Project Description

4. Sayı

Past Times

DİPLOMAT – ŞUBAT 2005

4. Sayı

Diplomat

Şubat 2005

Every edition of DİPLOMAT contains fresh innovations.

With this February edition, we are proud to welcome a new columnist: Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV, one of Turkey’s leading academics in the field of international relations. For many embassies, Professor ATAÖV will already be a familiar figure. He has authored over 100 books – and more articles than he can remember – encompassing not only political issues but also cultural topics and the arts. Many of his books have been translated into foreign languages, and his works have been published in over twenty countries. Professor ATAÖV’s contributions will undoubtedly enrich the intellectual content of DİPLOMAT.

Our guests from the international and diplomatic community this month are Ambassador Sobizana MNGQİKANA of the Republic of South Africa and Edmond McLOUGHNEY, Representative in Turkey of the United Nations Children’s Fund. Ambassador Mngqikana expresses the views and concerns of the large African country which he represents, while Mr. McLoughney updates us on UNICEF’s current activities.

This issue also transports readers to Bucharest, where we report on a full-scale exhibit created by reconstructing houses from the various regions of Romania. We believe this unique ethnographic museum will capture every reader’s interest.

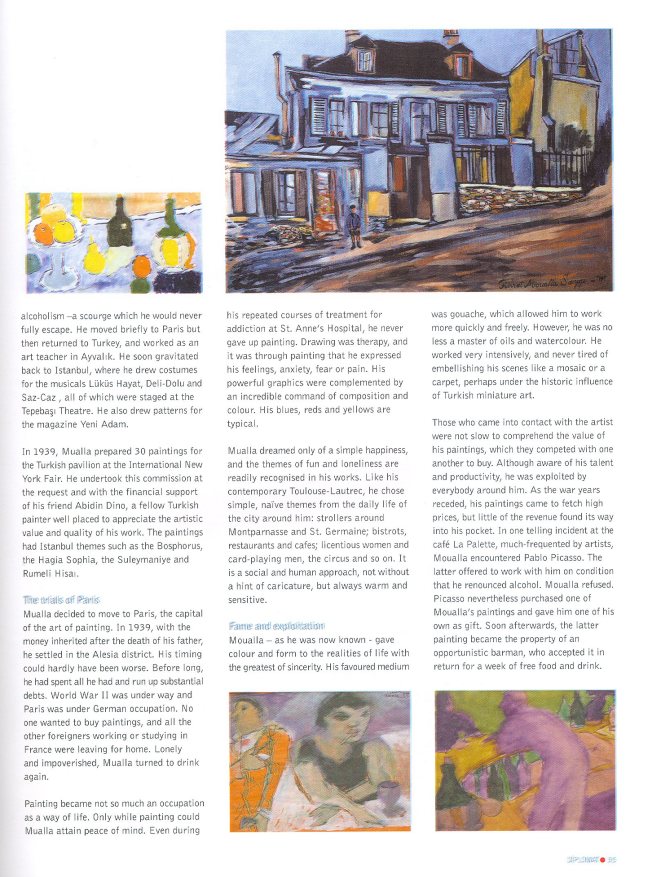

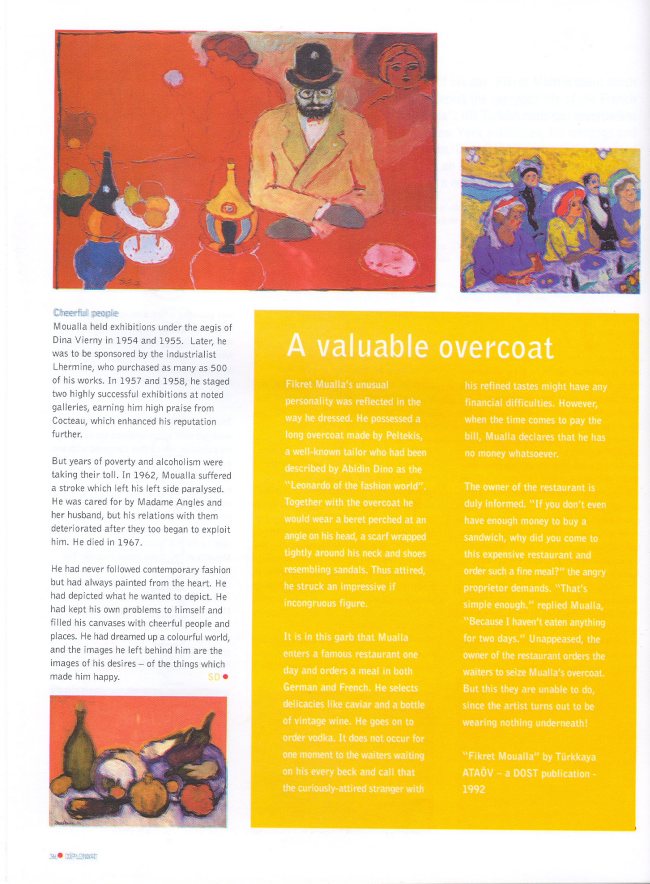

Our arts pages are devoted to the acclaimed twentieth-century Turkish painter Fikret Moualla. Moualla spent a large part of his life in Paris, which was also the city where he died. For this reason he is regarded as a French artist as well as Turkish one. Through painting, he sought to alleviate the harmful impact of his stormy life. He is considered one of the masters of expressionism.

The publication of DİPLOMAT this month coincides with Saint Valentine’s Day. If, as you read these lines, you have still not expressed your affection for the person you love – it’s time to get a move on…

Kaya Dorsan

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Current Opinion

Russia: Another Pole?

by Bernard KENNEDY

The exchanges between Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan and Russia’s President Putin have brought an “enhanced” if not “strategic” partnership onto the agenda.. Strong economic ties and a decline in tensions over political issues augur well for such a relationship. However, sections of public opinion on either side may still regard it as unnatural. Moreover, the role sought by Russia in Turkey – particularly in the energy sector – may contradict the visions of the US, IMF and EU.

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s trip to Moscow on January 10-12 has led Turkish commentators to take more seriously the “strategic relationship” proposed by the premier on the occasion of President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Ankara on December 5-6.

The Putin sortie was the highest-level visit from Moscow for more than three decades. Indeed, one Turkish business leader described Putin, with only a dash of hyperbole, as the most powerful Russian to visit Turkey in 512 years of diplomatic relations. The accords signed included a five-page partnership agreement aiming to raise the relationship between the two countries to the level of a “multi-dimensional enhanced partnership.”

All this was underplayed by the Turkish media, at the time entirely focused on the EU membership bid. Putin did succeed in dominating television news bulletins and holding up the Ankara traffic for a day or so. But the fanfares and security precautions were no match for those which surrounded President Bush’s stop-overs in both Ankara and Istanbul on the occasion of the NATO summit six months earlier. In the absence of any “concrete deals”, Erdogan’s proposal was politely dismissed as rhetoric.

Erdogan’s swift reciprocatory mission to Moscow, on the other hand, could not be ignored. It took place on a grand scale verging on grotesque. The premier was accompanied by at least a tenth of the Turkish parliament, five cabinet ministers and 500 entrepreneurs. Despite the long-standing political, cultural and money-laundering affiliations between Russia and Greek Cyprus, Putin deplored the unfair isolation of the Turkish Cypriot community. Erdogan opened a $60m Turkish shopping mall – only five minutes from the Kremlin, to cite the journalese – and proposed that a “Russian year” should be staged in Turkey and a “Turkish year” in Russia.

Economic foundations

The prospect of Moscow becoming a third strategic pole for Ankara, after the EU and Washington, is intriguing. The rapid growth of economic ties since the natural gas breakthrough of the 1980s is a matter of record. In the first eleven months of 2004 Turkey purchased US$7.8bn worth of goods from Russia – primarily gas and oil – accounting for 9% of its total import bill. Russia was Turkey’s second-largest supplier after Germany. For comparison, Turkey’s imports from the USA were put at only US$4.2bn. As a market for Turkey’s exports during the same period, Russia appeared to lag behind six EU member countries and the USA, purchasing only US$1.7bn worth of Turkish goods compared to US$4.4bn for the USA. However, the figure for exports to Russia excludes some US$3bn worth of informal “suitcase trade” sales.

