sectors revealed that each new job at Microsoft, as a software producer, created 6.7 new jobs in Washington state, whereas a job at Boeing created 3.8 jobs. Ten years later, nobody is in any doubt about the close link between information technology (IT) and the generation of wealth. As the World Development Report put it in 1999, “For countries in the vanguard of the world economy, the balance between knowledge and resources has shifted so far towards the former that knowledge has become perhaps the most important factor determining the standard of living – more than land, than tools, than labour. Today’s most technologically advanced economies are truly knowledge-based.”

IT enables change. It does not by itself create transformations in society, but acts as a tool for releasing the creative potential of people and facilitating knowledge creation in an innovative society. At the same time, IT is instrumental in opening up new markets and in fostering the vision of perfect competition, maximising growth potential. Knowledge spreads very quickly. Products with a high knowledge component generate higher returns. Competition goes hand in hand with innovation. To compete, any firm of any size must develop its capacity to innovate more quickly than its competitors.

Global marketplace

By allowing creative potential to surface, spreading knowledge and supporting competition, IT offers an opportunity to break down inequalities within and between societies. Another aspect of this opportunity is related to the globalisation of capital. With the help of IT, capital now circulates with the speed of light, regardless of geography, in search of the new investment opportunities which offer the best returns. Distance no longer determines the delivery time or the cost of communications.

Meanwhile, businesses can deliver their products down a telephone line anywhere in the world, twenty-four hours a day. In particular, software, one of the pructs with the highest value added, can be delivered anywhere at any time. In the resulting global market place, consumers are overwhelmed by choice: choice not only of products and services or of financial and intellectual capital, but also of ways and means to govern their futures and their childrens’ futures. These new trends normally lead people to demand more democracy and greater respect for human rights along with the ability to access the wealth generated by the knowledge economy.

Against this backdrop, the “digital divide” between those societies where the use of IT products and services is widespread and those where it is not can be regarded as a waste of the limited material, administrative and intellectual resources of the “information have-nots”. Wasted opportunities and effort prevent them from building a strategic and inspired future, which in turn leads to further shortages of human capital and and lack of knowledge-driven production. However, this is not a destiny which cannot be undone.

The WSIS process

Issues such as the above have inspired all countries to participate enthusiastically in the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) process, embarked upon by the United Nations and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) in Geneva in December 2003. The second phase of the WSIS convened in Tunis on November 16-18, 2005. The summit was extremely well organised, and according to our hosts over 20,000 people representing governments, international organisations, the private sector and civil society were present. There was an atmosphere of general conviviality, despite extremely strict safety measures.

As expected, the issue of the Governance of the Internet prompted lively discussion right from day one of the conference. Eventually a compromise was found to the apparent satisfaction of all parties. The US will retain, for an undetermined period, control of the Los Angeles-based Internet Corporation for Assigned Numbers and Names (INCANN). However, the Americans agreed that more representatives from other countries should participate in the management of the INCANN. It was also decided to create an Internet Governance Forum, for multi-stakeholder dialogue, to seek the best means of reducing the technological gap between rich and poor countries and to consider how to oppose the damaging invasion of spam, fight cybercrime and respect privacy and freedom of expression.

The issue of transforming the digital divide into digital opportunities for the developing world stemped its mark on the Tunis summit. The Digital Solidarity Fund, which was created to complement existing mechanisms for funding the Information Society, has been functioning for several months now. According to ITU officials, substantial progress was expected on this issue. When one bears in mind that two billion people have never had a ‘phone call in their lives – and that many more have never boarded an aeroplane or even heard about the Internet – the dream of an Information Society requires more than the embrace of a vision by world leaders. It requires money. And this can not come about unless rich countries decide to be more generous and to provide the Fund with the means to carry out its mission.

Turkey’s IT policy

Turkey was represented at the WSIS Summit in Tunis in November by a strong delegation headed by Mr. Binali Yıldırım, Minister of Transport and Communications. In his statement, the Minister made clear that Turkey considered the implementation and follow-up of the Tunis Agenda, as well as the commitments made by the international community during the two phases of the WSIS process, to constitute “the most crucial aspects of our common future.” He also invited the WSIS participants to attend the ITU Plenipotentiary Conference, to be held in Antalya in November 2006.

“Particularly in recent years,” Minister Yıldırım told the Summit, “Turkey has increased her efforts to manage the process of transforming Turkish society in a more coordinated manner. In this connection, a myriad of programs have been developed; namely, e-Government services in education, health, taxation, social security, the justice system and similar fields, broadband access to schools and infrastructure services to SMEs. Universal service regulations are being utilised to overcome the digital divide and projects are being developed to achieve social inclusion of those with low incomes, putting special emphasis on rural areas.”

Historically, Turkey’s Information Society policy emerged in the early 2000s with the creation of a Working Team at the Prime Ministry. In December 2003, in a move intended to ensure effective political leadership and government-private sector-civil society coordination, Information Society policy development was entrusted to the e-Turkey Executive Board, headed by Deputy Prime Mınister Dr. Abdüllatif Şener. Minister of Trasport and Communications Mr. Binali Yıldırım, Minister of Industry and Trade Mr. Ali Coşkun, State Planning Organisation (SPO) Undersecretary Dr. Ahmet Tıktık and Mr. Fikret Üçcan, Senior Advisor to the Prime Minister, also sit on the Board. Participants in Board meetings include representatives of the Scientific and Technical Research Council of Turkey (TÜBITAK), the Unıon of Chambers (TOBB), the Telecommunications Authority (TK) and relevant private sector organisations and NGOs. The SPO provides secretariat facilities.

Achievements and constraints

An international consultancy firm was subsequently commissioned to design a new Information Society strategy while a second group undertook the task of establishing a single online Portal to improve and simplify interaction between citizens and the administration.

Human capital, as the cornerstone of the Information Society, has been given special emphasis in the overall strategy. The initiative known as the Basic Education Project demands significant changes in the technological and human resources of schools: primary and secondary school classrooms are being endowed with computers with broadband connections, and teachers are attending specific training courses.

The e-Economy is a two-speed reality in Turkey. Some business sectors are driving fast towards the Information Society while others, especially most SMEs, are more reluctant to adhere to new e-business practices. The main constraints facing these smaller businesses are lack of skills and the legal and bureaucratic burden. To overcome this problem, the Government is trying to develop a legal framework in which e-Businesses will be stimulated and e-Business practices will be adopted by SMEs. The use of e-Signatures has been introduced to ensure the reliability and security of e-Business.

To sum up, Turkey’s path to the Information Society has been marked by a continuous effort to keep up with the agenda of the European Union at the same time as addressing the problems of its socio-economic structure. Many key actions have been taken in pursuit of greater competitiveness and growth in an innovative environment to better the quality of life in Turkey. However, Low IT skills and low ICT penetration in households and businesses still pose a major challenge to the dvelopment of a competitive knowledge-based economy in Turkey.

About the author

We are grateful to Mr Fikret N. Üçcan, Senior Advisor to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and former Prime Ministry Undersecretary, for contributing this month’s ‘Current Opinion’. Mr Üçcan entered the Turkish Foreign Ministry in 1964 after graduating from the Faculty of Political Sciences of Ankara University, from which he was later to obtain a master’s degree. He served in the Turkish embassies in Vienna, Amman, London, Tripoli and Kuwait and as Consul General in Strasbourg. Besides his diplomatic career, he held posts as Advisor to the State Minister, General Director of Social Planning at the State Planning Organisation and Undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture before being appointed Prime Ministry Undersecretary. He obtained a masteris degree from the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Ankara’s Gazi University in 1992, specialising in the role of human capital in economic development. He is now Senior Advisor to the Prime Minister. His international career includes services as Deputy Chairman of the UN Population Commission, Deputy Chairman of the International Professional Training and Teaching Association (IVETA) and Chairman of the Eureka Audiovisual and European Audiovisual Observatory. His publications include ‘Önce İnsan’ (Human Being First) and ‘Kültür Mirasımız’ (Our Cultural Heritage), and translations into Turkish of “Management for the Future” by Peter Drucker, “Preparing for the 21st Century” by Paul Kennedy and “Chaos” by James Gleick.

Where WSIS goes next

by Bernard KENNEDY

February will see further steps towards enabling less developed countries and communities to grasp the opportunities offered by information technology, rather than being left behind once again as they were during the industrial revolution.

First, a date is expected to be set for the inaugural meeting of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), due to take place in Athens late this year, with about 1,000 participants. Greece offered to host the event during the second phase of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in Tunis in November last year.

Second, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), UNESCO and the UNDP are jointly organising a consultation meeting of WSIS Action Line Moderators/Facilitators in Geneva. The meeting will help to allocate responsibilities for implementing the “action lines” set out during phase one of the WSIS in Geneva in December 2003. These include: the role of public governance in promoting the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for development; information and communication infrastructure; access to information; applications such as e-government and e-health; cultural diversity; media, and ethical aspects of the information society. A range of UN organisations are expected to become involved along with the ITU and other stakeholders.

Meanwhile, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan is due to report back to the UN General Assembly in June on progress made by the UN Group on the Information Society towards inter-institutional coordination and implementation of WSIS results. The Assembly is later expected to confirm May 17 as Information Society World Day and to initiate a “Tunis+10” event in 2015 to examine how far the WSIS conclusions have been implemented.

All of these developments follow the adoption at Tunis of the ‘Tunis Commitment’ and ‘Tunis Agenda for the Information Society’.

Inclusive information

The Commitment reaffirms the determination of the participants to “build a people-centred, inclusive and development-oriented Information Society… so that people everywhere can create, access, utilise and share information and knowledge, to achieve their full potential and to attain the internationally-agreed development goals and objectives…” It stresses the need for better access to technology and infrastructure, training and security, and touches on issues as cultural diversity, the role of the media, the abuse of the Internet, the use of technology in small businesses and the possibility of using debt relief to enable developing countries to increase their ICT efforts. It calls for “universal, ubiquitous, equitable and affordable access to ICTs” for all people including women, children, youth, the disabled and other marginalised or disadvantaged groups, peoples and countries.

The ‘Tunis Agenda’ seeks to put some flesh on this declaration of intent by setting out the next steps in the WSIS process, including the thorny issues of financing and internet governance which were carried over from Geneva to Tunis. Bridging the digital divide, it says, will require “adequate and sustainable investments in ICT infrastructure and services, and capacity building, and transfer of technology over many years to come” – and this cannot be left simply to market forces. It encourages development assistance, technology transfer, favourable investment climates, the free participation of developing countries in world markets for ICT-enabled services, and a stronger focus on ICT from donors and multilateral institutions.

The Agenda welcomes the establishment, at Geneva, of the ‘Digital Solidarity Fund’ (DSF), a Swiss Law foundation financed initially by contributions totalling some USD6m from 20 founding states, local governments, and international agencies. The City of Geneva has initiated a scheme whereby public ICT procurement contract-winners make a 1% contribution to the Fund. The DSF is currently financing projects in Africa involving Internet access for HIV/AIDS-threatened communities and distance education for healthcare centre personnel.

Running the Internet

International management of the Internet, the Agenda states, should be “multilateral, transparent and democratic, with the full involvement of governments, the private sector, civil society and international organisations. It should ensure an equitable distribution of resources, facilitate access for all and ensure a stable and secure functioning of the Internet, taking into account multilingualism.” The Agenda speaks of the need to develop a culture of security and to combat cyber-crime, spam and terrorism while respecting rights to privacy and freedom of expression. It calls for measures to uphold consumer rights and extend e-government applications. It argues for low international interconnection costs, multilingualism and software “that renders itself easily to localisation, and enables users to choose appropriate solutions from different software models including open-source, free and proprietary software”.

The Agenda goes on to ask the UN Secretary-General to set up the IGF, detailing its tasks and responsibilities. At the same time, however, it recognises that “the existing arrangements for Internet governance have worked effectively to make the Internet the highly robust, dynamic and geographically diverse medium that it is today, with the private sector taking the lead in day-to-day operations, and with innovation and value creation at the edges.” The IGF is to have “no oversight function and would not replace existing arrangements, mechanisms, institutions or organisations, but would involve them and take advantage of their expertise. It would be constituted as a neutral, non-duplicative and non-binding process. It would have no involvement in day-to-day or technical operations of the Internet.”

Tunisian connections

Tunis was an appropriate venue for phase two of the WSIS, since it was the Government of Tunisia that first proposed the holding of such a summit at the ITU Conference in Minneapolis in 1998. The ITU won UN executive support and its plan for a two-phase event was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2001. Both the Geneva and Tunis phases were attended by heads of state and government or vice-presidents from close to 50 countries. In all, ministers and other top officials from175 countries took part, alongside representatives of international organisations, the private sector and civil society.

Active Internet policies have made Tunisia one of the best-connected among African and Arab countries. The Summit built on its experience in this field as well as its key location between North and South. The DSF is reminiscent of Tunisia’s own National Solidarity Fund for social solidarity and of the World Solidarity Fund which it successfully proposed to the UN General Assembly in 2002. President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali has devoted much of his time to extending the use of ICTs and narrowing the digital divide.

Interview

Ambassador Ivars Pundurs: How Latvia took its chance

He is one of the longest-serving ambassadors to Ankara, yet his Embassy was opened less than a year ago. The answer to this riddle is Latvian envoy Ivars Pundurs, who became accredited to Turkey as non-resident ambassador in 2001 but continued to serve as undersecretary for security policy and international organisations at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Riga until the Embassy on Reşit Galip Caddesi went action at the beginning of 2005. In this interview, Ambassador Pundurs draws attention to some interesting aspects of his country’s relations with Turkey and speaks frankly about a range of other issues ranging from his countries membership of the EU, NATO and the Iraq coalition to the Latvianisation drive ties with Russia.

Q Yours must be one of the newest foreign embassies in Ankara?

A Yes. After Latvia became independent in 1919 there were diplomatic relations between Latvia and Turkey but there were no embassies. President Vaira Vike-Freiberga opened the Embassy officially during her official visit last April, and late last year Turkey appointed its first resident ambassador to Riga.

I must add that many countries never recognised the Soviet annexation of the Baltic states, and in fact Turkey was one of them. This is something that we are very grateful for: it was important for us to know that there were friendly countries in the West who believed like us that Latvia could one day be independent again.

Q Are there any other historical precedents for relations between the two countries?

A One living memory of the Turks in Latvia is from the Ottoman-Russia war in the 19th century, when Turkish prisoners of war were transported to Latvia. There is a well-kept cemetery of Turkish soldiers in a town in Central Latvia called Cesis. There is also a village – which is actually on the way between Riga and my parents’ home – called Turki, meaning “Turks” in Latvian. This name dates back to the same period.

Q What do Latvians know about Turkey and vice-versa?

A Turkey has been the number one travel destination for our holiday-makers for the past two years. Around 30,000 people a year visit Turkey from Latvia. Since March last year, our national airline Air Baltic has had direct flights to Istanbul and Turkish Airlines will also start operating to Riga soon. One of the largest residential real estate projects in Riga is being carried out by the Turkish company MESA.

In Turkey, I think we became much better known after our soccer team beat Turkey on aggregate for the ticket to the Euro 2004 finals in Portugal! We always seem to be paired together in sporting competitions. Latvian and Turkish women basketball teams met in the Women Eurobasket 2005 tournament in Ankara last September and in a fierce contest the Latvians won 81-78. One of our leading basketball players, Kaspars Kambala, plays for Fenerbahce. In 2003, the year when Turkey won the Eurovision Song Contest, the contest was staged in Riga.

Q What is the Embassy working on at the moment?

A On February 19-22, we are expecting a visit from the speaker of the Latvian Parliament, Ms Ingride Udre. We expect this will kick off some cooperation at the parliamentary level. Meanwhile, we are seeking to ease visa requirements. A draft agreement is under discussion and I am confident that we will be able to make travel easier for Latvian and Turkish citizens visiting their respective countries.