In addition, 1.6m Russian tourists visited Turkey last year – again putting Russia in second place behind Germany, with almost a tenth of total arrivals. Russian tourists spent around US$1bn in Turkey. Turkish firms have invested an estimated US$12bn in Russia in breweries, factories, supermarkets, hotels and other enterprises. Not for nothing is US retail giant Wal-mart reportedly seeking a back-door entrance into Russia via the Koc Group’s Ramstore (Migros). Turkish building contractors, who earned Russian respect by sticking out the 1998 rouble crisis, are still undertaking billions of dollars’ worth of contracts in numerous cities. Arguably, the economies are complementary, with Turkey offering consumer goods and services and Russia natural resources, heavy industry and perhaps defence industry know-how.

Political improvements

There are firm enough foundations here on which to upgrade political ties. Political circumstances too may be conducive. The supposed animosities of the Cold War have faded. Moreover, some of the issues which emerged or re-emerged in its wake have de facto been resolved. It is clear that the Central Asian republics have remained broadly within Russia’s compass, and that Russia itself is a more important opportunity for Turkey than any of them. Moscow has had to come to terms with the Baku-Ceyhan oil pipeline, which will now be operable within months. Potential tensions over the volume of tanker traffic through the Bosphorus can be defused through the construction of a trans-Thrace or trans-Anatolia oil pipeline.

Given the US war on terrorism, the Istanbul bombings of 2002 and the Beslan incident, which caused Putin’s visit to Turkey to be postponed from the beginning of last September, Russia may be winning the ideological battle over the portrayal of Chechen nationalism. In the present circumstances and under the present government, Turkey cannot be expected to show the same tolerance towards Chechen militants as in years past. If this is the case, then counter-charges of Russian support for the Kurdish nationalist PKK will disappear of their own accord.

Converging on Iraq?

Instead of playing computer games involving the bombing of Libya, Iran and of course the USSR, tens of thousands of Turks are nowadays reading a cheap novel (Metal Firtina by Orkun Ucar & Burak Tuna, Timas publications) in which Turkey is bombed and invaded by the USA. This popular Turkish antipathy to US policy may have boosted Putin’s expectations of Ankara. There is a kind of convergence in the concerns of Moscow and Turkey concerning US foreign policy and its likely impact on their own interests. Russian strategists need allies and may see Turkey as a potential partner in regaining some influence in the Middle East. Turkey is trying to avoid becoming over-committed to the US – especially in military terms. Common calls for a greater role for international organisations serve as a starting point.

All this makes a strategic relationship possible but it does not make it a reality. In public opinion, the image of Russia as a centuries-old enemy of the Ottoman Empire persists at least to some extent. And while many Turks have heard of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky, very few read or listen to them, and it is not Russian serials and trade marks which appear on their TV screens at every hour of the day. A recent survey by a Turco-Russian research group indicated that the Russia was chiefly associated in the Turkish mind with prostitutes. Undoubtedly, the Russians have their own doubts and prejudices. At best, they regard Turkey as a shopping centre and playground; at worst as a potential source of Islamist threats.

Diverging on business?

In some respects, closer relations with Moscow need not upset the West. Neither Turco-Russian military exercises in the Black Sea nor a dialogue between Turkey and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation are likely to draw criticism. But Russian gas sales to Middle East countries via a partly Russian-constructed pipeline across Turkey to Ceylan on the Turkish Mediterranean coast could conflict with US-led plans for the region. And more generally, when it comes to doing business, the West will not want to be side-lined.

The seeds of today’s economic relationship with Russia were sown in the 1980s when Turkey started to buy natural gas, and Moscow earmarked business for designated Turkish contractors to help offset the cost. More complex barter arrangements now seem to be on the table, under which – for example – Turkey’s natural gas purchase commitments are reduced, and the re-sale of Russian natural gas to third countries is permitted, in return for Russian involvement in oil and gas pipeline construction, in gas storage facilities, trade and distribution, in electricity distribution and in oil refinery operation in Turkey.

Interview

Ambassador Mngqikana: Development with Democracy

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is due to visit South Africa in early March, accompanied by a large delegation of officials and entrepreneurs. Thirteen years after the establishment of diplomatic relations between South Africa and Turkey – and twelve years after the opening of the South African Embassy in Ankara – bilateral relations are trouble-free and trade is booming. Diplomat took the opportunity to speak to Ambassador Sobizana Mngqikana. The South African envoy previously studied international relations and represented the African National Congress in London and Stockholm. An accomplished jazz musician, he enjoys a reputation as “the singing ambassador” in privileged Ankara circles. Here he expresses his views both on South Africa’s relations with Turkey and on global issues of particular importance to Africa. The interview was conducted by Bernard Kennedy.

Q How would you sum up the relations between Turkey and South Africa?

A Politically, we have no problems. We support each other on international issues even though Turkey is part of NATO and we are a non-aligned country. Economically, ties are stronger than ever. The volume of trade reached over US$1bn last year, consisting mainly of South African exports, headed by gold. Turkish investments in South Africa have reached US$60m and are still rising following the signing of an agreement on the reciprocal protection of investments in the year 2000. Agreements on economic cooperation and avoidance of double taxation are in the pipeline. We have also agreed to consider a free trade agreement.

Q Are there any respects in which you think relations could be improved?

A There is still a lot of untapped potential. We are eager to see more Turkish investments in South Africa – for example investment in the South African jewellery-manufacturing sector. South Africa is involved in several regional trade and development initiatives, and therefore offers the Turks easy access to the rest of the African continent. I think we are also aware of the opportunity for us to utilise Turkey as a conduit to some of the former Soviet republics. In fact, our Embassy is accredited to five of these republics. There are opportunities for joint ventures in mining and civil engineering in Turkey, Central Asia, Iraq, South Africa and other African countries.

Q What is the Embassy working on at the moment?

A Besides the upcoming visit of Prime Minister Erdoğan, we are very involved in organising participation in trade fairs and in providing information to South African business people. In this way we are trying to overcome the risk-aversion of South African entrepreneurs. Their contacts have been mainly with Western Europe and the Americas in the past, to the neglect of other areas. So it has taken time for us to develop business relations with countries like Turkey, India, Brazil or Southeast Asia – or even with the rest of Africa. I think Turkish businessmen and officials sometimes find it difficult to understand this. But as a matter of policy we are in favour of diversifying our economic relations.

Q Do many Turks visit South Africa for study or leisure purposes?

A There has been a decrease since Turkish Airlines stopped flights to South Africa. We are now hoping to revive direct flights. This will facilitate the movement of people and goods in both directions. South Africa is a good place to study English. It offers the same quality as Europe but much more cheaply. There is no real time difference between South Africa and Turkey, except during the Turkish summer when South Africa is one hour behind Turkey. And of course both countries have a vast tourist potential.

Q Let’s turn to the situation in Africa. What roles is South Africa playing?

A Unfortunately, there isn’t much news about Africa in the Turkish media except when they pick up something negative. Africa does have its own problems, including civil wars. But those are not the only things that are taking place on the Continent. In fact, I think there has been a growth of democratisation in Africa over the past ten years. South Africa has played a leading role here. We have had three democratically conducted elections. This in itself is proof of a stable country. At the same time, we look at democracy not only as a matter of people casting votes but as a process which involves trades unions, non-governmental organisations, interest groups and so on. These organisations may not always agree with the government, and I could give an example of this related to the AIDS issue. But that’s a sign of a dynamic democracy. South Africa also plays a very active role as a peace mediator in certain conflicts in Africa, such as those in Rwanda and Congo.

Q South Africa is also seeking to make an impact on global issues…

A We have an active foreign policy. We are not indifferent. One of our immediate concerns is the shape of international institutions like the UN Security Council, the IMF and the World Bank. We are of the view that some of the forms and policies of these institutions are not relevant to the present century, or do not take account of the transformations that have taken place in the decades since the Second World War. These institutions need to be democratised, to reflect today’s geopolitical and demographic realities. The UN Security Council in particular has been predominantly controlled by a few permanent members. Hopefully with the recommendations that have been presented to the Secretary General there is now going to be greater participation in the decision-making process.