On the cultural and social side, there is a non-government organisation here in Turkey called TELLFA – the Turkish-Estonian-Latvian Lithuanian Friendship Association. We are trying to enable Turkish people to study Latvian in the University of Latvia. There are plans to hold Turkish days in Riga, Vilnius and Tallinn, and Latvian and Lithuanian and Estonian days here in Turkey.

Q What would you like the rest of the world to know about Latvia?

A The slogan that we have adopted most of all is “the land that sings”. It is no coincidence that we have won the Eurovision song contest. Latvian conductor Mr Mariss Jansons has just won a Grammy award for the best orchestral performance, conducting Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Latvian opera singer Ms. Elina Granca was also nominated for a Grammy this year for her part in a recording of Vivaldi’s ‘Bajazet’. We have a very rich folk culture. Besides music, there are artists of many kinds. In terms of nature, it’s a very green country. In terms of people it is a multicultural, multi-religious society. Riga is an interesting Hansiatic, northern city with a very nice atmosphere: in the era between the two wars it used to be known as the “little Paris”.

Q What about the economy?

A After the Soviet period, of course, we had to re-orient our economy from the East to the West. For the past 3-4 years it has been growing by about 10% per annum. The figures for 2005 are not yet known but in 2004 we were the fastest-growing economy in Europe. We have become more services-oriented. Riga is becoming a financial centre for the Baltics and a “crossroads” for trade in goods and energy resources between the Russian Federation and the West. We have the advantage of a very developed road, rail and pipeline infrastructure, and our ports are ice-free in winter.

We have a history of food-processing. Between the wars, we used to export cheese to the Netherlands! We are now cooperating with Turkish producers. In Soviet times we had a strong electronic goods industry. Many people in places like Turkey still have radio receivers produced in Riga. Now there are new companies and products – such as micro-wave transmitters.

Q How has EU membership changed Latvia?

A I think what changed Latvia most was not EU membership as such but the path to EU membership. Our economic growth has mainly been a result of the reforms which we carried out in order to adopt the acquis. If you look at the countries of Eastern and Central Europe and compare those which have been aspiring to EU membership with the others, there is a tremendous difference.

It is fantastic that we are where we are now. History presented us with an opportunity and we made use of it. It has been difficult but it has been worth it.

Q What were the most difficult parts of the accession process?

A EU membership doesn’t come free of charge. While the country altogether is clearly a winner, some groups have to pay a price. In our case, most of the political debate centred on agriculture and fisheries. The environment too is a very expensive chapter [of the acquis]. We have many transition periods. We have a saying in Latvia that “Riga is never built”. In other words, nothing is ever completely finished.

We had to work hard to bring our administrative capacity up to the necessary level. This may be easier in the case of Turkey, but in Latvia, we had to tackle the same number of issues as the larger EU membership candidates with a much smaller bureaucracy.

Q What is the state of Latvia’s relations with Russia?

A Latvians have strong memories of the 50 years of forced cohabitation, when we were part of the same country, dominated by Russia against our will. Many in Russia have a different view of that period. Because of this common history, we have difficulty resolving some issues. We do not have a formal signed and ratified border agreement. Even so, relations have come a long way since 1993-1994 when we negotiated the Russian troop withdrawal. Economic ties are developing and as time goes by I think we will come to some common view of historical issues, or at least they will cease to be such an obstacle.

Q Have you had any problems over gas supply or pricing?

A No. Like all Russia’s neighbours, we are dependent on Russian natural gas. The recent dispute between Russia and Ukraine has sparked a debate in Latvia, as elsewhere, about the need to diversify supply. But our cooperation has been on a commercial basis and we have not had any shortage of supplies. In fact, the Russians have a stake in our domestic natural gas company, together with the German company Ruhrgas. In addition, we have a large underground storage capacity which is used by the Russians to store gas in the summer for use in the St Petersburg area in the winter.

Q What progress has been made on resolving the status of the Russian minority?

A Before World War II, Latvians made up more than 70% of the population. But by the last Soviet census, due to conscious Soviet policies, the figure was only slightly over 50%. Moreover, the language of interethnic communications, as they called it, was Russian. Latvian went out of use in certain areas. You could read Russian newspapers, watch Russian TV and use Russian at the workplace. So by 1991 we had some features of two communities existing in parallel. In response, we established Latvian as the state language and offered language courses to those who wanted to learn. Fifteen years back you would frequently enter a shop in Riga and start speaking in Latvian and the shopkeeper would say “Sorry, I don’t understand. Could you speak Russian?” You cannot imagine this happening now.

People are free to speak whatever language they choose in their private life and in business. We don’t regulate the private sphere. To give an example of the tolerant, multi-ethnic nature of our society, we have minority schools in nine languages. But in the same way as the state language is Turkish in Turkey, so the state language in Latvia is Latvian. We are a multicultural society but not a segregated society. There are no districts inhabited only by Russians, Ukrainians or Belarussians. There are no businesses that are just for, say, Latvians.

Q What about the citizenship aspect?

A Parliament decided that people who were citizens of Latvia in 1940 and their children would get citizenship automatically. For others we offered the opportunity to obtain citizenship through naturalisation. As a requirement, we introduced a simple Latvian history and language exam. Language is an important concrete element of social integration. How can you make people full-fledged members of the society if they don’t understand your language?

Many countries accept a certain number of immigrants, in an orderly fashion, which gives them time to develop policies to try to integrate them into their societies. In our case, substantial immigration occurred which was beyond our control. For the time being I would claim that we got it right. We have had no inter-ethnic violence whatsoever.

We now have less than 20% of non-citizens. Our membership in the EU has also been a major catalyst for increasing the number of applications for Latvian citizenship. On the other hand, those who do not apply for citizenship enjoy all the same rights except that they do not vote. For example, we offer the same consular protection and assistance here in Turkey both to these permanent residents and to our citizens.

Q Do the Baltic states form a kind of bloc or do they have differences?

A We would look at these countries as our closest allies and friends. We are all different, but our friendship goes back a long way. We were united in our struggle for independence and have shared the same foreign policy and security goals, including membership of the EU and NATO, which we all joined at the same time. From the early 1990s we established an institutional structure for Baltic cooperation, perhaps influenced a little by the Benelux model. There is a Baltic assembly which is a parliamentary forum of the three Baltic states and there is also a Baltic Council of Ministers and working groups in almost all of the areas of government. We had free trade in agricultural products among ourselves long before we joined the EU. Within the EU and NATO, I wouldn’t say we operate as a bloc but we cooperate.

Q Was joining NATO inevitable or could Latvia have stayed neutral?

A We joined NATO just a few weeks before the EU. All along we had even greater public support for NATO membership than we had for EU membership. Between the two world wars we were neutral. We lost our independence in 1940 as a result of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany. Nobody came to help us. So the main lesson we drew from this was that never again would we want to be left alone if anything went wrong. So there was really no doubt about joining NATO.

This doesn’t mean that we see any country in the neighbourhood as a threat. Of course the world has changed a lot since 1940. But wherever the threats may come from, a small country cannot go it alone. No country in the world can really go it alone.

Q What is the thinking behind Latvia’s participation in the Iraq coalition?

A First of all, we have lived under authoritarian rule ourselves, and knowing that the people of Iraq lived under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein – and of the atrocities which the regime had committed against the people – we thought maybe we should be among those who would do something about it. Secondly, we honestly thought at that time that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. Thirdly, although it was not a NATO mission, it was led by the USA which is also our leading ally in NATO. Among allies the level of trust is different than simply among friendly countries. In a way we are repaying some debt to the international community for what it has helped us to achieve. This also helps to explain why we are in Afghanistan.

In terms of pure national interest and security policy, too, it’s clear that the threats are now coming from the “Greater Middle East”, so we want to play our part in this region. Whatever the debates about the necessity of armed intervention in Iraq, the coalition will clearly have to stay there for some time to come to make sure that when the Iraqis are left alone they will be capable of keeping peace and order and ensuring the development of their country. And the same is true for Afghanistan.

We have slightly over 100 troops in Iraq. We are pulling our weight considering the size of our population. I must admit that society at large is not overenthusiastic about our involvement. We have lost one soldier in Iraq.

Q On a more personal note, how do you find living in Ankara?

A Ankara is a convenient place to live. Professionally it’s very interesting: there is a very strong diplomatic corps here. Istanbul is an amazing city. But personally, I would prefer to live in Ankara and go to Istanbul for the weekend than vice-versa. Istanbul is four times the size of my country in terms of population and I have spent many hours in the traffic jam just waiting to cross the bridge. I try to travel around a lot. I am also taking my photography more seriously. There is a lot to be photographed here.

Human angle

Turkey, Armenian allegations and the West

by Prof. Dr. Özer OZANKAYA

Over the past 40 years, many Western governments have held the Turkish nation and the Turkish Republic responsible for the bloody Armenian-Turkish conflicts which were incited, particularly by Russia, Britain, France and America, in the East and South Anatolian regions during the final years of the Ottoman State. Further, they have concurred in the presentation of these events as a “genocide carried out by the Turks against the Armenians”. Ignoring the requirements of objectivity and consistency, they have approved parliamentary resolutions to this effect, and even enacted laws punishing those who do not defend this position! Together with the Armenian government, these Western states close their ears to Turkey’s appeals for proposals to examine the issue in a scientific atmosphere according to objective criteria.

Objectivity is the leading requirement of international peace and democracy. It is also one of the foundations of the Turkish Republic. As Atatürk warned, “Writing history is just as important as making history. If the writer is not loyal to the history-maker, then the unchangeable truth turns into something surprising for humanity.” With respect to the Armenian genocide allegations, a significant number of French scientists last month stressed that it was wrong for the French Parliament to convert its political views on historical issues into laws and resolutions, and argued that writing history should be left to researchers. This statement is pleasing. As a sociologist, I would like to add my own observations and remarks on the issue – not as rigid assertions, but as suggestions which are open to criticism.

History written and rewritten

The destruction of the Ottoman State was accompanied by much suffering on the part of Ottoman nationals as a result of conflicts of interest among the industrialised Western states in their search for natural resources and markets. The greatest anguish was experienced by the Turkish section of society, which had borne most of the burden of the Ottoman State, but been left out of all progress.

As America’s Professor Justin McCarthy sets out in his research on migration in the region, Ottomans of Turkish origin were cast out of homes which they had occupied in Rumelia (Southeast Europe) for 500 years. Similarly, an attempt was made to form a region deprived of Turkish population in the East, in order artificially to create an Armenia. Armenian gangs, set up and armed with the support of the British, Russians and French, launched an initiative to massacre Turks, including women, the elderly and children, and to force them to flee the region. The majority of the Armenian population could not or did not rebel against these murders. However, although attacks on Turks were successful in the western provinces of the Ottoman State, they did not succeed in the East. The Ottoman State obliged the population of Armenian origin in this region – and this region only – to migrate southward, in order to protect the Turkish population and prevent them from being stabbed in the back while fighting against Russia.

During the War of Independence, Armenians in French military uniform were used to attack Turks in Adana, Maraş and Gaziantep. This made it even more impossible for the Armenians who had been subject to deportation to return to their homelands upon the foundation of the Republic. In short, the Armenian people in Eastern Anatolia lost their opportunity to live in peace together with their Turkish neighbors because they could not or did not refuse to serve as a vehicle for the interests of the Western states. They had been present in the region for over a thousand years. They ended their existence in the region by their own hand.

As of the 1990s, Armenian politicians backed by the political West began to turn the incidents upside down. Making no mention of the attacks on the Turks, they let it be known that the Ottoman State and Turkish nation had carried out a genocide against the Armenians, just as others had sought to annihilate the Jews. The Republic of Turkey had attached great importance to preventing the past from poisoning the present, and chosen not to put the responsibility of the political West for the painful incidents mentioned above onto the international agenda. But this noble policy was regarded as an indication of weakness and used against Turkey as a weapon.

Points to consider

Slandering a nation is itself a kind of genocide attempt. The inaccuracy of the propaganda has been proven many times. Some of the convincing arguments used to debunk the smear campaign are as follows:

- The Ottoman State drifted into World War I as a result of the efforts of Enver Pasha and similar state administrators under the control of Germany. The whole Ottoman Army was under the direct command of the German generals who constituted the “German Military Training Council”. Liman von Sanders and Falkenhein are the best-known examples. If the Ottoman State were to commit genocide against Armenian nationals, the German government would have ample opportunity to document it. But no such document has been found in the German archives.

- The Ottoman State, which signed the Mondros Ceasefire Agreement, surrendered the entire administration to the British, French and Italian occupiers. The war criminals were delivered to the courts and exiled to Malta. However, although the states which had won the war seized all the archives of the Ottoman state, they found no proof to indicate that genocide had been implemented against the Armenians, and they were able to make no such allegation. If any proof had been found in the British, French, Russian and Italian archives up until now, it would have been declared to the whole world many times over.

- During the period of the Ceasefire and the Turkish War of Independence, the American administration assigned General Mosley and General Harbord to research the Armenian allegations. They stated that there had been no genocide – only “mutual killings” – and noted that Turks had suffered the greater losses during the clashes. They did not pass judgement as to who started the killings: had it been the Turks, one doubts whether they would have remained silent.

- Prior to the 1877 Ottoman-Russian War, Britain, on account of its own colonialist interests, was opposed to any attack to be launched by Russia on the Ottoman State on the pretext of protecting the Armenians from oppression. Britain assigned a Royalty captain to observe the situation on the spot. According to Captain Peebody’s report, ‘Five Hundred Miles on Horseback in Asia Minor’, the Armenians were not subject to pressure. Indeed, he found them to be the most prosperous and richest section of society. However he noted that they might not be entirely loyal to the Ottoman State.

- We know that the Armenians attacked their Turkish neighbors in French uniforms in the Adana-Maraş region. Subsequently, French Prime Minister Clemenceau did not refrain from arguing that the Armenians had nobody to blame but themselves.

- The allegations of Armenian genocide were never voiced during the time of Atatürk. Turkey received a special invitation to join the League of Nations, and not a word was said about the allegations.

- Had the Armenians been subjected to genocide in Turkey, the hundreds of Jews who escaped from Nazi Germany, like the German scientists, artists and intellectuals who revolted against the regime, would not have wanted to live in Atatürk’s Turkey rather than the US, Switzerland or Canada. They would not have felt that they could live in a fully free atmosphere in Turkey.

- The Ottoman state had regarded the Armenians as its ‘Teb’a-i sadıka’ – or most loyal citizens. For many generations, the palace architects (such as the Balyan family) had been chosen from among the Armenians, and Armenians had been appointed to the highest official positions. The Armenians had become very close to the Turks in every aspect of culture. They printed books in Turkish using the Armenian alphabet and widely spoke Turkish even in their homes.

- Even today, Armenians living in many countries throughout the world frequently speak Turkish in their homes and among themselves. If they had been obliged to emigrate due to genocide in Anatolia, which was their homeland for thousands of years, they would scarcely want to continue speaking Turkish.

Turkish “encouragement”?

The best strategy which any nation can follow is to possess a contemporary culture. A democratic administration, freedom in philosophy, science and arts, an economy based on advanced industry and technology, and a developed written language provide a nation with the greatest possible security. However, following World War II, Turkish politicians failed to pursue the enlightening revolutions which Atatürk had begun. They sought easy ways of staying in power and served selfish interests, leaving the vast rural population largely uneducated, and weakening the Republic. In these circumstances, the political West, which has yet to condemn colonialism, renewed its attacks on the Turkish Republic and the Turkish nation, so as to prevent the Atatürk model from becoming an example for the Islamic world and the exploited nations, and to reduce Turkey to the level of a colony once again. This was done sometimes under the guide of assistance; sometimes with the aid of ignorant and/or self-seeking writers and academics, Turkish or foreign. The Armenian genocide allegations have to be seen in this context.