We are also very active in the non-aligned movement. As chairman two years ago, we tried to steer this organisation to a much more pro-active platform. We are not saying that globalisation is wrong per se but we feel that the benefits are distorted in favour of the developed world. African countries, for instance, are unable to find markets for their agricultural products in the western countries. On the contrary, the developed countries are dumping their own excess agricultural products on Africa, thereby undermining the agricultural sector. We are looking forward to a change of attitude. Africa’s dire economic situation is one of the issues, which Prime Minister Blair of the UK is apparently going to raise at the forthcoming G-8 meeting.

Q This would include debt relief?

A There has been a lot of talk about debt relief or cancellation. There are pros and cons. I would like to express a personal view. There has been a campaign to get Iraq’s debt cancelled. In fact, Iraq is a rich country compared to a lot of African countries, which simultaneously have to pay back their debts. To me, it is a contradiction in terms when you have a strong lobby supporting the cancellation of Iraqi debt but you can’t cancel the debts of Togo, which is a poor country.

These are some of the issues, which we find disturbing. So we are trying to develop the South-South dialogue and to lobby organisations like the WTO and the G-8 etc. As developing countries, we do have problems that we can solve as a wider entity or lobby group.

Q Where does the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) fit in?

A This is an African initiative, which has gained general acceptance in the world. We do not want a dependency-type of relationship, based on aid and other forms of economic assistance, which tends to lead the aid-givers to meddle in the internal affairs of the countries concerned. We need to have access to markets. But we accept that, in return for whatever we get, we have got to try to present a democratised society, with regular relations and participation and equality for women. So NEPAD also stands for democratically elected governments rather than military governments.

While we speak with one voice, each country does have its own special concerns. But simultaneously there is a lot of solidarity. South Africa will not only play a leading role but will also share its know-how.

Q Is there also solidarity among the African ambassadors in Ankara?

A Yes, we now have a group of African ambassadors called the African Diplomatic Group. It is still in its infancy. Hopefully we will have a voice. This year we are going to celebrate Africa Day on May 24 on a larger scale than in the past, with seminars, music and similar events.

Q You are now in your fourth and final year in Ankara. What changes have you seen and how has it worked out for you personally?

A The political climate was changing almost daily when I first came, in the wake of the earthquakes and the 2001 economic crisis. After the 2002 elections things became more stable. As for me personally, I found it very easy to acclimatise, but it has been a busy period and there are some things I haven’t found time for. I used to play in a band both in South Africa and London, but now I don’t have time. In future, I look forward to doing more research and reading – I have lost touch with the academic world.

A predilection for blurring the distinction between diplomacy and business is one of the many imputed similarities between Erdogan and former president Turgut Ozal. Many Turkish and Russian enterprises see nothing wrong with that. But 15-20 years of liberalisation have gone by. The later gas pipeline deals with Russia, particularly “Blue Stream”, came to be regarded as scandals in Turkey because of the excessive import obligations, the high prices and the award of contracts without competitive tenders.

According to the global model promoted by the World Bank and the EU – and to which Turkey is committed – infrastructure concessions and privatisation awards (not to mention military purchases) should be undertaken individually by the best bidders – not distributed for some greater good by a paternal prime minister.

In short, although Russia has plenty of energy aces, the trade-offs currently being discussed face serious objections. If some of them nevertheless go ahead, this will be a sure sign of Moscow’s magnetism.

Philately

Centenarian stamps

by Kaya Dorsan

The first Turkish postage stamp went into use during the reign of Ottoman Emperor Sultan Abdülaziz in 1863. Thereafter, new postage stamps were put on sale every 3-4 years.

At that time, there was no tradition of issuing commemorative stamps, and only definitive sets consisting of stamps of various denominations were issued. These stamps bore the portrait of the monarch or some other national symbol or mythological figure. Turkish stamps of the Ottoman period generally displayed the Sultan’s formal signature (tughra), surrounded by a decorative frame.

The Ottoman stamps issued in 1901 had almost run out by 1905, so a new series was put on sale. The stamps thus issued are now exactly a hundred years old.

Domestic mail

The new stamps were headed by a postal series consisting of stamps of ten different values varying from 5 para to 50 kuruş. The stamps bore the tughra of Abdülhamit II.

At the same time, a matbua set of six stamps was issued for use in sending newspapers and printed materials. The word matbua (printed matter) was overprinted on these stamps in Arabic script.

Together with these two sets of postage stamps, a set of two tax stamps was issued. These stamps were printed on red paper and served to charge the receiver of an underpaid item the deficient cost of postage plus a penalty charge.

International competition

Towards the end of 1905, an external set went on sale consisting of four stamps valid only for international despatches. These stamps were overprinted with the letter “B”, which stood for beyiye and indicated that the stamp was to be sold for a price lower than its face value. This was a tactic which enabled the Postal Administration to compete with the foreign post offices which had been permitted to operate in Turkey.

Later, with the abolition of the capitulations, the activities of the foreign post offices in Turkey were prohibited, and the need for the Postal Administration to make such “special offers” disappeared.

Varieties to collect

The 1905 stamps were also used on postal stationeries such as postcards, letter-cards and envelopes. The same stamps were also re-used with fresh overprints several times in subsequent years. As a result, it is possible to build up a large philatelic collection based entirely on the stamp series now exactly a century old.

Speaking Out

Edmond McLoughney: Channelling assistance

After a slow start, assistance is now pouring in from Turkey, as well as from other countries, to the victims of December’s Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. A high proportion of those affected by the disaster were children. Here, Edmond McLoughney, the Representative in Turkey of the United Nations Children’s Fund, explains the role and responsibilities taken on by his organisation. Mr McLoughney has been with UNICEF for 25 years and much of this time has been spent in Africa and the Caribbean. Before coming to Turkey in 2001, he was in charge of the UNICEF programme in Macedonia – a country then trying to cope with an influx of refugees from Kosovo as well as internal problems. We also asked him to comment on the progress being made by UNICEF in its efforts to safeguard the well-being of Turkey’s children. More details of the Fund’s activities in Turkey are profiled opposite.

- Asia: emergency aid

The disaster in southern Asia is something quite extraordinary. Within two weeks, the death toll reached 150,000, and it has continued to rise. Whole communities have been devastated. The local economies – including many heavily reliant on tourism – have been wrecked. Things won’t go straight back to normal. There are so many countless people affected, particularly children. The survivors are in need of material and psychological assistance and will be in need for the foreseeable future.

In the wake of the disaster, a lot of people called the UNICEF Representative Office and the UNICEF National Committee to offer donations. It was a matter of mobilising and channelling this good will. The National Committee has now opened a special bank account and launched a national appeal for funds.

UNICEF has been one of the largest recipients of donations in recent weeks. It has received large amounts from sources as diverse as the Japanese government and Formula-1 driver Michael Schumacher. It is a big responsibility to distribute donations. However, UNICEF has a lot of experience in dealing with both man-made and natural disasters. The organisation originally came into being in the aftermath of the Second World War in Europe as the International Children’s Emergency Fund. Later it turned into a development agency, but there are so many disasters going on around the world, from the Turkish earthquakes of 1999 to the hurricanes in Haiti last September. We were very involved on both those occasions. In practice, a significant part of UNICEF’s annual expenditure goes into disaster relief and recovery.

The funds will be used by UNICEF in four priority areas which UNICEF has identified for children, namely

—survival, which remains a major problem for children in Aceh and elsewhere, particularly in view of the risk of disease;

—separated and orphaned children, who need to be cared for, reunited with extended families where possible and so on;

—protection from opportunists and traffickers, and

–getting children back to school. Many schools have been destroyed, but getting children back in the classroom situation will restore some sense of order to their lives. It’s also a way of identifying those who are particularly affected by trauma. Incidentally, training teachers and others in dealing with trauma was one of the things we focused on here after the 1999 earthquakes. As a result, there are now groups of trained school counsellors in all the high-risk places.

- Turkey:Getting things done

Turkey is fascinating, complex, diverse. It is half-way in the developed world and half-way in the developing world. There are a lot of needs not only in the East and Southeast but also in the cities, where there are a large number of new migrants. These migrants live in much the same conditions as those which prevail in the East and Southeast, and face much the same problems. To give an example, the highest ratio of girls out of school is in Istanbul.

Nevertheless, I really enjoy working here because you can really get things done. I think the proof of that is the rapidly improving indicators of child well-being in the last 5 years or so – particularly lower mortality rates and higher participation in education. Infant mortality fell below 30 per thousand in 2003 compared to 43 in 1998. In this respect, Turkey is well on track towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals which we are working to achieve in conjunction with other UN agencies and with the government, NGOs and other parties.

Our priority project at the moment is called Haydi Kızlar Okula and it’s about persuading parents to send girls to school. Launched in June 2003 in Van by UNICEF Executive Director Carol Bellamy, the campaign aims to equalise enrolment in primary schools.

Education is a basic right. It gives the child a better chance in life. She will not be doomed to suffer another generation of poverty and ignorance. At the same time, there are numerous other arguments for accelerating work on girls’ education. More educated mothers have fewer and healthier children and are healthier themselves. This is shown very clearly in the latest demography and health survey conducted by the Hacettepe University Population Studies Centre. For example, infant mortality rates are three times higher among women who have never been to school that they are among women who have received a secondary level education or higher. And in the EU context, in order to compete, Turkey needs an educated population.

When the campaign was launched in mid-2003, 640,000 more boys than girls were enrolled. Now the gap has been reduced to about 580,000 and the campaign continues. Curiously the campaign seems to be benefiting boys as well as girls.

Another of our campaigns is to promote breastfeeding. Almost all mothers in Turkey breastfeed but not necessarily exclusively. Exclusive breast feeding for the first six months provides the best essential nutrients, the best prospects of brain development – it’s linked to IQ – and the best immunisation and protection against diseases. So we are trying to persuade people not to give baby foods or water or other liquids to their babies in addition to mother’s milk. These are of no extra benefit and they can cause diseases such as diarrhoea, which means that survival may be at stake as well as development. In fact the rate of exclusive breast feeding has doubled in the last five years. We feel we can reach 40% even in the short term.

Turkey is also the only country I can think of offhand which has a national Children’s Day holiday (April 23). This is a national celebration which helps to put children at the top of the agenda and we are very pleased to see that.

UNICEF in Turkey

UNICEF has been present in Turkey since 1951. The Representative, currently Edmond McLoughney, heads up the Turkey country office, which is part of UNICEF’s international organisation. The office employs about 25 people in all. It is responsible for carrying out projects mainly in the areas of child education, health and protection. Current projects related to girls’ education, breastfeeding and street children are examples of such projects. Most of the work is done in conjunction with government agencies and NGOs. “We put a bit of money into accelerating the work,” explains Mr McLoughney, “For example in projects like the girls’ education project we put money into training volunteers to go from house to house, and we pay for associated materials such as the guide book for volunteers. On the other hand, more schools are needed and we don’t pay for more schools – we think that’s the government’s job.”

The UNICEF office also lobbies the government for the adoption of policies and legislation needed to protect children. It has contributed to the adoption of legislation on iodized salt to prevent goitre and other iodine deficiency disorders. In addition, the office runs a website (www.unicef.org/Turkey) and a newsletter, in order to try to highlight the problems which children are facing in Turkey, the opportunities available for tackling these problems and the successes achieved. It contributes to, and distributes, UNICEF’s flagship annual report The State of the World’s Children, published at the end of each year.

National Committee

As a country spanning the rich and poor worlds, Turkey does not only receive assistance from UNICEF; it is also a source of funds for the organisation’s activities. The UNICEF Turkish National Committee is one of about thirty national committees which exist in the industrialised countries. These committees are NGOs with an affiliation with UNICEF and they are involved in fund-raising. About a quarter of UNICEF’s funding globally comes from the public through the various national committees.

The current president of the National Committee is Professor Talat Halman of Bilkent University, a former minister of culture. The honorary president is Professor İhsan Doğramacı, the paediatrician and former president of the Higher Education Council. It was Professor Doğramacı who first established the Committee. Funds are raised for the organisation in general and also for specific projects such as the current campaign to ensure that girls are enrolled in primary education.

World View

The “Palestine Question” Reconsidered

by Prof. Dr. Türkkaya ATAÖV

The unceasing and sanguinary conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is causing appalling agony in the conscience of world public opinion as well as in the everyday lives of the two feuding parties. Rationale and sensibility require a conclusive terminus to slaughter that not only brings anguish to families but also brutalizes societies. There have been recurring alienation, endless enmity, repetitive wars and accompanying calamities such as humiliation, expulsion, displacement and loss of lives. This tragedy, lasting about six decades, is an unbearable burden on the moral sense of all with sentiment and judgement. Plainly, this cannot go on. Now finding ourselves over the threshold of the 21st century, we should expound and argue persuasively that this state of affairs needs to be changed.

We Turks are understandably sensitive over the volatile controversy. We share common borders, exquisite culture and peaceful objectives with our Arab neighbours. We always had excellent relations with world Jewry. We take pride for having opened our land to them, principally during the European Inquisition of the late 15th century, and again before and after the Nazi Holocaust. Our behaviour in both cases was much more than accommodating and bestows on us well-earned dignity and ethical grandeur.

It is no coincidence that no blood was shed between the Arabs and Jews during the long Ottoman centuries in that ancient land of Pale stine. These two communities and others were separately represented in both the Ottoman parliaments of 1876 and 1908. The peaceful coexistence then is proof that they can live together in harmony, under different circumstances, within the boundaries of a larger state.

Remembering the past

Turkey indeed enjoys a special standing between the Palestinians and the Jews. It is only consistent with the Turkish past that this country’s foreign minister, Abdullah Gül, paid his respects at Yad Vashen. The most famous Holocaust museum in the world, it was created in 1953 to commemorate the memory of close to six million Jewish victims. Situated on the former Arab land of Ein Kerem, on what has been renamed the “Mount of Remembrance” (Har Ha’Zikaron), Yad Vashen is a huge, sprawling complex of tree-studded walkways intermingled with museums, memorials, monuments, archives and sculptures. The museum was expanded in1963 to honour “Righteous Gentiles” – non-Jewish persons who risked their lives, freedom or safety, without expecting any monetary compensation, in order to rescue Jews from death or deportation. We are again proud that the names of a number of Turks appear there.

The name of the former King Muhammed V of Morocco should have been added to the above list as well. He refused to surrender the Jews of his country to the fascists, stating courageously and in the full consciousness of patriotism that he had “only Moroccan citizens”.

We shall have a much more peaceful world if we implant in our minds that victimhood does not belong to only one side only (The same truth applies to the history of Turkish Armenian relations). Only 1,400 meters to the north of Yad Vashem lie the remains of the Palestinian victims of Deir Yassin. What occurred in Deir Yassin on April 9, 1948 (or in various other places) may be found not only in the columns of the New York Times of April 10 and 13, but also in the statements of the Irgun and Stern commanders of those days.

Looking forward

Our eyes are, nevertheless, set on the future. About 200 writers, professors, journalists and other intellectuals recently came together at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland to discuss ways and means that might be employed to attain a bloodless and tranquil morrow. Participants included prominent individuals from Israel, Palestine and other Arab countries as well as experts from as far afield as Canada and Australia, Russia and South Africa. Foremost among the proposals under discussion was the idea of “one democratic and secular state in Israel/Palestine”.

Such options are not entirely new. Distinguished Jewish intellectuals like Arendt, Benvenisti, Berger, Buber, Ellis, Herskovitz, Klepfisz, Magnes, Menihuin, Rubenberg, Tsemel and others emphasised Jewish-Arab cooperation and unity in the past. Outstanding names on the Arab side are Edward Said, Naim Khader, Ghassan Tueni and others. I would also like to recall that Muammer Al-Khaddafi published a small book, entitled Isratin, available in several languages. The latter is a timely treatise drawing attention to a repressed option that looks, at first glance, less practical bur more virtuous

Just and enduring peace is possible. It was the order of the day during the 400 years of Otoman presence. Of course, many things have occurred since then. But one has to start on the road to mutual tolerance some time. As Rami Adwan, a Palestinian from North Gaza, proposed at the Lausanne Conference, a people-to-people program for Arabs and Israelis should be adopted as a system of educating the public in the virtues of peaceful coexistence. The “Cultural Coffee Shop” experience in East Jerusalem is an initiative worth expanding. Peace is not an illusion; it can be achieved with human effort. Many realities of our day were the utopic visions of the past.