In order to end the Armenian slanders and prevent their use as blackmail for the achievement of political and economic goals vis-a-vis Turkey, Turkish governments must express the above-mentioned facts with a loud voice, and make quite clear that the behaviour of governments which put this issue before their parliaments, raise it on international platforms or enact laws infringing the freedom of thought and forbidding any questioning of the genocide allegations will be regarded as hostile and will meet with an appropriate response.

At the same time, it follows from the above observation that Turkey needs strong, democratic governments conscious of their accountability to the nation. Officials outside and inside the country should be appointed not on partisan lines but among people who are capable of safeguarding the nation’s interests. And academics and intellectuals should lend their support within an understanding of democratic citizenship.

World view

Truth: the first casualty of World War I

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV

Truth is the first casualty of war! This is true for all wars, and it is exactly what happened in World War I as well. This war was the first global armed conflagration of deceitfulness, nourished by fiction, developed by ignorance, and sustained by prejudice. While smearing whole nations in the opposite camp, it sent millions of young persons to their death and laid the seeds of another world war even crueller than the first.

It was during the First World War that propaganda was recognized as a vehicle of control over the public mind. Propaganda was apotheosized as an effective weapon in warfare. The British Government was more successful in this endeavour than the others. It brought out so-called ‘Blue Books’ and other brainwashing publications in various rainbow colours, not to reveal the truth, but to persuade its own public and world opinion that the enemies of the Entente Powers were immoral, criminal and captive. Consequently, they themselves, who eventually emerged as the victors, represented the just, the good and the free.

A major aim was to persuade the neutrals, foremost among them the United States, to enter the war and help to defeat Germany and the Ottoman Empire. The public was persuaded to believe that the handouts revealed the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. In the event, nineteen countries declared war on Germany and its allies (including the Turks), and ten broke off relations with the opponents of the British. Propaganda induced much of the world to form a very adverse opinion of the Germans and the Turks.

Organising the show

These two belligerents, against whom the British and their allies fought in several fronts, were the main targets. The lies manufactured to degrade them were outrageous and disgusting. Governments, missionaries and individuals frequently put together fables and offered them to the news media. Warmakers, especially the British leadership, which developed the art of propaganda, presumed that cover-ups, distortions, fabrications, mistranslations, omissions and outright lies would weaken the enemy, make friendly support more powerful and allure the neutrals to the desired cause, no matter how confusing it might have become in the process.

The falsifiers did not care at all if their enemies, including their whole peoples, were irresponsibly and systematically degraded. While these were dragged to the level of indisputable criminals, the propaganda drive led to more and more conscriptions. One inevitable result of the whole scheme was that not all conscripts came back home alive.

- L. George, who eventually became Prime Minister (1916-22), was the first politician to suggest, in his then capacity as Cabinet member, the idea of an official propaganda campaign. His pressure resulted in the establishment of the Wellington House network. It was, however, H.H. Asquith, Premier until 1916, who actually called on C. F.G. Masterman, a well-known publicist, to set up a propaganda bureau. The latter’s War Propaganda Bureau at Wellington House worked in secrecy, free even of parliamentary scrutiny. With an initial staff of 54, it became, within a short time, the most sizable and effective organisation involved in the formulation, editing, printing and dissemination of propaganda. Soon, a new section dealing with the Muslim countries was created. It eventually reached a swollen staff of 300.

Multi-media campaign

Wellington House was the largest but not the only propaganda establishment. Rivalry developed among various government departments and groups, trying to outbid the other.

The principal means of propaganda was the pamphlet, written by well-known authors in high literary quality or academic in tone. Masterman’s first report in mid-1915 showed that 2.5 million copies of propaganda material, printed in seventeen languages, had already been circulated. In his second report, in early 1916, the figure had reached seven million copies. Two ‘Blue Books’, one aiming at the Germans and the other at the Turks, were sizable compilations that slandered, smudged and vilified the leading enemies.

To serve this general purpose, selected functionaries were made responsible for dailies, periodicals, official guests, the elite or the general public. Personnel sent to foreign capitals were under strict orders not to disclose their connections with the British Government. The Foreign Office tried to impress and persuade the American news media and the decision-makers in that country above all. Four châteaux were financed for the use of the foreign journalists. Wellington House or Reuters, the leading British news agency at the time, opened up offices in several European cities to place articles in the papers there. Some foreign papers were directly financed from the Treasury. Artists were commissioned to draw pictures for propaganda purposes. Blueprints were composed on the basis of rumours as well as sketches of the fronts. Ninety British artists, including then the famous Muirhead Bone, drew war paintings. Masterman also set up a Cinema Committee to reach directly the eyes and ears of the average member of the public.

Smoke-screen

Much of the published material was sent to the United States, which the British wanted to push into active belligerency, and to India, where the Muslims especially were sympathetic towards the Turks, but which happened to be the “most precious jewel” in the British crown. Wellington House saw to it that their material appeared in foreign media and was read in public places – even in barber shops. The curtain that hid all these activities was so thick and all-embracing that it led to criticisms that the government was doing nothing as propaganda. In fact, just the reverse was true.

The British presented its case in an entirely one-sided manner. It did not allow the views of its adversaries to be heard. To this end, the British concealed some facts and distorted others. The main motive was to present the British side as virtuous, and the enemy as barbarous. This was supposed to be a requirement of patriotism. Even legally speaking, moreover, the Defence of the Realm Act (1914) forbade the printing of information directly or indirectly useful to the enemy. All doors were closed to German and Turkish views, and even to balanced and truthful information that in a way honoured the enemy. The whole idea, instead, was to arouse public opinion in a chosen direction.

This strategy became a vital weapon in the war. The dramatic increase in casualties prompted the British Government to insist on this kind of distortion even more. Deliberate official imbalance, and even lying, was unsurpassed in the whole history of the world. The reverse side of the medallion was the tremendous injustice done to the Germans and the Turks.

The atrocity line

It was also a denial of truth, at least the whole truth. The government never allowed the virtues of the enemy to be mentioned. The other side of the coin was not disclosed. The propaganda covered up retreats, magnified successes, and above all disseminated news about “atrocities” – a concept calculated to pump hatred into the minds of the people. The distorted record in relation to Germany was later corrected. The truth about the Turks during the First World War, and about their relations with the Armenians, still needs to be presented in a balanced manner. The required fair-mindedness is still lacking in the policies and the practices of a number of governments and their peoples.

A summary of what these distorted images were, in respect to the Germans and Turks, and why they were unreliable, must be left for a future article.

Speaking Out

Ambassador N. Amanmuradov: Active neutrality

Rich in natural resources, Turkmenistan is approaching the 15th anniversary of its independence, surrounded by major powers and trouble-spots. Turkmenistan’s Ambassador to Ankara, Nurberdi Amanmuradov, is a former lecturer in agricultural engineering who rose through the Central Youth Committee of Turkmenistan during the tumultuous years of 1990-1992. After studying at the Diplomatic Academy in Moscow, he headed the Consular and Pacific departments of the nascent Turkmen Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He represented his country in various capacities in Istanbul and Ankara for over eight years before being named ambassador in 2004. Here, he describes the special relationship between the two countries, and outlines Ashgabat’s policy of active neutrality.

Relations between Turkmenistan and Turkey have made a rapid start to 2006. Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Hilmi Güler was in Ashgabad between January 19 and January 21, laying the foundation of a new iron and steel plant. Meanwhile a seven-man technical team from Turkmenistan has been examining Turkey’s dams and irrigation techniques (As you know, water is like gold in our country). Last year was also a busy year: several Turkish ministers travelled to Turkmenistan and a delegation from the Turkmenistan Democratic Party visited Ankara in November.

All of this is quite normal. We are two states but one nation, sharing language, religion and culture. Since Turkmenistan gained its independence on October 27, 1991, almost all of the construction works have been carried out by Turkish contractors. About 200 Turkish companies are operating in Turkmenistan, mainly in construction, textiles and food. About 12,000 Turkish people work in Turkmenistan, and 1,200 Turkmen students are pursuing graduate and postgraduate studies here. Cooperation continues in agriculture and livestock, and regular mutual visits take place under the auspices of Turkey’s development agency TICA.