The author is Professor Emeritus in International Relations at Ankara University. He is acknowledged worldwide as an outstanding analyst of the Palestine question. His numerous books and articles have appeared in twenty languages. He participated at the Lausanne University Conference, quoted in this article, and is currently preparing a book in the English language, which is to be published in Europe.

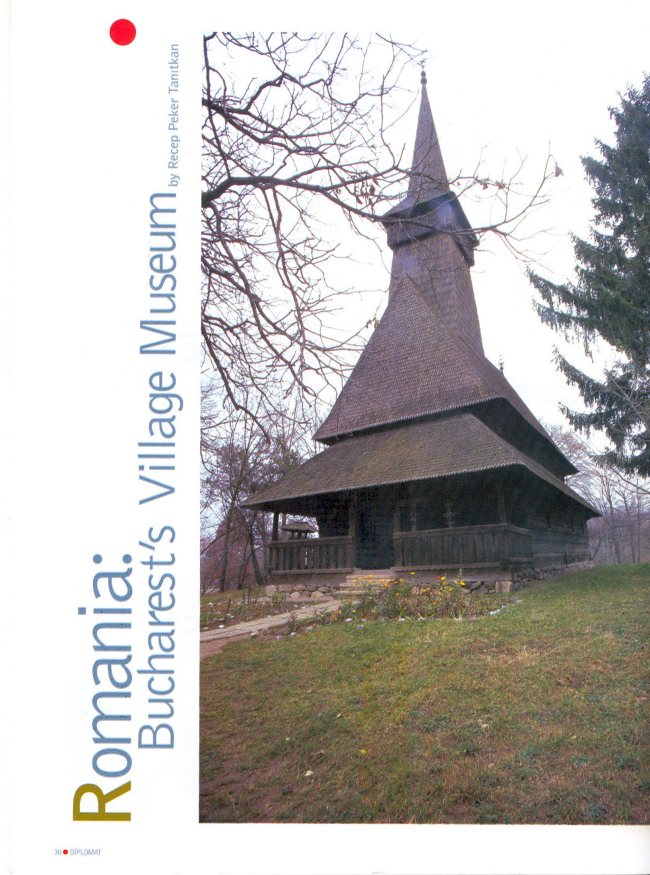

Romania: Bucharest’s Village Museum

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

An extraordinary life-size village in the heart of Bucharest graphically displays the country’s rural past. At the same time, the Village Museum’s own history reflects the intellectual, cultural, political and commercial changes of the past eighty years.

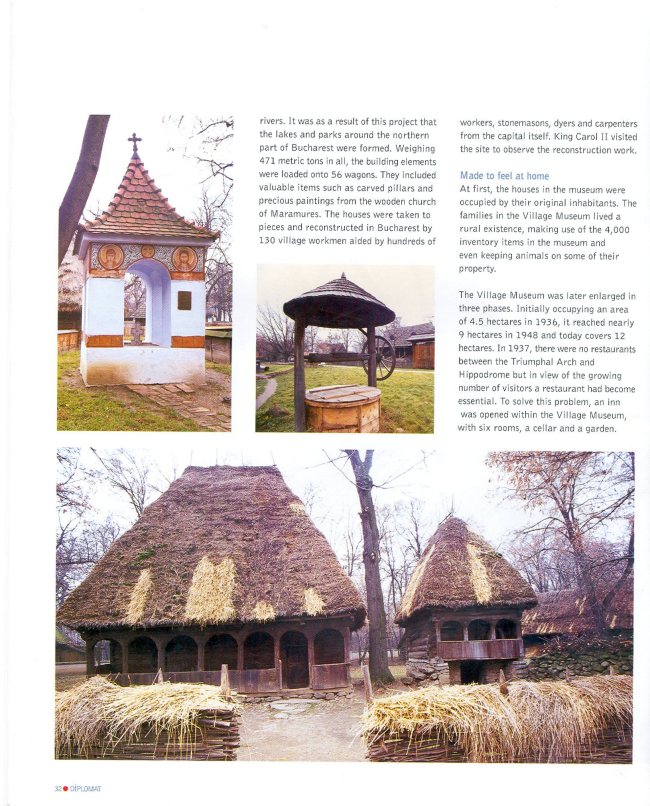

In the heart of Bucharest, Romania, stands an entire rural village – 322 buildings in all including 47 houses, outhouses, windmills and wooden churches. These are not fakes or reproductions but real houses with real working agricultural equipment, dismantled and put together again by authentic village workmen. It is the ultimate open-air museum – a curiosity, perhaps, but also a testament to the ethnographical research of a by-gone era.

It all began in 1925 when a group of ten sociology students under Professor Dimitrie Gusti headed for the village of Goicea Mare in the Oltenia region (Gorj province) carrying forms bearing titles such as “cosmological dimension”, “biological dimension”, “historical dimension” and “psychological dimension”. Starting from sample villages, the aim was to generate an accurate sociological map of the entire nation. This may not have been achieved, but the experience and articles produced certainly helped to draw international attention to the Romanian sociology school.

Grand scale

The research took on new dimensions in 1936, when the sample houses were dismantled and brought to Bucharest. The houses displayed traditional features not only from the villages but also from other settlements, indicating that the study was intended to cover the whole of Romania.

In 1932, efforts had got under way to change the courses of the Colentina and Mostistea rivers. It was as a result of this project that the lakes and parks around the northern part of Bucharest were formed. Weighing 471 metric tons in all, the building elements were loaded onto 56 wagons. They included valuable items such as carved pillars and precious paintings from the wooden church of Maramures. The houses were taken to pieces and reconstructed in Bucharest by 130 village workmen aided by hundreds of workers, stonemasons, dyers and carpenters from the capital itself. King Carol II visited the site to observe the reconstruction work.

Made to feel at home

At first, the houses in the museum were occupied by their original inhabitants. The families in the Village Museum lived a rural existence, making use of the 4,000 inventory items in the museum and even keeping animals on some of their property.

The Village Museum was later enlarged in three phases. Initially occupying an area of 4.5 hectares in 1936, it reached nearly 9 hectares in 1948 and today covers 12 hectares. In 1937, there were no restaurants between the Triumphal Arch and Hippodrome but in view of the growing number of visitors a restaurant had become essential. To solve this problem, an inn was opened within the Village Museum, with six rooms, a cellar and a garden.

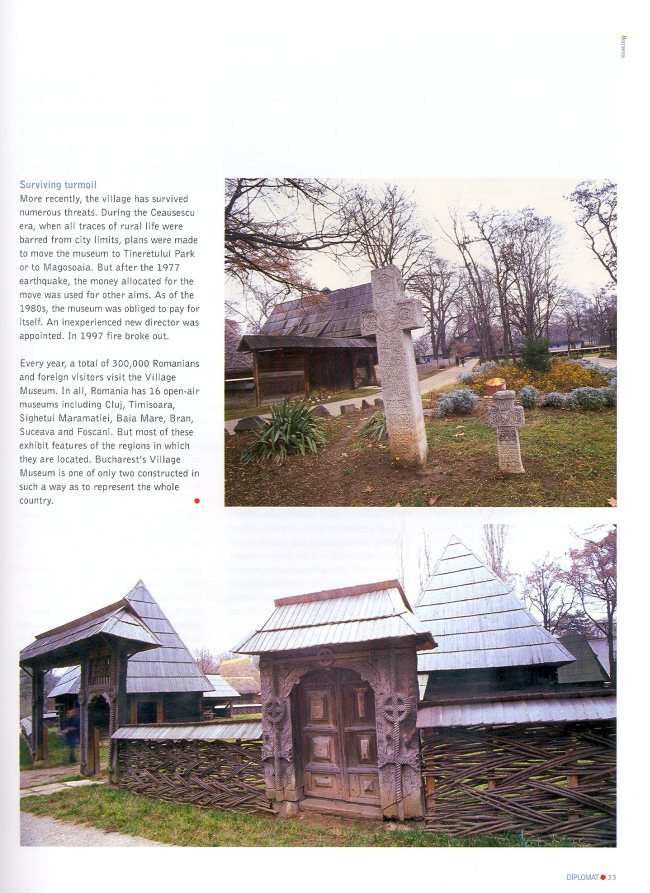

Surviving turmoil

More recently, the village has survived numerous threats. During the Ceausescu era, when all traces of rural life were barred from city limits, plans were made to move the museum to Tineretului Park or to Magosoaia. But after the 1977 earthquake, the money allocated for the move was used for other aims. As of the 1980s, the museum was obliged to pay for itself. An inexperienced new director was appointed. In 1997 fire broke out.

Every year, a total of 300,000 Romanians and foreign visitors visit the Village Museum. In all, Romania has 16 open-air museums including Cluj, Timisoara, Sighetul Maramatiei, Baia Mare, Bran, Suceava and Foscani. But most of these exhibit features of the regions in which they are located. Bucharest’s Village Museum is one of only two constructed in such a way as to represent the whole country.

Antiques

The treasures of Gamze Ulusoy

by Sibel Dorsan

No amount of functionality or minimalism can quench the urge to acquire rare objects imbued with the tastes, skills and dramas of past generations. Born collector Gamze Ulusoy is helping to keep the passion alive in an Ankara antique shop which makes her customers – or visitors – feel very much at home. She also offers some tangible advice.

The term “antiques” is generally used to designate works of art and other objects of historical value which are at least 100-150 years old. But it is not just age or history that qualifies an object for the epithet “antique”. At the same time, the item must be aesthetically pleasing, and reflect the crafts or tastes of a given era. It has to be well preserved, and capable of carrying out the same function which it performed in the past. And it should be sufficiently rare that it is possible to estimate the number of surviving examples.

The collection of such objects is almost as old as the history of human existence. It can be said to begin with the storage of treasure in temples. In the United Kingdom, where antiques are highly regarded not only for their aesthetic values but also for their historical importance, artefacts illustrating the history of the country have been collectors’ items ever since the 16th century. The museums containing the most renowned antique collections opened in London in 1857, in Vienna in 1863, in Paris in 1882 and in New York in 1897. In the twentieth century, the collection of antiques gained widespread popularity well beyond the confines of these cities. And if anybody thinks modern Ankara is an unlikely place for the pursuit of this passion, they have yet to visit Gamze Ulusoy’s Tahran Caddesi shop.

Early start

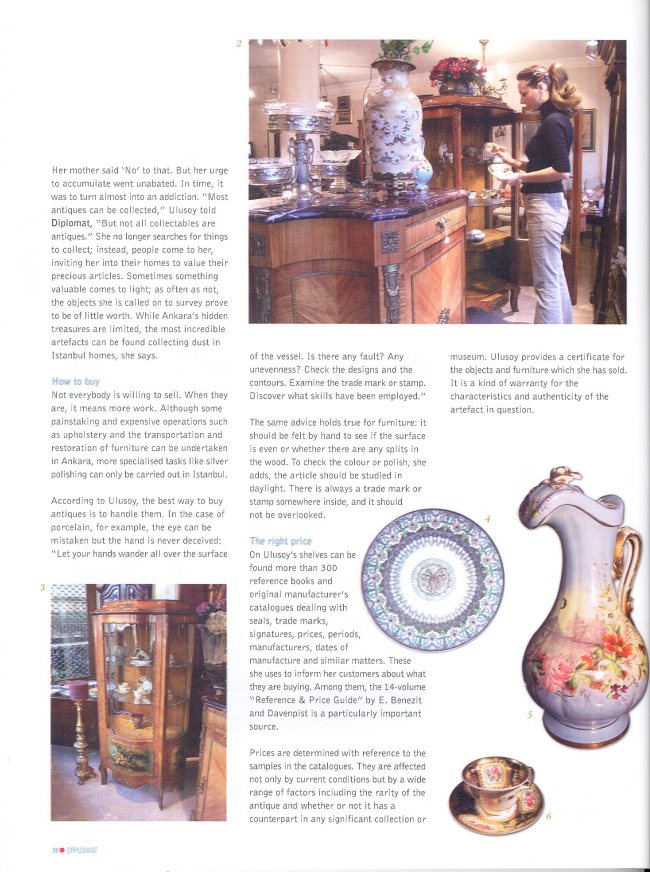

The interior looks not so much like a shop where antiques are sold, as like a house which happens to be full of them. Collecting runs in Ulusoy’s veins. Every time she went to the Citadel as a child, she would buy some object or other with her pocket money and add it to her modest collection. As a middle school student in the 1980s, she proposed to buy a series of four small Yalçın Gökçebağ paintings depicting the four seasons, which she came across at a joint exhibition at the Mi-Ge Gallery owned by her aunt. These were to adorn her bedroom. Her mother said ‘No’ to that. But her urge to accumulate went unabated. In time, it was to turn almost into an addiction.

“Most antiques can be collected,” Ulusoy told Diplomat, “But not all collectables are antiques.” She no longer searches for things to collect; instead, people come to her, inviting her into their homes to value their precious articles. Sometimes something valuable comes to light; as often as not, the objects she is called on to survey prove to be of little worth. While Ankara’s hidden treasures are limited, the most incredible artefacts can be found collecting dust in Istanbul homes, she says.

How to buy

Not everybody is willing to sell. When they are, it means more work. Although some painstaking and expensive operations such as upholstery and the transportation and restoration of furniture can be undertaken in Ankara, more specialised tasks like silver polishing can only be carried out in Istanbul.

According to Ulusoy, the best way to buy antiques is to handle them. In the case of porcelain, for example, the eye can be mistaken but the hand is never deceived: “Let your hands wander all over the surface of the vessel. Is there any fault? Any unevenness? Check the designs and the contours. Examine the trade mark or stamp. Discover what skills have been employed.”

The same advice holds true for furniture: it should be felt by hand to see if the surface is even or whether there are any splits in the wood. To check the colour or polish, she adds, the article should be studied in daylight. There is always a trade mark or stamp somewhere inside, and it should not be overlooked.

The right price

On Ulusoy’s shelves can be found more than 300 reference books and original manufacturer’s catalogues dealing with seals, trade marks, signatures, prices, periods, manufacturers, dates of manufacture and similar matters. These she uses to inform her customers about what they are buying. Among them, the 14-volume “Reference & Price Guide” by E. Benezit and Davenpist is a particularly important source.

Prices are determined with reference to the samples in the catalogues. They are affected not only by current conditions but by a wide range of factors including the rarity of the antique and whether or not it has a counterpart in any significant collection or museum. Ulusoy provides a certificate for the objects and furniture which she has sold. It is a kind of warranty for the characteristics and authenticity of the artefact in question.

Taking care

The maintenance of antiques requires great care. Porcelain and glass should be washed with white soap in a bowl lined with a towel, says Ulusoy, while contours can be cleaned with an old toothbrush. She suggests that furniture should initially be dusted with a dry cloth, then polished with the appropriate specialist products. A wet cloth should never be used.

Have today’s minimalist design trends reduced the attraction of antiques? Gamze Ulusoy will not hear of it. On the contrary, she believes that the proliferation of similar designs incites the yearning to be different – and hence to acquire things with a character of their own. The magnificence and romanticism of antique objects cannot be denied. “The idea of antiques is as old as human history. How can it simply disappear?”

Ankara Station: Keeping up appearances

by Bernard KENNEDY

If buildings could speak, they would all have tales to tell. Ankara’s nostalgic railway station has seen more ups and downs than most Long deprived of the central role which it once enjoyed in the economic and social life of a young nation, it continues to ply its trade, thankful for all the custom it gets.

Cigarettes and embraces come to an end. A last door slams. The coaches start to shuffle down the broad, low marble platform counting off rows of green ironwork. Neither rushed nor delayed, a lunchtime train heads for Istanbul or the East. In the wake of silence, a passing clerk requests a sandwich from the fortress-like “büvet”. Under the 12-metre ceiling of the central hall, newspapers open again. Daylight floods in through the tall, double glass doors on simple city and country faces surrounded by solid marble, polished wood and shining brass.