With the backing of TICA and the ministries of Foreign Affairs and Culture, paintings by Mr Owezmuhammet Mammetnurov of Turkmenistan and Mrs Hatice Kumbaracı Gürsöz of Turkey were exhibited at the State Painting and Sculpture Museum in Ankara in May of last year, in an exhibition symbolising the friendship between the two countries. In August, the Turkmen National Youth Theatre ‘Alparslan’ won an award at the International Istanbul Theatre Festival.

While there is still much potential to be realized, the fruitful course of bilateral relations is well known. Therefore, I would like to take this opportunity to reflect on Turkmenistan’s international relations in general and especially on our policy of neutrality, the tenth anniversary of which we have just celebrated.

History of neutrality

On December 12, 1995, the General Assembly of the United Nations issued a resolution concerning the permanent neutrality of Turkmenistan. This date is now Turkmenistan’s second most important public holiday. In fact the foreign policy of Turkmenistan was formally born at the Helsinki Summit of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1992. It was here that President Saparmurat Niyazov (Turkmenbashi) for the first time declared the principle of positive neutrality.

The principle of neutrality includes respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of other nations, non-interference in their internal affairs, the non-use of force in interstate relations, and the priority of UN decisions. Turkmens attach special importance to their neighbours and Turkmenistan has trade and cultural relations with all neighbouring countries. It has peaceful ties with all countries. It is recognised by 125 states and is a member of more than 40 international organisations.

In 1994 the President had meetings and conversations with the heads of state of China, France, Turkey and Pakistan. All expressed complete support for the policy of positive neutrality. The neutrality of Turkmenistan gained international recognition at the third summit of the members of the Economic Cooperation Organisation (ECO), held in Islamabad in 1995. Later in the same year, Turkmenistan became the 114th full member of the Non-Alignment at its Cartagena ( Colombia) summit.

Finally on December, 27, 1995, the Halk Maslahaty Turkmenistan, the supreme representative body of people’s power, assembled and affixed the neutrality of Turkmenistan into the country’s constitution and laws. The principle gives Turkmenistan a legal and moral right to offer itself as a place for settling regional conflicts. It was Ashgabat which initiated negotiations between contending Afghan factions, which was an important contribution to the overall efforts of the international community aimed at stabilisation in the region. In 1996 our capital hosted several rounds of inter-Tajik negotiations that helped find a political solution to the civil conflict in Tajikistan.

Afghanistan and beyond

Turkmenistan has become a key country in rendering assistance to Afghanistan and rebuilding the social infrastructure. For three years, Turkmenistan has been delivering electricity cheaply to northern Afghanistan. It also provides health treatment for Afghans who are ill. In 2002, Ashgabat granted a quota for the education of Afghan students in Turkmen universities and institutes, free of charge, so that they could learn vital professions such as agricultural engineering. About half of the aid being provided by international organizations is transported through Turkmen territory.

Turkmenistan is neutral and its territory cannot be used for transporting armed forces or military cargo. However, Turkmenistan permitted its airspace to be used by aircraft of the Anti-Terror Coalition Forces transporting humanitarian aid to Afghanistan.

In 2002, President Niyazov proposed the establishment of a Central Asian Consultative Centre for resolving problems amicably at the level of heads of state. The initiative was to include Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan as well as the former Soviet republics. All these countries face issues like the threat of terrorism, drug-trafficking and transnational organised crime.

In his article “Strategic partnership in the name of ideals of peace and humanism”, which was recently published in the ‘UN Chronicle’ magazine, President Niyazov insisted that Turkmenistan’s neutrality was “not a shell to protect us from threats and troubles” but “a strong position to actively influence the situation in the region and in the world… to promote effective international cooperation, which is an important factor of internal economic development… There is an urgent demand of life to build bridges of cooperation wherever is possible and not to create barriers between countries.”

Sustainable development

Turkmenistan takes part in the initiatives of the UN Regional Disarmament Centre for Asia and the Pacific. In September 1996, it signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty and in 1997 it supported and became a co-sponsor of the UN General Assembly resolution on the establishment of a nuclear weapons-free zone in Central Asia. In October 2003, the first round of the Forum on Conflict Prevention and Sustainable Development for Central Asia was held in Ashgabad under the auspices of the United Nations and the OSCE. Turkmenistan has proposed to host a new UN Centre for Preventive Diplomacy in Central Asia. It has also offered to provide economic assistance to UN agencies opening headquarters on its territory.

Investment in Turkmenistan in sectors such as infrastructure, energy, textiles, health and education has reached US$7bn in the past 14 years. Over the same period, per capita income has risen from US$7 to US$7,500. The economy is guided by the “Strategy of economic, political and cultural development of Turkmenistan until 1920”, implemented thanks to the efforts of President Niyazov. The population has been provided with free electricity, gas, water, salt, education and medical services. Citizens are exempt from most taxes.

Gas strategy

It is the wish of the President that Turkmenistan’s natural resources should be shared with the world. Turkmenistan’s gas strategy is objective, without any artificial politicisation. Multiple pipelines will connect states and catalyse cooperation on other issues. Producer, transit and consumer countries must all benefit. For example, the trans-Afghan pipeline, designed to transport gas to Pakistan and India, will generate much-needed jobs and revenues for Afghanistan. Moscow is now ready to participate in such projects, rather than simply blocking the export of Turkmen gas by any route except the northern route, for the sake of stability and its own economic benefit.

In a sense, we are shifting away from unilateral control over the sources of raw materials and the means of their delivery to a multilateral model. This will avert the threat of clashes between major powers and at the same time permit regional nations to play the active role to which they aspire, realising their potential independently and becoming equal partners in world affairs.

Celebrating Flag Day

February 19th is National Flag Day in Turkmenistan and also the birthday of President Saparmurat Niyazov. The development of national symbols was part of the “return to the Turkmen essence” which preceded the President’s “Great Transition” policies. The flag code was signed by the president on February 19, 1991. The colour green, which forms the flag’s background, occupied an important place in ancient Turkmen society, symbolising life, activity, holiness, and continuity. The traditional Turkmen carpet motifs represent the magic of tradition, while the New Moon symbol reflects not only the Turkmen belief on the continuity of life, but also the expectation of a brighter future. The five-pointed star is a reference to the unity of the clans, the friendliness between regions and the five great periods of Turkmen history. Finally, the olive branch stands for the permanent neutrality of Turkmenistan, its peaceful approach to international relations and the hospitality of its people.

Portugal:

Europe at its most western

Europe is a small continent drawn closer together by history. At the far end of the land mass is a country with a distinct atmosphere of its own, as different as possible from Turkey, yet not without similarities. Steeped in the past, the Lisbon and Porto regions alone offer the visitor plenty to see, plenty to enjoy and plenty to go all the way back for.

What does Portugal remind you of? Mediterranean olive oil and wine? Or the surf of long, white, breezy Atlantic beaches? Catholic culture and traditional festivals – or contemporary football stars? Border castles and noble crafts – or the EU’s technology drive? Explorers in sailing ships – or a game of golf?

Everybody has their own point of view, and it can be surprising. In Turkey, Lisbon is often said to resemble Istanbul, with its wide expanse of water, its broad bridges, its trams, its seven hills, and narrow winding streets. The mouth of the Rio Tejo is said to recall the entrance to the Istanbul Straits – although the minarets, domes and palaces are here replaced by the very different silhouettes of the Belem tower, the Jeronimos Monastery, the monument to seaborne discoveries and the replica Christ-the-King statue from twin-town Rio de Janeiro.

In terms of population or of the pleasant coastal resorts which surround it, the Portuguese capital is more reminiscent, if anything, of a dramatically embellished Izmir. Yet only the most home-sick would dwell upon such matters amid the eclectic architecture and alluring shop windows of Europe’s most Western capital. This much perhaps may be said: both the diversity and the unity of the European heritage are as amply illustrated in its gateway to Latin America as they are in its bridge to Asia. The nearby Cabo de Roca is the most westerly point on the continental land mass.

Inside Lisbon

Lisbon lacks none of the monuments or public spaces which characterise Europe’s other historic cities. Churches, monasteries and other religious buildings abound – many would include Benfica’s ‘Estadio da Luz’ in the list. There are too many museums to mention from the National Museum of Antique Arts to the giant oceanarium on the Expo 98 site.

The city owes much of its special flavour to the broad avenues of the downtown Baixa district, where tourists assemble for pedestrian-friendly shopping by day and taverns and ‘fados’ by night. Cleared and rebuilt after the 1755 earthquake, the district offers a delightful foil to the medieval texture of the steep surrounding quarters, to which it is linked by the extraordinary 1902 Santa Justa “elevator”.

Other specialities include the pavements, designed and decorated as nowhere else, and the typical blue tiles which adorn the walls of pastry shops and mansion houses, inside and out, depicting above all the sailors and boats of Portugal’s golden age. These tiles can be photographed but not reproduced: souvenir-hunters must fall back on trade-mark ‘Vistalegre’ ceramics.

Seafood with everything

For gastronomists, Lisbon is difficult to beat. The surrounding countryside provides delicious goat and sheep cheeses and the world-famous Moscatel wine. Desserts include ‘Malveira’ pastries, ‘pao de lo’ sponge cakes, gin cakes (‘zimbros’), miniature cheesecakes (’queijadas’) and “Belem” custard tarts. Moscatel wine is made nearby. But the greatest delicacy of all is the seafood.

The Portuguese work wonders with cockles, muscles, clams and oysters, and make the most of sea bream, red mullet, sardines and swordfish. Fish is used in as many different ways as meat is used in Turkish cuisine. There are fish soups and fish pies. Fish are salted and desalted and served with just about everything. The staple diet – or almost – is the bulky Atlantic deep-sea ‘bacalhao’ or cod. There are said to be 365 ways of cooking cod, so that it can be eaten every day of the year.

Vegetables are generally served as side dishes, and the main dish of meat or fish tends to be accompanied by potatoes or rice. Agreeably, many eating houses serve much the same fare as you would find in every family home. There are also restaurants, needless to say, where the presentation is a great deal more sophisticated.

The world of port

Porto is a short hop from Lisbon by plane or a three-hour journey by car. If in a hurry, take the state-of-the-art tilt train from the equally state-of-the-art ‘Gare Oriente’. Thanks to its long and illustrious history, the whole of Portugal exudes nostalgia. But nowhere is this truer than in Porto, with its narrow alleys, its old harbour and its riverbank cellars, concentrated in the Gaia district, where the sweet fortified port wine is left to age before shipping.

The city’s major sights range from another twelfth century cathedral to nineteenth century monuments like the Sao Bento station and the spectacular two-tier iron bridge. Look out too for the sailing barges which have borne precious casks since time immemorial.

The mystic atmosphere continues inland, where the Rio Douro wanders calm as a lake among the vineyards where the port is conceived. The Douro is still used for commercial transport, as it has been for centuries. A leisurely trip up-river – at least a day trip – is a must, yet it is not without its dangers. For a tranquil afternoon on the water may tempt you to explore what lies beyond Portugal’s two famous cities – and further whet your appetite for a stay in one of its characteristic ‘solares’ or ‘pousadas’.

Homes from home

These away-from-it-all destinations are historic buildings, ancestral mansions, country houses and cottages used for high-end tourist accommodation by agreement with the families that own them. Often dating back to the 17th or 18th centuries, they provide holidays with a personal touch amid soothing natural settings, period furniture and elegant gardens. They exist everywhere on the mainland from the Costa Verde to the Algarve. They range from the majestic to the practical ‘casas rusticas’.

For those who take the time to explore, Portugal is a country too large to exhaust and yet small enough to become intimately acquainted with. Unsurprisingly, most tourists go back there again. The food, facilities and climate make the country ideal option for those with children. Everything is well sign-posted, getting around is easy and the people will make you welcome.

Take the usual precautions against pickpockets and crime. But do not be deterred by the news that Lisbon saw snow for the first time in 52 years last month, By the time you read this, the almond will be budding in the south and in the north the cherries will be about to burst into blossom.

Arts :

Lütfü Günay: The warmth of nature

by Sibel DORSAN

Based in Ankara for over 50 years, Lütfü Günay’s works express his deep love of the scenes and colours of Anatolia and his native Çanakkale. The veteran artist couples his affection for his subject matter with technical skills developed over years of painstaking training and experimentation. He has exhibited in several foreign countries, and has had a long connection with the United States through JUSMAT and the Turkish American Association.

Lütfü Günay speaks the honest, straightforward words of a sincere and unassuming man. It is his time-worn worker’s hands that do the talking. Though washed and washed again, the weathered skin retains within its crevices the tell-tale gleam of paint of every hue. “We are the hands of an Artist,” they seem to say, “We have been drawing and painting for almost sixty years.”

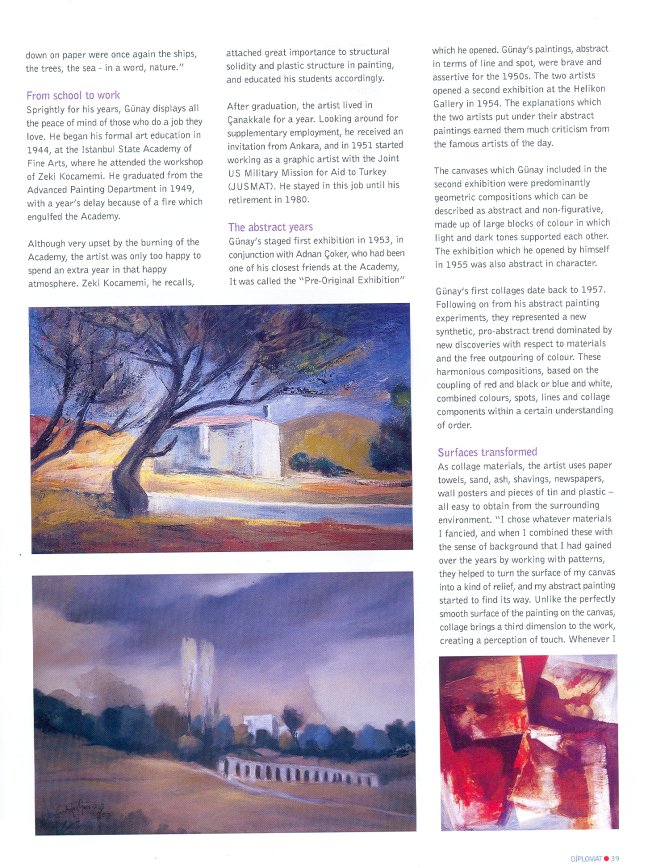

The canvases in Günay’s workshop tell their own story too. His deep love of nature is obvious in almost all of them. But most fascinating of all are his Çanakkale landscapes: paintings depicting the dark blue waters of the Dardanelles or the greenery of vineyards and olive groves.

Some of these canvases are boldly figurative, others more abstract. All have a warmth which embraces the spectator and draws him or her into the centre of the picture. They are inspired by the love of the artist for the region where he was born almost 82 years ago.

A Çanakkale childhood

“The landscape I was born into overlooked the Dardanelles from the best vantage point, full of greens and blues. The vineyards, the olive groves and the deep green atmosphere of Kilitbahir offered me an environment where I could live out my childhood and early youth freely – where I could be at one with the earth and discover nature at first hand.”

“When I was still only a little child, I used to make models of the ships passing through the Dardanelles, using mud which I mixed from the soil of our vineyard, a plot of sloping land looking out over the sea. Perhaps without being aware of it, I was inhaling and absorbing the colours of the sea, the sky and the olives. Later when I was old enough to hold a pencil, the things I jotted down on paper were once again the ships, the trees, the sea – in a word, nature.”

From school to work

Sprightly for his years, Günay displays all the peace of mind of those who do a job they love. He began his formal art education in 1944, at the Istanbul State Academy of Fine Arts, where he attended the workshop of Zeki Kocamemi. He graduated from the Advanced Painting Department in 1949, with a year’s delay because of a fire which engulfed the Academy.