There will be more arrivals and departures when dark falls – Istanbul, Izmir, Kars, Diyarbakir, Zonguldak and, as it is Thursday, Tehran. Yet despite their names – the Anatolian Express, the Bosphorus Express, the Çukurova Express, the Black Diamond Express – all will take long hours to reach their destinations. Seats are available on all.

Stylish setting

Ankara’s one-sided stone-clad railway station centres on a grand six-columned neo-classical portal flanked by rounded staircase “towers” and topped by the metallic emblems of the State Railways (TCDD). Ever-lower, ever-receding blocks to left and right, their horizontal lines emphasised, defer in perfect symmetry to this monumental centrepiece.

Such was the stylish setting deemed appropriate, in the second decade of the Republic, for the primary gateway to a new capital city. Once a social main line, however, the station has since been shunted with all its period embellishments to the sidings of urban life.

Strategic value

The railway had arrived in Ankara in 1892, an extension of the Istanbul-Izmit line and a branch of the Ottoman-Deutsche Bank “Baghdad Railway” project. Strategically it reinforced Ankara’s ancient staging post role; socially it drew the town closer to modern trends and ideas. Thus the unsuspecting province was prepared for its later role as capital. For administrative purposes, a house called the Direksiyon was constructed next to the original two-storey station. And it was from here that Ataturk coordinated most of the War of Independence.

The early Republic needed no convincing of the importance of rail, unifying the existing networks and doubling the length of track. Resuming its eastward march, the Ankara line reached Kayseri in 1927, Sivas in 1930 and Erzurum in 1939. Meanwhile, the twisting carriage-way that traversed the swamp between the Ankara station and the city centre at Ulus became a straight-backed, tree-lined boulevard. On an adjacent plot rose a new six-floor TCDD headquarters designed by Mimar Kemalettin, leading protagonist of the “first national architecture movement”.

Rising classes

Kemalettin’s HQ – later to become a training centre for railway staff – was completed in 1930, three years after the death of its architect. Arranged around a courtyard, it incorporated decorative elements of Ottoman public and vernacular architecture, In contrast, the new station, designed by 25 year-old Şekip Akalın and opened in 1937, was fiercely international.

A gazino or music hall was built simultaneously, surrounded with parkland and linked to the station by a colonnaded walkway. While the formal station restaurant became a meeting place for politicians and high-ranking bureaucrats, the Gar Gazinoso, with its 32-metre clock tower and upper storey viewing terrace, played host to foreign orchestras and revues. A night out to remember for Ankara’s eagerly-westernising upper and middle classes!

Roads and motorways

Within a generation, social norms and habits changed. High society migrated to the south of the city, the railways were neglected, new roads were built and bus companies mushroomed. Until the 1980s, the slow-but-comfortable Blue Train or sleeper remained a privileged means of travelling between Istanbul and Ankara. But then came the motorway, the explosion in car ownership and the increase in air traffic. Symbolically, the Transport Ministry abandoned its powerful 1941 edifice beyond the station for an Eskişehir Road location.

The gazino served briefly as a Turkish Airlines office and terminal but now stands empty and shrunken. Across the wide station forecourt, Kemalettin’s light facades have largely stood the test of time, but relegated to the status of a regional directorate they await an uncertain fate. The station itself lives on: tickets are still sold behind the time-worn marble turnstiles; the waiting room still fills, and the restaurant still serves. But little business is done in the post office and barber’s shop, while dust gathers in the baggage hall and behind the left luggage windows.

Praying for a future

The Direksiyon Building, with its Atatürk mementos, is carefully preserved as a museum, its roof respectfully accommodated by the canopy of Platform One. Turn back and you come to the TCDD Museum and Art Gallery. On a separate site across the distant commuter tracks is an open air exhibit of steam engines. The VIP lounge is a museum too, in all but name.

Outside the first TCDD headquarters, sharing a garden with an empty pool and a retired locomotive, grows a twisted yet muscular blue fir, rivalling the building for both age and height. With the pacing gendarmes it has guarded Ankara’s station through thick and thin. The wind has brought news of high-speed trains which might halve the journey time to Istanbul and restore the supremacy of rail. And the tree prays to live to see the day when its humbled protégé is back at the heart of things.

Lake Yeniçağa: Red skies and birdsong

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

Just minutes from the autobahn lies a beauty spot disturbed only by the whir of wings and the quacking of ducks. The discerning visitor is up and about before the sun rises and does not leave before it sets.

If you listen carefully as you approach the Bolu junction on the Istanbul-Ankara road, your ear may catch the gentle rhythm of the ripples of Lake Yeniçağa inviting you to drop by. At close hand, the lake is equally enchanting – and most of all at daybreak, when the first rays of light struggle to pierce the mists which rise above the water, and to pick out the silent anglers dotted round the shore. Fınally the sun appears, a full-formed ball of fire, awakening green fields which flood with poppies and daisies every Spring

Together with its ideal bungalows and picnic spots, the lake occupies a shallow basin some 40 kilometres from the city, at an altitude of about 1,000 metres. The anglers are rarely disappointed. Twelve metres deep in places, the waters harbour a range of aquatic life forms from crayfish to mirror carp. Specimens of up to 20 kilograms have reputedly been caught.

Magic moments

Dozens of species of birds find shelter and sustenance in the surrounding brooks and deltas. In one breathtaking moment a whole flock will take wing from the water and begin to circle the lake in impeccable formation. It is a precious sight – a feast for the eyes of angler and passer-by alike. Among the reeds, the ducks and ducklings call to one another – a symphony by dawn; a lullaby at dusk.

Sunset is no less spectacular, and there can be few simpler or less ambiguous pleasures than to watch the surface of the lake blaze orange and flush crimson as the sun sinks slowly over the mountain-tops while partaking of a hearty meal at the modest lakeside restaurant.

Awaiting visitors

In addition to angling and water sports, the lake and its environs are an ideal walking zone, known as Route 19 to activity holiday planners. Situated just off the international D-100 highway and the TEM motorway, the area is easily accessible at all times and from all directions. Ömer Sayın, mayor of the district centre of Yenicaga, has already enhanced the lakeside with recreation sites, and now plans to attract more visitors by increasing the available accommodation.

Clash of bards

In July, Yenicaga commemorates its local bard, Poet Dertli, with celebrations which include a contest among latter-day minstrels. In the village of Eskiçağa, the oldest settlement of the district, stand a mosque, a hamam and a shrine thought to have been built during the reign of the fourth Ottoman sultan, Yıldırım Beyazıt.

Olive Oil: Liquid gold of the Aegean

by Recep Peker Tanıtkan

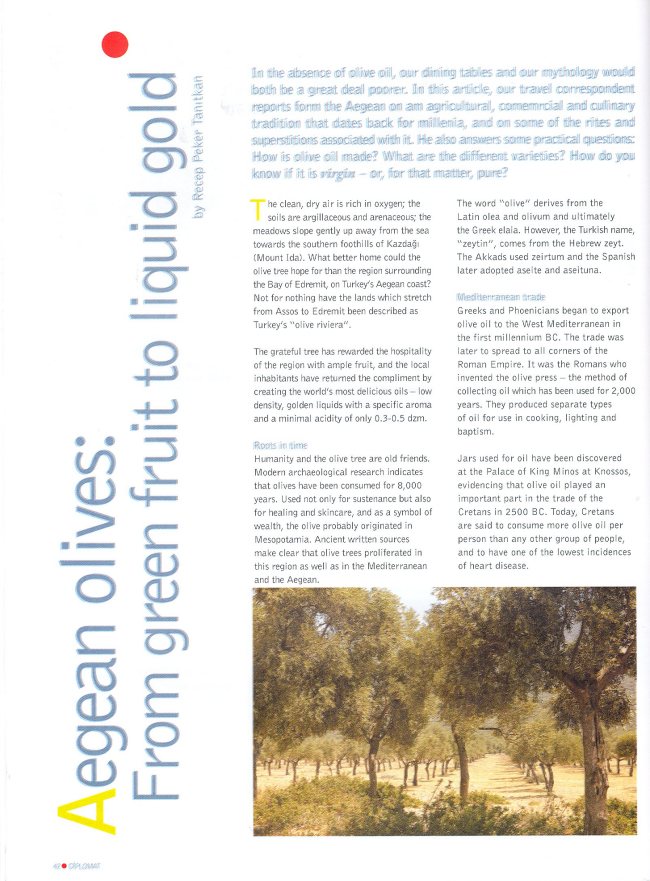

In the absence of olive oil, our dining tables and our mythology would both be a great deal poorer. In this article, our travel correspondent reports form the Aegean on am agricultural, comemrcial and culinary tradition that dates back for millenia, and on some of the rites and superstitions associated with it. He also answers some practical questions: How is olive oil made? What are the different varieties? How do you know if it is virgin – or, for that matter, pure?