Although very upset by the burning of the Academy, the artist was only too happy to spend an extra year in that happy atmosphere. Zeki Kocamemi, he recalls, attached great importance to structural solidity and plastic structure in painting, and educated his students accordingly.

After graduation, the artist lived in Çanakkale for a year. Looking around for supplementary employment, he received an invitation from Ankara, and in 1951 started working as a graphic artist with the Joint US Military Mission for Aid to Turkey (JUSMAT). He stayed in this job until his retirement in 1980.

The abstract years

Günay’s staged first exhibition in 1953, in conjunction with Adnan Çoker, who had been one of his closest friends at the Academy, It was called the “Pre-Original Exhibition” which he opened. Günay’s paintings, abstract in terms of line and spot, were brave and assertive for the 1950s. The two artists opened a second exhibition at the Helikon Gallery in 1954. The explanations which the two artists put under their abstract paintings earned them much criticism from the famous artists of the day.

The canvases which Günay included in the second exhibition were predominantly geometric compositions which can be described as abstract and non-figurative, made up of large blocks of colour in which light and dark tones supported each other. The exhibition which he opened by himself in 1955 was also abstract in character.

Günay’s first collages date back to 1957. Following on from his abstract painting experiments, they represented a new synthetic, pro-abstract trend dominated by new discoveries with respect to materials and the free outpouring of colour. These harmonious compositions, based on the coupling of red and black or blue and white, combined colours, spots, lines and collage components within a certain understanding of order.

Surfaces transformed

As collage materials, the artist uses paper towels, sand, ash, shavings, newspapers, wall posters and pieces of tin and plastic – all easy to obtain from the surrounding environment. “I chose whatever materials I fancied, and when I combined these with the sense of background that I had gained over the years by working with patterns, they helped to turn the surface of my canvas into a kind of relief, and my abstract painting started to find its way. Unlike the perfectly smooth surface of the painting on the canvas, collage brings a third dimension to the work, creating a perception of touch. Whenever I start to get bored with the smooth surfaces of figurative paintings of nature, I try to achieve the irregular surface that I desire in abstract collages.”

Landscape abstractions and figurative works started to appear in Günay’s exhibitions during the 1960s. In the 1970s, they came to take on more and more importance. It is supposed that his close friend, the famous painter Eşref Üren, had an influence over these figurative landscapes, based on his impressions of nature.

As a student at the Academy, Günay had had difficulty persuading his father about the wisdom of his choice of career. But when the old man, now living in İstanbul, visited an exhibition of his in the Göztepe district of the city in 1979, he was moved by the welcome that he and his son received, and turned to his son and said, “It’s a good thing that you became a painter”.

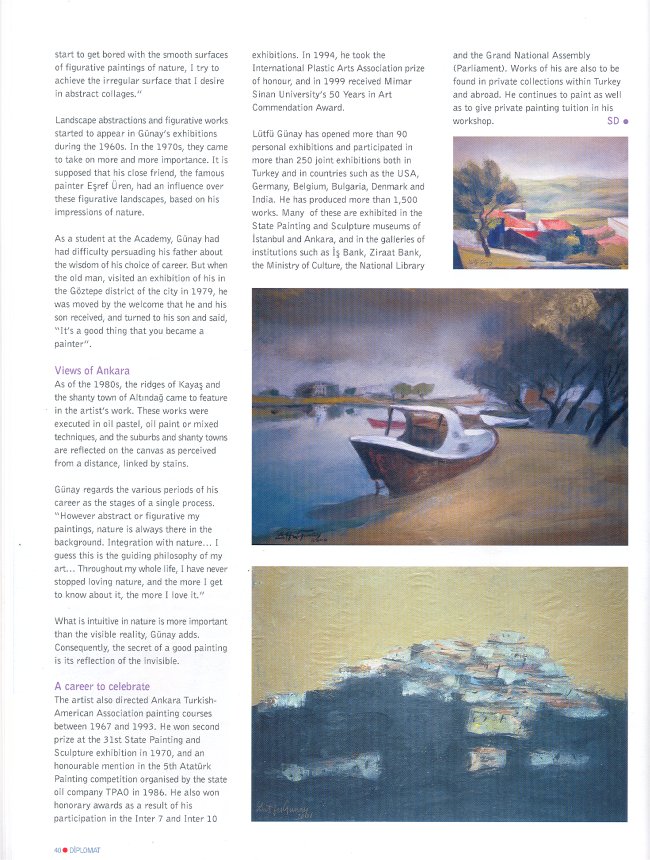

Views of Ankara

As of the 1980s, the ridges of Kayaş and the shanty town of Altındağ came to feature in the artist’s work. These works were executed in oil pastel, oil paint or mixed techniques, and the suburbs and shanty towns are reflected on the canvas as perceived from a distance, linked by stains.

Günay regards the various periods of his career as the stages of a single process. “However abstract or figurative my paintings, nature is always there in the background. Integration with nature… I guess this is the guiding philosophy of my art… Throughout my whole life, I have never stopped loving nature, and the more I get to know about it, the more I love it.”

What is intuitive in nature is more important than the visible reality, Günay adds. Consequently, the secret of a good painting is its reflection of the invisible.

A career to celebrate

The artist also directed Ankara Turkish-American Association painting courses between 1967 and 1993. He won second prize at the 31st State Painting and Sculpture exhibition in 1970, and an honourable mention in the 5th Atatürk Painting competition organised by the state oil company TPAO in 1986. He also won honorary awards as a result of his participation in the Inter 7 and Inter 10 exhibitions. In 1994, he took the International Plastic Arts Association prize of honour, and in 1999 received Mimar Sinan University’s 50 Years in Art Commendation Award.

Lütfü Günay has opened more than 90 personal exhibitions and participated in more than 250 joint exhibitions both in Turkey and in countries such as the USA, Germany, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark and India. He has produced more than 1,500 works. Many of these are exhibited in the State Painting and Sculpture museums of İstanbul and Ankara, and in the galleries of institutions such as İş Bank, Ziraat Bank, the Ministry of Culture, the National Library and the Grand National Assembly (Parliament). Works of his are also to be found in private collections within Turkey and abroad. He continues to paint as well as to give private painting tuition in his workshop.

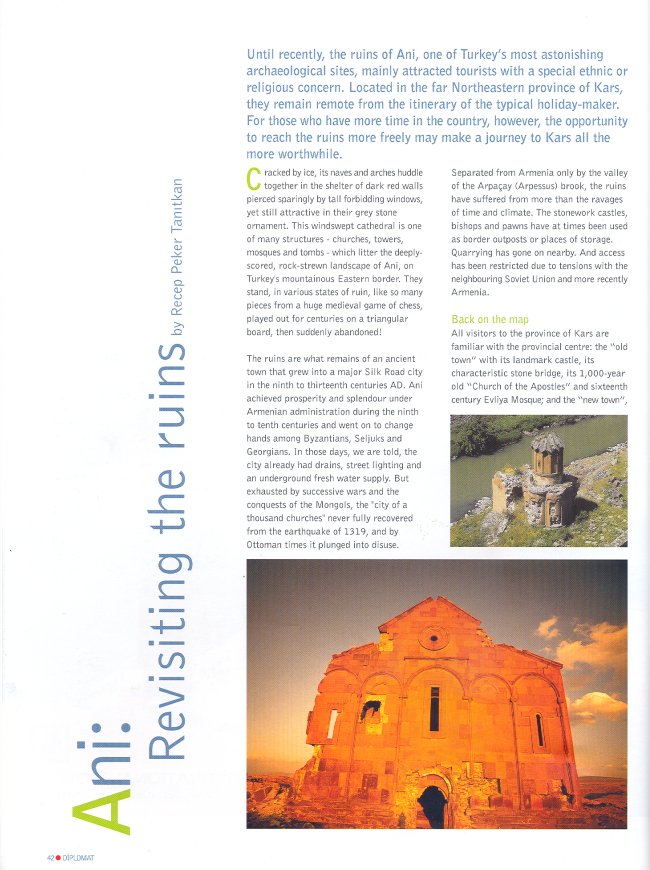

Ani : Revisiting the ruins

by Recep Peker Tanitkan