The clean, dry air is rich in oxygen; the soils are argillaceous and arenaceous; the meadows slope gently up away from the sea towards the southern foothills of Kazdağı (Mount Ida). What better home could the olive tree hope for than the region surrounding the Bay of Edremit, on Turkey’s Aegean coast? Not for nothing have the lands which stretch from Assos to Edremit been described as Turkey’s “olive riviera”.

The grateful tree has rewarded the hospitality of the region with ample fruit, and the local inhabitants have returned the compliment by creating the world’s most delicious oils – low density, golden liquids with a specific aroma and a minimal acidity of only 0.3-0.5 dzm.

Roots in time

Humanity and the olive tree are old friends. Modern archaeological research indicates that olives have been consumed for 8,000 years. Used not only for sustenance but also for healing and skincare, and as a symbol of wealth, the olive probably originated in Mesopotamia. Ancient written sources make clear that olive trees proliferated in this region as well as in the Mediterranean and the Aegean.

The word “olive” derives from the Latin olea and olivum and ultimately the Greek elaia. However, the Turkish name, “zeytin”, comes from the Hebrew zeyt. The Akkads used zeirtum and the Spanish later adopted aseite and aseituna.

Mediterranean trade

Greeks and Phoenicians began to export olive oil to the West Mediterranean in the first millennium BC. The trade was later to spread to all corners of the Roman Empire. It was the Romans who invented the olive press – the method of collecting oil which has been used for 2,000 years. They produced separate types of oil for use in cooking, lighting and baptism.

Jugs used for oil have been discovered at the Palace of King Minos at Knossos, evidencing that olive oil played an important part in the trade of the Cretans in 2500 BC. Today, Cretans are said to consume more olive oil per person than any other group of people, and to have one of the lowest incidences of heart disease.

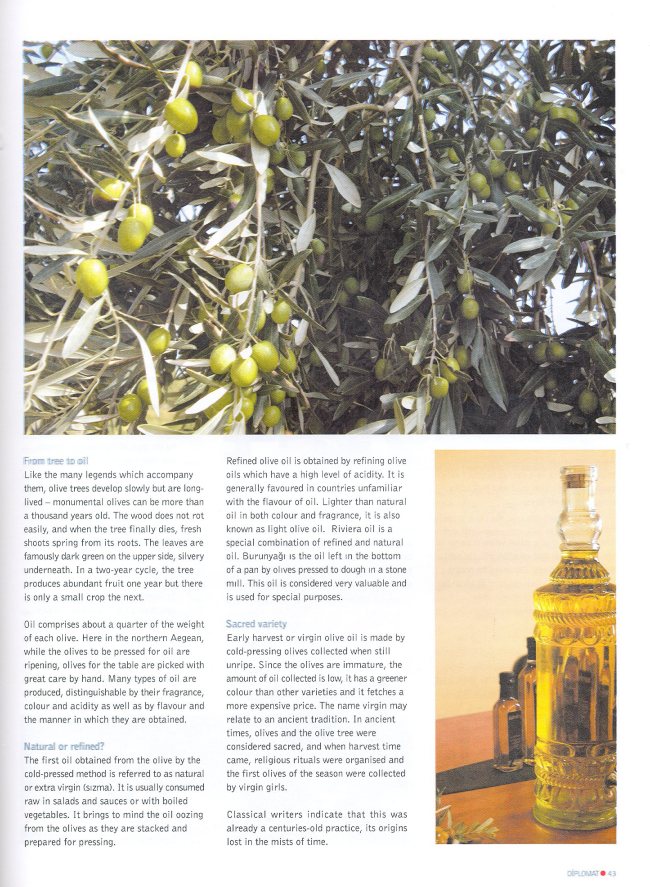

From tree to oil

Like the many legends which accompany them, olive trees develop slowly but are long-lived – monumental olives can be more than a thousand years old. The wood does not rot easily, and when the tree finally dies, fresh shoots spring from its roots. The leaves are famously dark green on the upper side, silvery underneath. In a two-year cycle, the tree produces abundant fruit one year but there is only a small crop the next.

Oil comprises about a quarter of the weight of each olive. Here in the northern Aegean, while the olives to be pressed for oil are ripening, olives for the table are picked with great care by hand. Many types of oil are produced, distinguishable by their fragrance, colour and acidity as well as by flavour and the manner in which they are obtained.

Natural or refined?

The first oil obtained from the olive by the cold-pressed method is referred to as natural or extra virgin (sızma). It is usually consumed raw in salads and sauces or with boiled vegetables. It brings to mind the oil oozing from the olives as they are stacked and prepared for pressing.

Refined olive oil is obtained by refining olive oils which have a high level of acidity. It is generally favoured in countries unfamiliar with the flavour of oil. Lighter than natural oil in both colour and fragrance, it is also known as light olive oil. Riviera oil is a special combination of refined and natural oil. Burunyağı ıs the oil left ın the bottom of a pan by olıves pressed to dough ın a stone mıll. This oil is considered very valuable and is used for special purposes.

Sacred variety

Early harvest or virgin olive oil is made by cold-pressing olives collected when still unripe. Since the olives are immature, the amount of oil collected is low, it has a greener colour than other varieties and it fetches a more expensive price. The name virgin may relate to an ancient tradition. In ancient times, olives and the olive tree were considered sacred, and when harvest time came, religious rituals were organised and the first olives of the season were collected by virgin girls.

Classical writers indicate that this was already a centuries-old practice, its origins lost in the mists of time. According to some the ancient Greeks regarded olives as a sacred product which could only be cultivated and picked by virgin girls and boys.

Ideal oil

The ancients had a point when it came to the divine qualities of olive oil. Its uses are almost endless. Contrary to recent belief, olive oil of all types of is ideal for frying, since it burns at a higher temperature than other culinary oils. Easily digested, olive oil can also be flavoured with garlic, onion, basil, coconut seed, rosemary, thyme, peppers or bay leafs, adding to the appeal and variety of the salads, appetizers and meals in which it is used.

A good olive oil obtained by traditional methods can leave a slight sediment at the bottom. It may turn cloudy if chilled – indeed, one way of testing the purity of the oil is pure is to put it in a refrigerator, where it should freeze. Normally, it is best to keep olive oil at room temperature but in a dark place. That is what the people of Edremit tell you – and they should know.

Shrouded in legend

Most people have heard the story of the dove which returned to Noah’s boat with an olive leaf in its beak, proving that the waters had started to recede after the flood – and making the olive branch a symbol of peace. But this is only one of the many tales about olives to be discovered in ancient literature and legend:

- According to one story, the dying Adam beseeched God for the oil of mercy. Upon Adam’s death, his son took three seeds from the tree of good and evil which grew in the Garden of Eden and placed them in his father’s mouth. When his father was buried, the seeds sprouted, and the olive, the cedar and the cypress grew from them.

- Athena, the founder and protector of the city of Athens, defeated Poseidon in a contest adjudicated by the gods of Olympus by offering the olive tree as a gift to humanity – the gods found the tree more beneficial than Poseidon’s gift of a horse.

- The ancient Egyptians were ostensibly taught to cultivate the olive tree and obtain olive oil by the goddess Isis.

- In Roman tradition, too, the tree was donated by a goddess – in this case, Minerva.

- The legendary founders of the city of Rome, Romulus and Remus, were born under an olive tree.

- According to the Torah, Jehovah told Moses how to prepare baptism oil using olive oil and various odours.

- The olive tree is also referred to in the Koran: it is stated that the tree came from Mount Sinai, and that oil is obtained from its fruit and used for enriching meals.